A hoard of ancient plant DNA has been extracted from a nearly 3,000-year-old clay brick, revealing a time capsule of ancient flora in what is now northern Iraq. The authors adapted a technique that’s normally used in materials like bone, and now say that it could be applied to clay artifacts recovered from sites around the world.

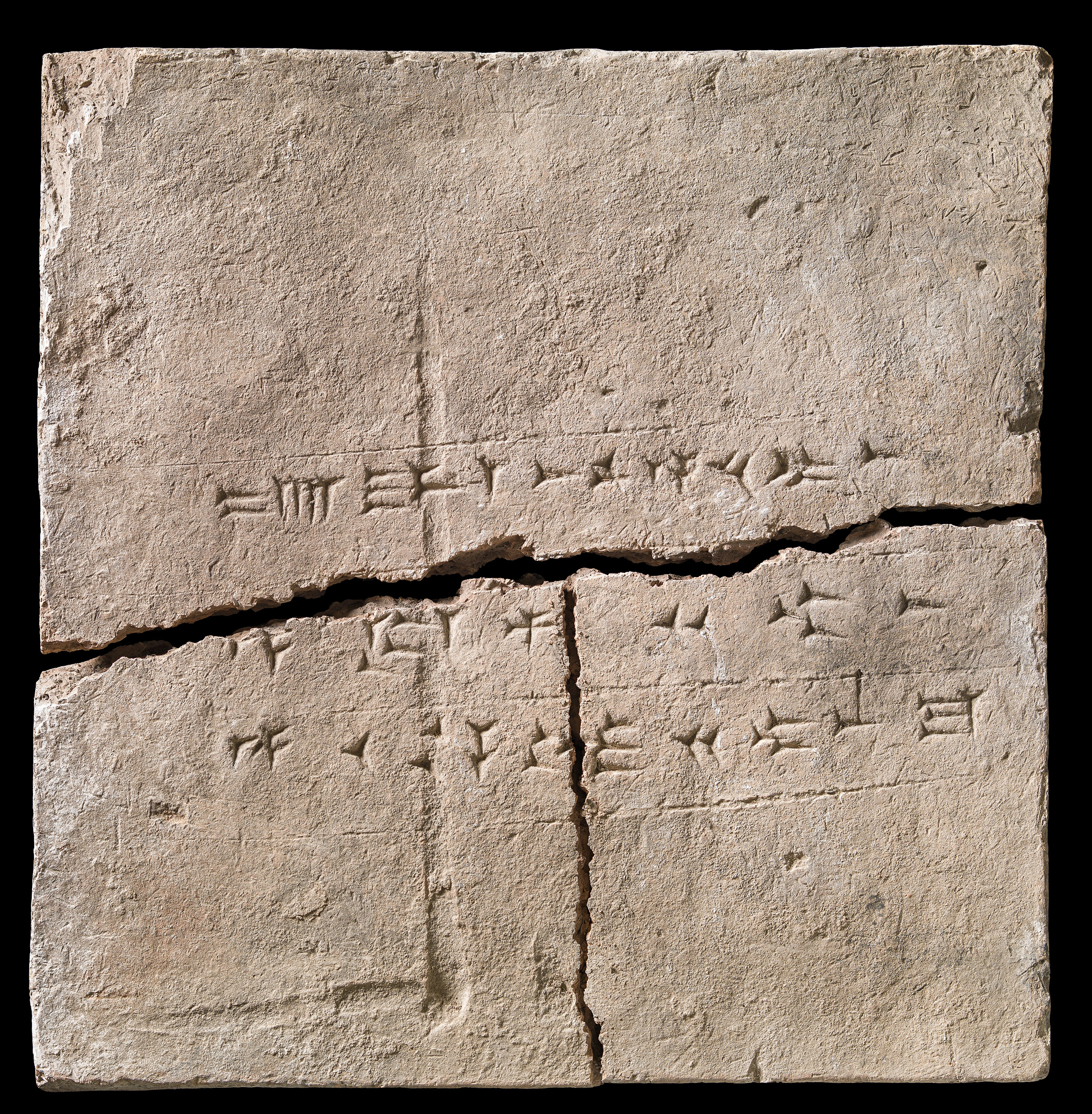

The clay brick dates back 2,900 years, when it was used in the construction of the palace of Neo-Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II in the ancient city of Kalhu, known latterly as Nimrud. This precise dating of the artifact was made possible thanks to the inscription it bears – written in Akkadian using cuneiform script, it clearly states, “The property of the palace of Ashurnasirpal, king of Assyria.”

The brick now resides at the National Museum of Denmark, and it was during a digitization project at the museum in 2020 that researchers realized it might be possible to extract DNA from its inner core, which could have lain there, protected from contamination, for millennia.

The craftspeople of the time made this type of brick by sun-drying a mixture of mud, straw, and sometimes animal dung. The fact that the clay was not exposed to the extreme heat of a fire means any genetic material trapped within it would have a good chance of surviving down the ages.

The complete brick, in its current home at the National Museum of Denmark.

Image credit: Arnold Mikkelsen og Jens Lauridsen

By adapting a protocol that’s normally used to obtain DNA from bones, the team successfully collected and sequenced DNA that dates back to the brick’s creation, between 879 and 869 BCE.

“We were absolutely thrilled to discover that ancient DNA, effectively protected from contamination inside a mass of clay, can successfully be extracted from a 2,900-year-old clay brick,” said joint first author Dr Sophie Lund Rasmussen, of the University of Oxford, in a statement.

By comparing the sequences of the extracted DNA with modern botanical records from the region, as well as ancient Assyrian plant descriptions, the team was able to identify 34 different taxonomic groups of plants, including cabbages (Brassicaceae), heathers (Ericaceae), laurels (Lauraceae), and grasses (Triticeae).

“Because of the inscription on the brick, we can allocate the clay to a relatively specific period of time in a particular region, which means the brick serves as a biodiversity time-capsule of information regarding a single site and its surroundings. In this case, it provides researchers with a unique access to the ancient Assyrians,” explained joint first author Dr Troels Arbøll, also of the University of Oxford.

Not only has this project shed new light on the plant species that were present here thousands of years ago, but it also opens up the possibility of using the technique to reveal the secrets hidden in other artifacts. Clay objects are ubiquitous at archaeological sites around the world and can often be precisely dated, so there’s a wealth of other materials that could now be explored.

And it’s not only plant DNA. In this particular case, the plant genetic material was the most abundant and best preserved, but there’s no reason why other relics might not yield animal or insect DNA. Knowing more about ancient biodiversity helps provide valuable context for researchers looking at present-day species loss.

Add that to the potential for new insights into lost civilizations, and it’s clear how this could be a boon for scientists across many disciplines.

“This research project is a perfect example of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in science, as the diverse expertise included in this study provided a holistic approach to the investigation of this material and the results it yielded,” said Dr Rasmussen.

The study is published in Scientific Reports.

Source Link: 2,900-Year-Old Brick From Royal Palace Wall Reveals Treasure Trove Of Ancient Plant DNA