Some 3,000 meters (9,843 feet) beneath the Arctic Ocean, scientists are exploring a bubbling field of hydrothermal vents along the Knipovich Ridge near Svalbard, the northernmost settlement on Earth.

The hydrothermal vent field was recently discovered on the seafloor within the triangle between Greenland, Norway, and Svalbard on the boundary of the North American and European tectonic plates.

Using a remotely controlled sub, researchers at the University of Bremen’s Center for Marine Environmental Sciences (MARUM) gathered samples and data from the hydrothermal vent field, which they named Jøtul after a giant in Nordic mythology.

Hydrothermal vents are found at junctions of shifting tectonic plates where geothermal activity is at its most intense. They form when water penetrates the ocean floor and becomes heated by magma from the bowels of the planet. The superheated water then rises back to the sea floor through cracks and fissures, becoming enriched with minerals and materials dissolved from the oceanic crustal rocks.

Despite being a major junction of tectonic plates, no hydrothermal vents were previously known to be located on the Knipovich Ridge – until now.

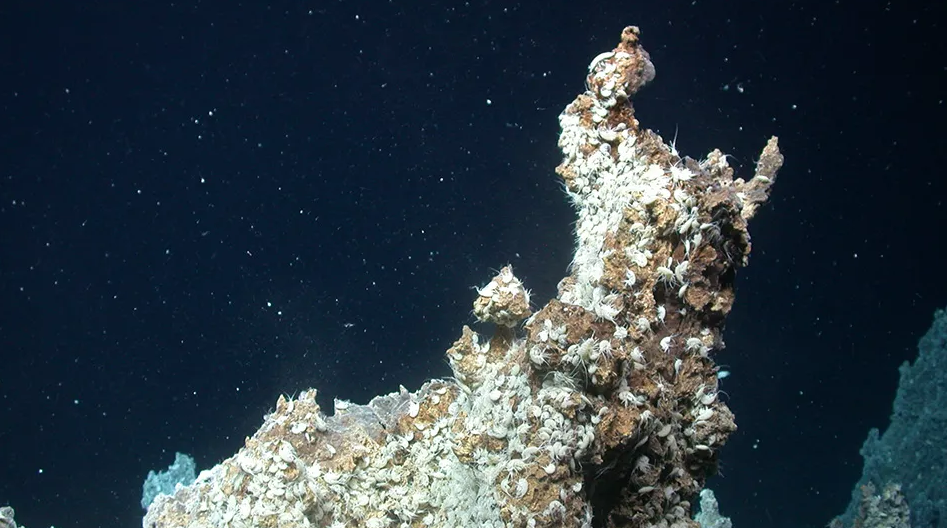

Some of the hydrothermal mounds were home to organisms, including tiny crustaceans.

Image credit: MARUM/University of Bremen

The Knipovich Ridge is particularly special because it wasn’t formed by two plates crashing together, but by two plates moving apart at a rate of less than 2 centimeters (less than 1 inch) per year, known as a spreading ridge.

Very little is known about hydrothermal activity on slow-spreading ridges, so the team is keen to learn about the chemical composition of the escaping fluids, plus the geological features formed by its heat and minerals.

Some of the fluids gushing out of the Jøtul Field are unbelievably hot, measuring up to 316 °C (601°F). When the superheated fluid makes contact with the frigid waters, the minerals solidify, forming large chimney-like structures called black smokers.

Another interesting feature of the Jøtul Field is that its hydrothermal fluids are rich in methane, a potent greenhouse gas, as well as carbon dioxide, the primary greenhouse gas. This means that the region might have some implications for climate change and the carbon cycle in the ocean.

Strange and wonderful lifeforms can often inhabit fields of hydrothermal vents. In the pitch-black depths of the ocean where photosynthesis is impossible, hydrothermal fluids provide the foundation for chemosynthetic organisms, which obtain nutrients through chemical energy rather than sunlight.

An in-depth understanding of the field’s biodiversity is not yet available, although it will no doubt be a point of interest for the researchers at MARUM, who plan to return to the area in late summer 2024.

The study is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Source Link: 300°C Liquid Oozes From Chimney-Like Vents Deep Below Arctic Ocean