A major storm might not necessarily be good news, but for a group of researchers in New Zealand, bad weather has uncovered a set of 1-million-year-old footprints on a beach. Thought to have been left by a moa, an ancient, now extinct, flightless bird, the footprints have helped scientists learn more about their ecology, behavior, and potentially even revealed a new species.

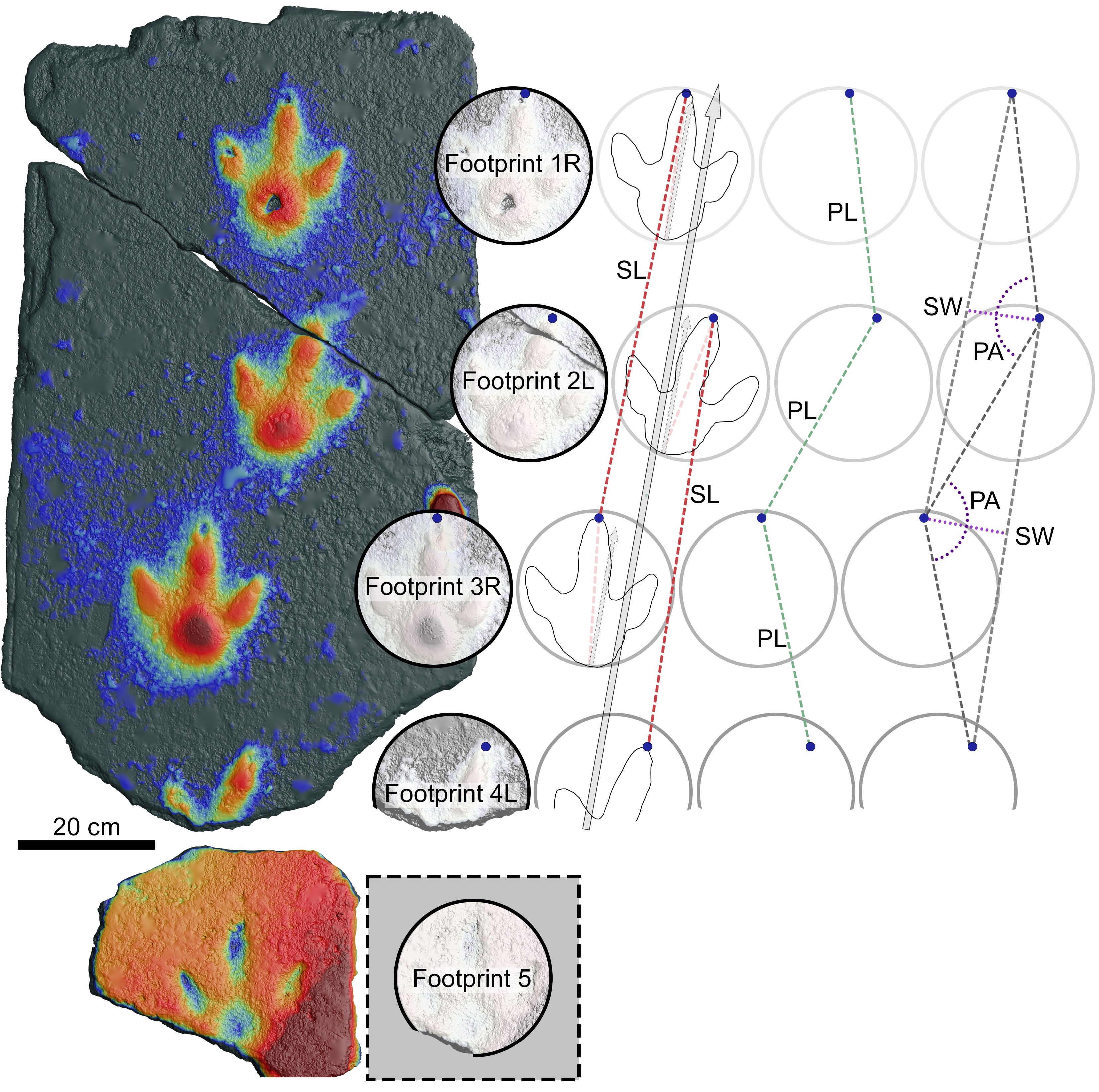

The trackway was discovered at Manunutahi (Mosquito Bay) in the Kaipara region of New Zealand’s North Island in March 2022 and contained “four positive relief footprint casts and a single negative relief footprint impression,” explain the authors in the study describing their findings.

Through scientific analysis of the footprints and the gait, the team determined that the bird would have been roughly 80 centimeters (2.6 feet) tall at the hip and weighed around 29 kilograms (64 pounds). The researchers could also work out the walking speed of the moa, finding that it was only traveling at 1.7 kilometers per hour (1.1 miles per hour), slower than human adults, ostriches, and emus, suggesting it was simply enjoying a leisurely stroll on the beach.

The team further estimated that the footprints were made in the Early to Middle Pleistocene, potentially making them up to around a million years old, give or take half a million years.

“The age of the footprints was determined by studying the grain size, grain composition and stratigraphic relationships of the sediments they had been made in to identify the ‘host sedimentary unit’, which is Karioitahi Group sandstone. With this identification made, the host sediment could be correlated to other parts of Karioitahi Group sandstone that had previously been dated,” Dr Daniel Thomas – Honorary Academic, School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland and Research Associate, Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira – explained to IFLScience.

The team was helped by Māori knowledge and culture in the process of understanding these footprints. Humans and moas would have lived alongside each other: “kōrero tuku iho (tradition) confirms ancestral knowledge of and direct experiences, to about the end of the seventeenth Century, with moa – locally in south Kaipara also referred to as kura(nui) and te manu pouturu (the bird on stilts)” explain the authors. Though these footprints would have predated the arrival of humans to Aotearoa, it’s possible the bird’s descendants lived alongside them.

To remove the trackway from the beach was no easy feat; battling tide times, the team worked hard to remove the sandstone safely for their analysis. “We knew that the odds were against us, as the sandstone slab was extremely soft and friable, but we all agreed it was worth a shot,” said Ricky-Lee Erickson, Collection Manager, Land Vertebrates at Auckland Museum, in a statement seen by IFLScience.

“On the day of the excavation, we met at high tide, and waited for the water to retreat enough to get started. The team worked to carve off excess sandstone from the block and a support structure was rigged up to carry the prints. As the tide rapidly approached, the sandstone block was placed on a ute trailer and driven off the beach just as the water started to creep towards the tyres.”

Footprint 5 was discovered 30 centimeters (11.8 inches) away from the main group.

After the removal of the trackway, a karakia (a Māori cultural practice) was held to welcome the footprints. They have been housed at the Ngā Maunga Whakahii o Kaipara facility for the last two years. “The footprints remain in the care of Ngā Maunga Whakahii o Kaipara (the post-settlement entity for Ngāti Whātua o Kaipara – mana whenua and kaitiaki of the area). Preserving this taonga within the rohe ensures the footprints are directly accessible to mana whenua and can be used for education, research, and maintain the connection to whakapapa and whenua,” explains a statement seen by IFLScience.

Interestingly, there are nine known species of moa that once roamed New Zealand, but when looking closely at the footprints, the team had a difficult time assigning which of these species would have made the trackway. Instead, they think it is possible that the footprints were made by a different, unknown species.

“We discovered a mismatch between the width of the ankle region of the footprints and the widths of the ankle bones (i.e., tarsometatarsi) of the moa species that were known to be living in Aotearoa New Zealand when people first arrived. The ankle bones we were studying were either much too large or much too small to have been the Kaipara trackmaker,” Thomas told IFLScience.

One suggestion is that the tracks were made by a subadult; moa species like the North Island giant moa (Dinornis novaezealandiae) could reach heights between 2 to 3 meters (6.6 to 9.8 feet), so it’s possible that the tracks were made by a juvenile. “Perhaps this was a subadult of a giant species. Other possibilities include that this was a previously unrecognized species, or that this was one of the species that we do know about, but it was showing much greater variation in foot shape than previously recognised,” said Thomas.

The study is published in the New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics.

Source Link: 1-Million-Year-Old Ancient Moa Footprints From New Zealand Are Unlike Any We've Seen Before