Prehistoric ornaments made of stone and volcanic glass provide the earliest conclusive evidence for body piercing ever discovered. Recovered from graves at a Neolithic settlement in Türkiye, the 11,000-year-old accessories are likely to have been associated with coming-of-age rituals in which young adults were pierced in order to symbolize their passage from childhood to maturity.

Previous findings have hinted at decorative body perforation dating back at least 12,000 years, yet this new discovery represents the earliest confirmed piercings found on actual bodies.

“We knew that there were earring-like artifacts in the Neolithic, they have been found at many sites,” explained study author Dr Emma Baysal in a statement via email. “But we were lacking in situ finds confirming their use on the human body before the late Neolithic.”

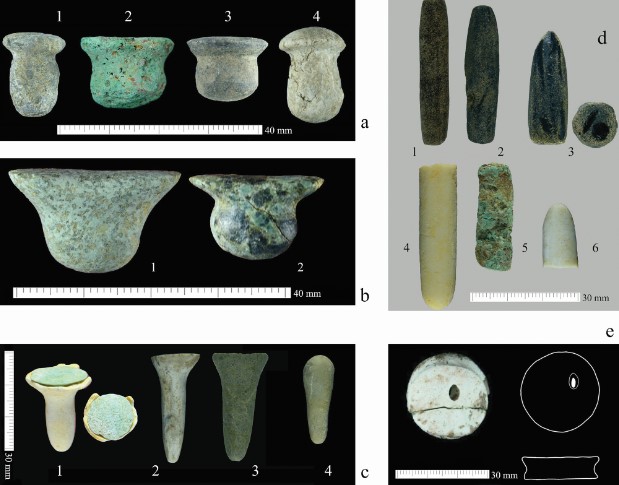

Researchers discovered seven different piercing types.

The objects were found at the Stone Age site of Boncuklu Tarla, which dates back to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. Unlike other similar prehistoric artifacts, these ornaments were found around the ears and mouths of the skeletons buried at the site, indicating that they were definitely used as piercings.

In total, the study authors discovered 106 items that were clearly intended for this purpose, of which 85 were complete enough to be analyzed. These were mostly made of limestone, river pebbles, or obsidian and had a minimum diameter of 7 millimeters (0.28 inches), thus requiring a large perforation in the wearers’ skin.

The prehistoric piercings were worn in the ears and lip.

Seven different piercing types were identified, some of which were found in or around skeletons’ ear canals and therefore categorized as ear piercings. Others were discovered within the neck or ribcage area, close to the chin, indicating that they were worn as a type of lip stud called a labret.

Further proof for the use of lip labrets came from an artifact found within the oral cavity of a skeleton. Osteological analysis then revealed a particular pattern of wear on this individual’s lower incisors that is not linked to diet and was likely to have been caused by repeated contact with a stone piercing beneath the lower lip.

The piercings were discovered on or close to the skeletons’ ear canals or mandibles.

Importantly, the study authors note that these ornaments were only found in adult graves and appear not to have been associated with children. This leads them to suspect that body piercing was a rite of passage, conducted to initiate older adolescents into adulthood.

Such a ritual may have been intended to produce a noticeable alteration in an individual’s persona as they reached maturity. For instance, the authors explain that “labrets also cause significant change to the way in which the wearer speaks, eats and breathes, so that this physical augmentation produces a multisensory change perceived by both wearer and viewer.”

More generally, Baysal says that the Neolithic inhabitants of Boncuklu Tarla clearly “had very complex ornamentation practices involving beads, bracelets and pendants, including a very highly developed symbolic world which was all expressed through the medium of the human body.”

Moreover, she says her team’s findings show “that traditions that are still very much part of our lives today were already developed at the important transitional time when people first started to settle in permanent villages in western Asia more than 10,000 years ago.”

The study is published in the journal Antiquity.

Source Link: 11,000-Year-Old Earrings And Lip Studs Are World’s Oldest Piercings