Fire, as you learn from a very young age, is as dangerous as it is hot. If you see it and you don’t have the equipment to put it out, it is best to keep your distance – but not all fires are visible under normal conditions.

Hydrogen, for example, burns with a very pale blue flame that is almost invisible in daylight. This, combined with hydrogen’s tendency to leak through the tiniest of gaps, is a problem for organizations that work with it, such as NASA.

In 2003, NASA and the Florida Solar Energy Center came up with a solution in the form of a tape that changes color when exposed to the element. Before that, ultraviolet sensors were used to detect flames. The solution used before that, however, was far less dignified – and a whole lot more fun.

“Given those stakes, imagine the task of having to monitor liquid hydrogen as it flows through a few miles of pipeline—which is what NASA had to do in preparation for every Shuttle launch, when hundreds of thousands of gallons were transferred from a holding tank to the launch pad for fueling,” NASA explained in a blog post.

“In the Apollo days, detecting a flame from one of those leaks was accomplished by using the ‘broom’ method, whereby workers would take a broom and walk around with the head stretched out in front of them. If the head began to burn, there was a leak.”

It was effective, even if it probably wasn’t too reassuring to astronauts that the organization sending them to space found leaks by waving around brooms.

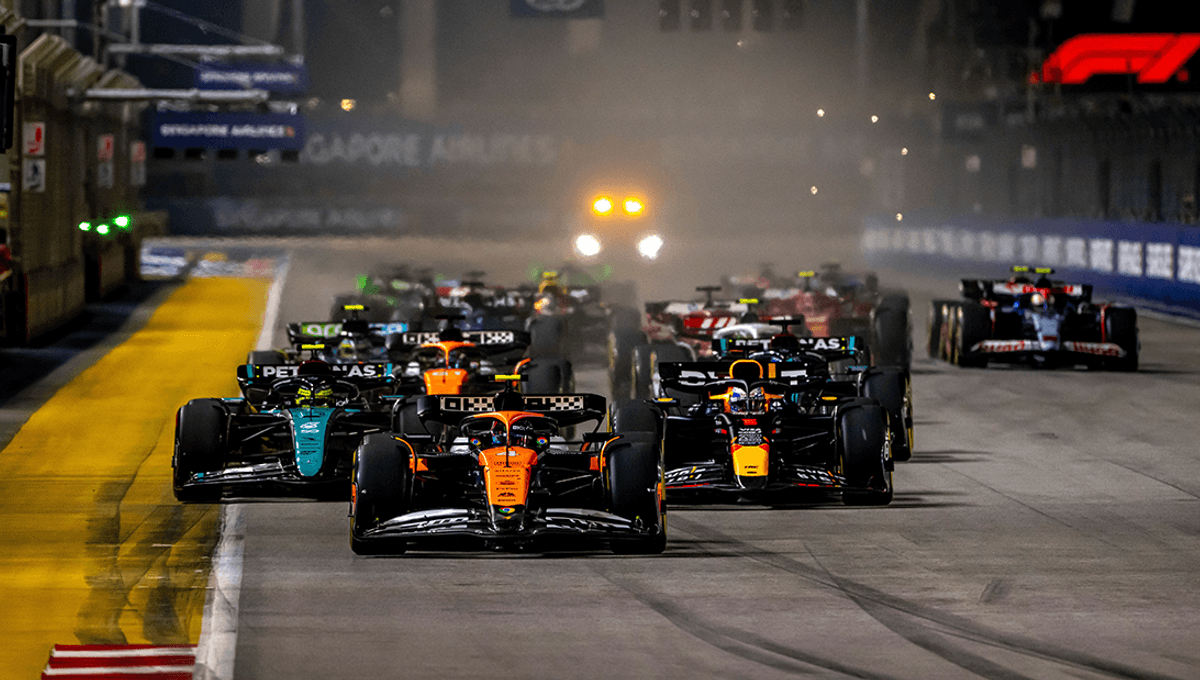

Methanol fire is similarly invisible and dangerous in daylight, as demonstrated in 1981 when racing driver Rick Mears was briefly set alight during a pit stop during the Indianapolis 500 race.

During a pit stop, methanol – used as fuel in the vehicles – was inadvertently sprayed over Mears’ car as well as the surrounding area and pit crew. Some of the methanol, which caught alight, entered the cockpit and covered his helmet and suit. When he attempted to breathe, as well as escape, the flames entered his helmet, burning his nose.

“I quit breathing fortunately, but I didn’t have a breath because I was struggling to get out, and I kind of kept trying to keep my eyes closed so that it wouldn’t burn my eyes,” Mears later said of the incident. “I got unbuckled, got the wheel loose, I don’t remember now what all the scenario was, but you know ended up working my way out”.

Several other crew members caught alight, as they could not see the flame and approached.

In regular, visible fires, the color comes from a hot soot of carbon monoxide, elemental carbon, and carbon radicals. It is the soot reacting with oxygen molecules that is responsible for the yellow/orange hues you see in fire, while unburned soot is the smoke you see rising above it.

Being invisible, it poses more challenges to firefighters, requiring special treatment.

“Dry chemical powder, carbon dioxide and alcohol-resistant foam extinguish methanol fires by oxygen deprivation. Firefighters should use full-face, self-contained breathing apparatus, and wear impervious clothing, gloves and boots,” the Methanol Institute explains. “For larger fires involving a tank, rail car or tank truck, isolate for ½ mile in all directions, also consider evacuation for ½ mile in all directions.”

Source Link: 1981 Racing Car Incident Shows Why Invisible Methanol Fires Are So Dangerous