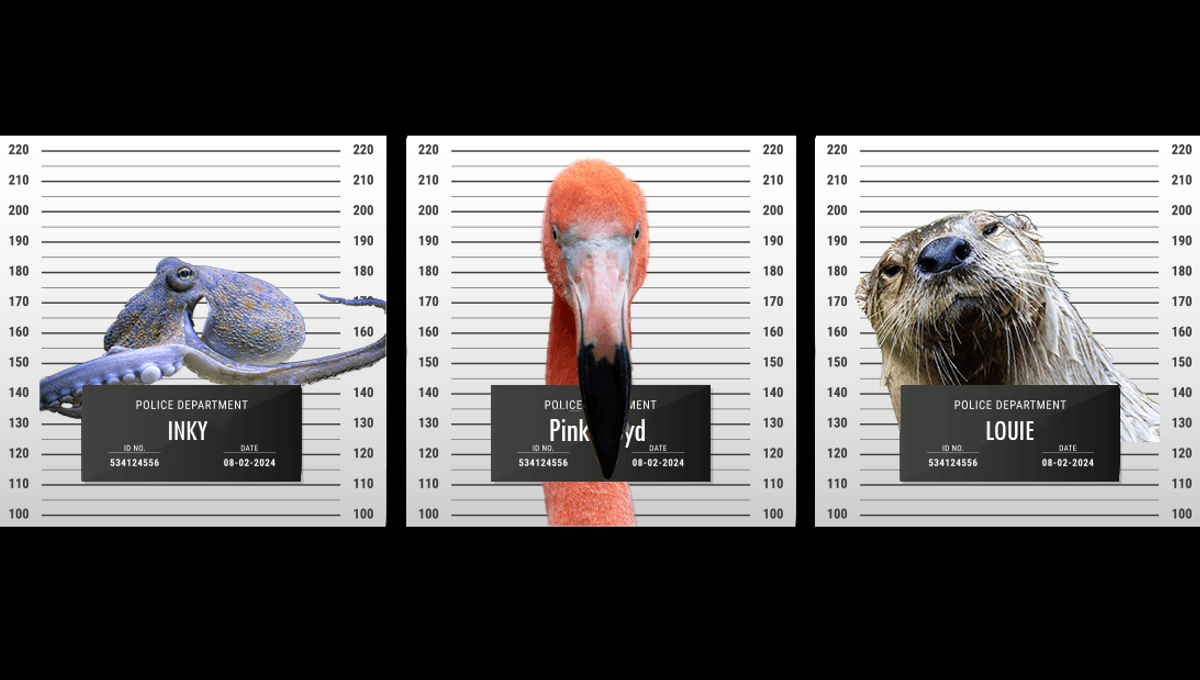

Here are some of the best.

Louie the otter

Careful planning and strategizing is great, but sometimes, you’ve just got to cut it and run. That’s what Louie the otter did earlier this year, and he’s never been happier.

“Due to the length of time that Louie has been missing, we believe he has made the decision to be a wild otter,” announced New Zoo Adventure Park in Wisconsin, where the otter had previously been living, on May 30. “We accept this, although we would, of course, welcome him home if he decides to return.”

By that point, Louie had been on the lam for more than two months – and his escape was far from subtle. “Tracks in the fresh snow were evident,” the zoo wrote after the March 20 breakout of Louie and his best gal Ophelia, “and overnight camera footage showed that both otters appeared to have enjoyed the snowfall, romping around the zoo, frequently sliding on their bellies and exploring nearby water bodies.”

After that, they disappeared – more or less. A few people saw them gallivanting around in the nearby area, but traps failed to apprehend them. It was, the zoo pointed out, otter mating season, so the fact the pair had gone off the grid wasn’t totally concerning – and besides, both were wild-born locals, so they knew how to survive and thrive in the area. “The Zoo is surrounded by natural ponds and other waterways,” the zoo assured readers, “which provide ample food and safe places to sleep even at this time of year.”

But evidently, not all of us are built for life on the run. On April 1 – the zoo was careful to confirm that “this is NOT an April Fool’s Day trick” – Ophelia came back to the zoo. She was found to be perfectly healthy, albeit alone, and taken back to her life of luxury in the otter enclosure.

Louie, however, never returned. “Louie was born in the wild and grew up long enough in the wild to learn and practice all the skills a river otter requires to survive,” the zoo explained. “We expect that he’s doing just fine out there.”

“We are working with the North American River Otter Species Survival Plan managers to identify another male otter that would be a good match for Ophelia,” they added. Get it, girl.

Pink Floyd the flamingo(es)

There are some names that come with certain… reputations. You wouldn’t name a baby Lucifer, for example; neither would you call a dog Baby Killer 3000, the Baby Killing Dog. It’s just tempting fate.

Well, here’s another one: don’t call a flamingo Pink Floyd. In 1988, one such named bird escaped from Tracey Aviary in Utah – and then, in 2005, another one fled the Sedgwick County Zoo in Wichita, Kansas. Clearly, this name is one that destines its owners to go…… On The Run.

You might think, being birds, escapee flamingoes would be almost unavoidable. The fact that they’re not is a result of a controversial procedure known as pinioning, in which a couple of bones in the wing are amputated, permanently removing their ability to fly.

But here’s the thing: pinioning is rarely performed in adult birds. Whether it’s ethical or not in babies may still be debated, but for adults, it’s objectively dangerous and traumatic. Both Pink Floyds were adopted into their respective zoos as adults – and so, in both cases, it was decided that the procedure was simply not a viable option for grounding the birds.

Instead, they went for a much less dramatic option: wing clipping. That’s exactly what it sounds like: the flight feathers are clipped off, “no different than you or I getting a haircut,” Scott Newland, curator of birds at Sedgwick County Zoo, told The New York Times in 2018.

The trouble with haircuts, though, is that they’re temporary. Hair grows back – and so do feathers. Wing clipping, therefore, has to be repeated every year after molting season. The zookeepers of Tracey Aviary and Sedgwick County simply… didn’t get there in time.

“[Pink Floyd] apparently figured out he could fly before we got his wings clipped,” Mark Stackhouse, the then aviary education coordinator, told the Utahn Deseret News in 1989. And in 2005, the Kansan Pink Floyd’s scheduled clip was delayed by bad weather – setting up his majestic escape for, no joke, Independence Day.

Both birds were wildly successful in their flights to freedom. The first made it as far as the border between Idaho and Montana, where he spent his summers – his winters were spent on the Great Salt Lake in Utah – and the second made it all the way from Kansas to the Gulf of Mexico.

“The 600-mile journey it took to get to [Texas’s Gulf coast] is kind of surprising,” Joe Barkowski, then the zoo’s curator of birds, said at the time. “We’re not seeing migrations of that distance a lot.”

Keepers did try to retrieve both Pinks Floyd – but frankly, if a flamingo doesn’t want to be got, you ain’t getting it.

“Flamingos are very smart and very capable, and he just didn’t want to be retrieved,” Jennica King, a spokesperson for Sedgwick County Zoo, told The Washington Post in 2022, when Kansas Floyd was last spotted. “And […] Good for him. He’s living his best life down in Texas.”

Inky the octopus

Remember how in Finding Nemo, the captive fish all concocted that intricate and laughably long-shot escape plan involving one of them squeezing through a tiny sanitation tube, leaving the tank itself, and finally making it out to the South Pacific Ocean? Well, Inky did that for real.

“He managed to make his way to one of the drain holes which go back to the ocean and off he went,” Rob Yarrall, manager of New Zealand’s National Aquarium, told Radio New Zealand in 2016. “[A]nd he didn’t even leave us a message.”

Like the other animals we’ve seen, Inky was born in the wild – but in 2014, after he was found scarred and injured in a crayfish pot, he was taken in by the aquarium. “He’s got a few battle scars and a couple of shortened limbs which will eventually grow back,” said Kerry Hewitt, the curator of exhibits at the Aquarium, at the time, “but he’s getting used to being at the aquarium now.”

“We have to keep Inky amused or he will get bored,” she added.

But whether due to their diversions falling short or a simple call to freedom, Inky’s stay was destined to be temporary. That is, thanks to octopodes’ high intelligence and extreme squishability, not all that surprising: “They are very strong,” Jennifer Mather, a comparative psychologist at Canada’s University of Lethbridge, told Scientific American in 2009.

“It is practically impossible to keep an octopus in a tank unless you are very lucky,” she said. “[They] simply take things apart.”

Source Link: 3½ Tales Of Daring Animal Escapes