London in the early 1780s was a tumultuous place. At the start of the decade, anti-Catholic riots, known as the Gordon Riots, had caused chaos in the city, leaving hundreds dead and many parts of the city in cinders. Across the Atlantic, the American Revolution was in full swing, so political attention was trained on the New World. Then, only 18 months after the Gordon Riots, a new threat appeared that stirred further unease for the recovering city: the caterpillars had arrived.

Throughout the city and the surrounding countryside, foliage disappeared under sheets of tangled nests made by brown-tail moth caterpillars. It’s all natural enough, but at the time, these little critters had the potential to spark widespread panic as they could be seen as portents or indeed harbingers of plague or famine.

As with so many lesser-known moments in history, this one weird but deeply fascinating event provides incredible insights into various aspects of life in late 18th-century Britain. Not only did the appearance of the caterpillars baffle people, highlighting disparities in literacy and education levels in the wider population, but the whole incident ignited a form of expertise war we often see on social media today. On the one hand, you have someone with dubious credentials attempting to capitalize on the issue, and on the other, you have a more recognized “scientific” authority attempting to downplay and fact-check the situation. Welcome to the London Caterpillar Outbreak of 1782.

The story of this odd moment in the spring of 1782 was recently published in an article by Johan Lidwell-Durnin, a historian at the University of Exeter. Lidwell-Durnin’s assessment provides a brilliant account of how different people responded to the arrival of this swarm of creeping little nest builders, demonstrating how various contemporary forces overlap to turn something “normal” into something significant.

But before diving into the events themselves, it is worth saying something about one of the antagonists in this tale.

Brown-tail moth caterpillars are not and were not unknown creatures. Adult moths are white with very obvious brown hairs on their lower abdomen – hence the name. They are generally active between July and August in Britain, and lay batches of 150 to 250 eggs on trees and plants like hawthorn, blackthorn, plum, cherry, rose, and blackberry. When their caterpillars hatch, they start to snack on the host plant but also start to spin webbing, which will eventually become caterpillar-sized sleeping bags to keep them warm over the winter. Then, in the following spring, the caterpillars wake up and start feeding again, creating extensive webbing and stripping plants bare.

Generally speaking, they’re a pest for anyone growing these plants, but they are otherwise mostly harmless – they do shed hairs that can cause pretty nasty irritation and rashes to skin, so best to avoid them. They certainly are not capable of spreading plague or causing mass fatalities. But not everyone in 18th-century London knew this. Unless you were a natural philosopher (basically a proto scientist), a medical student, or a farmer, you probably had little chance to learn about these caterpillars. So, when the infestation of them appeared in 1782, the public mostly heard about them through newspapers that described them as carriers of disease.

History is a fickle thing and loves to throw in events to muddy the water, something that conspiracy theorists love. In this instance, the caterpillars’ appearance just happened to coincide with an outbreak of influenza, which contemporary physicians believed had started in the poorer suburbs. These just happened to be the places where the caterpillars were most numerous. It didn’t help that, after the newspapers suggested destroying the nests with fire, multiple people reported nausea and skin issues from coming into contact with the caterpillar’s hairs.

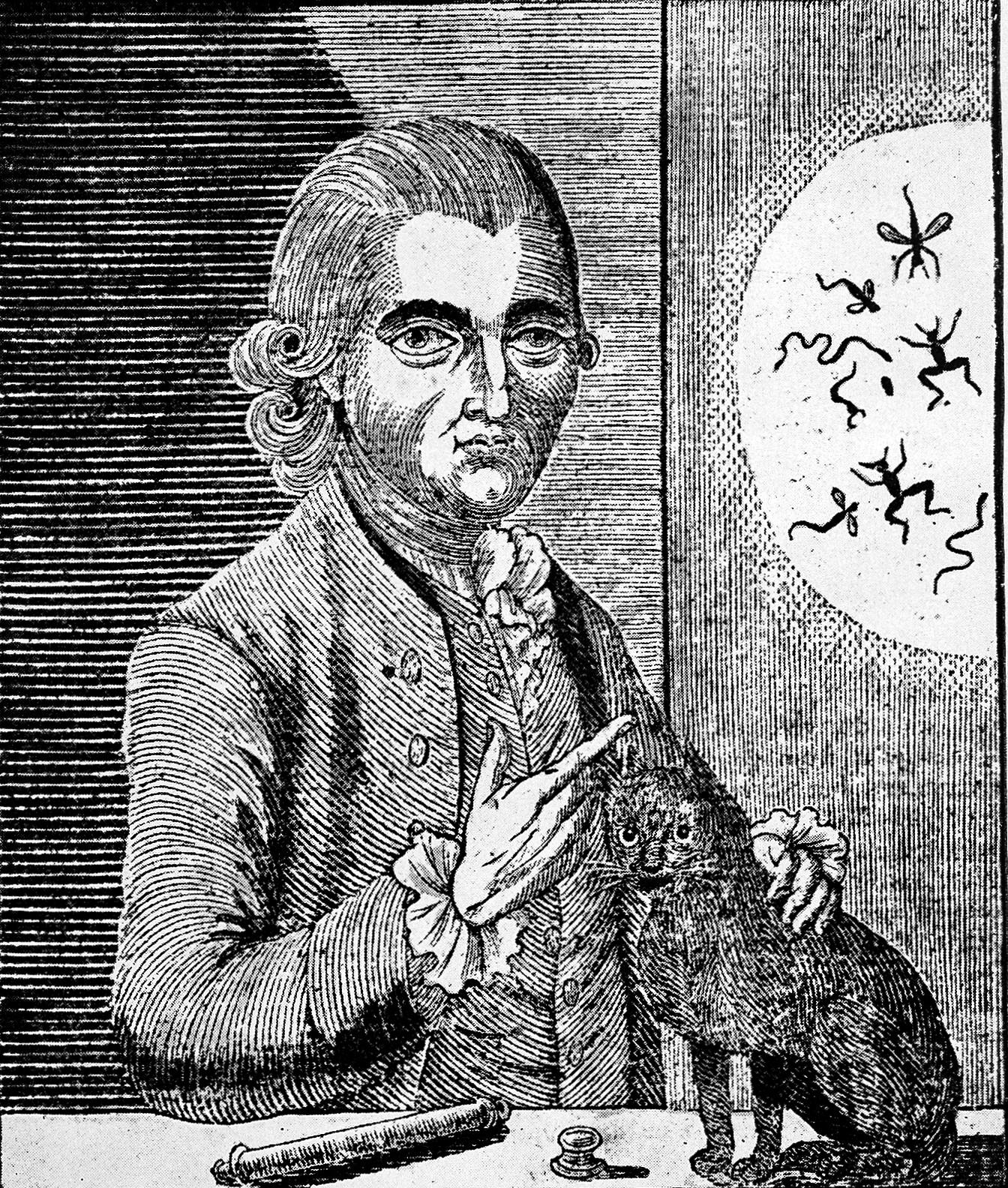

And of course, when there’s trouble, there’s also someone willing to profit from it. In this case, a man named Gustavus Katterfelto played a big role in stirring up public concern. Katterfelto published sensational notices that accused the caterpillars of bringing plague and famine upon the city. Katterfelto also put on shows where he projected enlarged images of the insects on the walls for people to see, while also offering cures and tonics that could protect them from the illness he foretold.

Gustavus Katterfelto had identified small creatures living in water and used to show projections of them to wondering audiences. He also started arguing for a form of germ theory as he believed these little creatures caused disease.

Katterfelto is quite an ambiguous character. He was a showman who could entertain a crowd with magic tricks (and a black cat he claimed to be the Devil) one minute and then produce examples of the latest scientific apparatus and wow an audience with his knowledge in another. He had objects like solar microscopes and air pumps that he would display to the public, and he also lectured on topics that ranged from mathematics and magnetism to electricity.

Katterfelto is an example of how science at this stage was not a coherent discipline practiced by a specific group of specially trained people in laboratories, but was tied up with showmanship and public spectacle too. Here, some of the famous luminaries of 18th-century science competed and performed alongside others who we would consider quacks and pseudoscientists today.

It was a messy situation, and the caterpillar outbreak demonstrates how scientific authority was starting to assert itself, Lidwell-Durnin makes clear. To dampen the fires of fear, entomologists, like William Curtis and Joseph Banks, as well as other natural philosophers, published pamphlets that attempted to explain the true nature of the wriggling invaders.

In the end, there was no plague and no famine. As Katterfelto’s predictions failed to manifest, he became more of a figure of public ridicule and satire. But Lidwell-Durnin makes clear that even for individuals like Banks who attempted to combat the more sensationalist views, some still believed the weird appearance of the caterpillars had to mean something. After all, this was a period when natural phenomena were still interpreted as being signifiers of broader forces at play in the world.

“The insects were a potent threat; they had arrived without warning, and much of the public debate was over what they foretold concerning the near future. Entomology and scientific authority provided only one means of reading the signs writ over the trees of the metropolis,” Lidwell-Durnin writes in his study.

As such, at this time in history, the interpretation offered by natural philosophers, the vanguard of the Enlightenment, was still discordant, as the caterpillars demonstrated.

Source Link: 1782, The Year A Caterpillar Outbreak Terrified London