Tracks found in early Carboniferous-period rocks in southeast Australia appear to be from an amniote, most likely a reptile. If so, these beat the previous oldest evidence for amniotes by more than 30 million years, and will rewrite the timing on when the clade that includes mammals first evolved.

The first vertebrates to leave the oceans remained dependent on water to lay their eggs, like modern amphibians. Professor John Long of Flinders University told IFLScience that consequently, “They couldn’t live far from water.” This left much of the planet to invertebrates such as insects and giant millepedes.

Vertebrates’ big advance came with the development of hard-shell eggs, which rely on an protective membrane known as an amnion. Reptiles and birds are obvious descendants of the first amniote, but as mammals we are a branch-off that still falls under the clade as we still produce an amnion while our embryos develop. While this history is agreed on, the timing is much more uncertain, and Long is part of team that have changed the game.

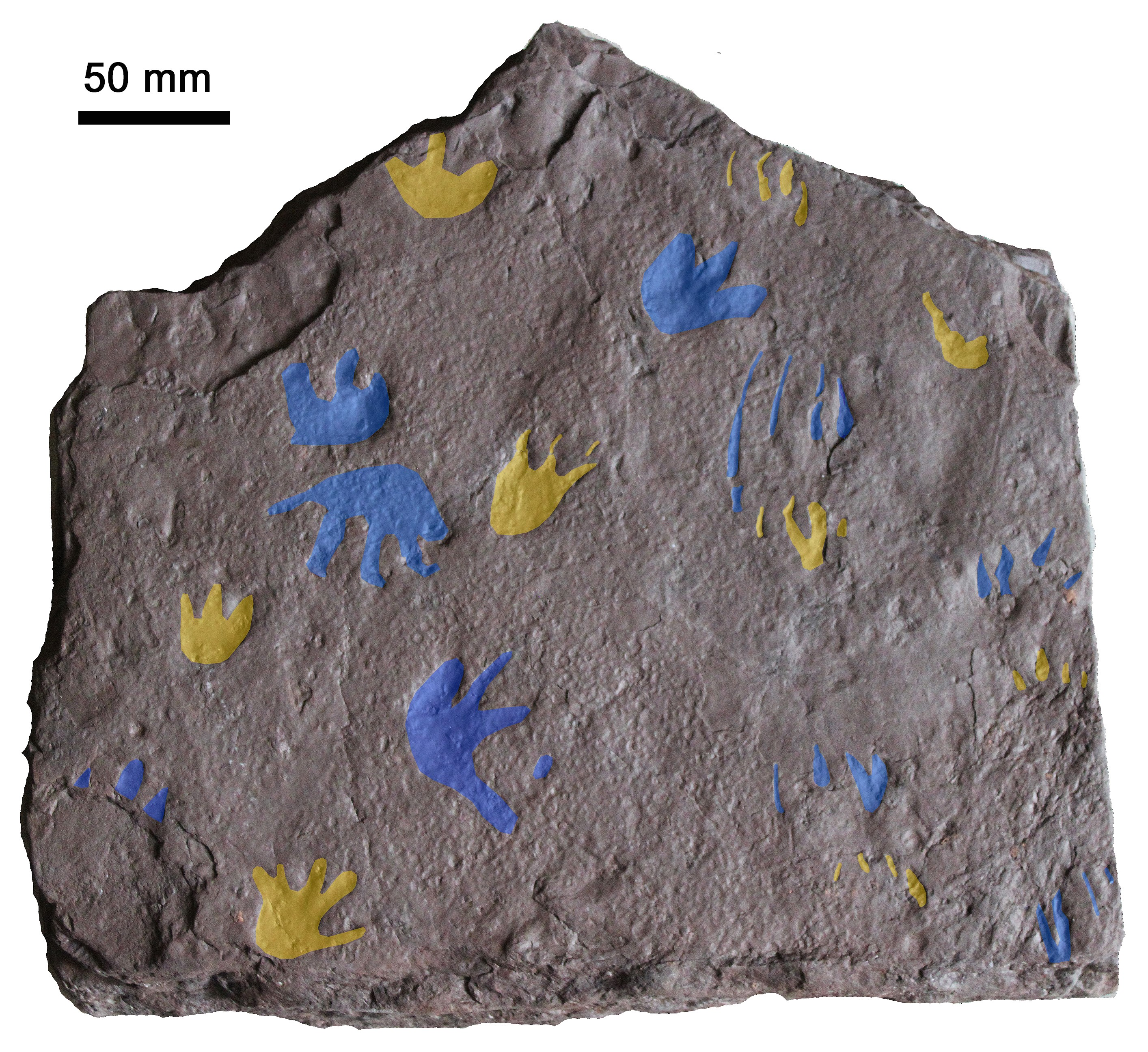

After being alerted by locals to something remarkable near Mansfield, Victoria, Long and colleagues found a series of footprints in stone that was mud around 355 million years ago. “It was amazing how crystal clear the trackways are on the rock slab. It immediately excited us, and we sensed we were onto something big – even though we had no idea just how big it is,” Long said in an emailed statement. The clarity is so good, palaeontologists can even spot marks left by raindrops between when two animals walked across the mud. Closer examination revealed what Long calls “very precise scratch marks,” which could only be made by a claw.

The tracks colored to make their shapes clear, including the claw marks.

Image credit: Grzegorz Niedzwiedzki

Useful as claws are for fighting, digging, or climbing trees, no modern amphibians have them, perhaps because they seldom do the latter two. “We have a huge number of fossil amphibian skeletons and none have claws,” Long told IFLScience. The maker of the tracks can’t have been an amphibian.

Tetrapods (all vertebrates other than fish) are thought to have evolved during the Devonian (often called the age of fishes), based on the extent they had diverged by the late Carboniferous. However, it was thought the amniotes were a Carboniferous development, possibly a consequence of the late Devonian mass extinctions and the ecological niches that opened up.

Long claims the trackway can “falsify this widely accepted timeline.” Although the tracks were made in the Carboniferous, something this advanced does not evolve overnight. Long sees this as evidence amniotes were present in the Devonian. Whether the mass extinctions, which were so drastic in the oceans, also affected land animals, is unknown, but a few million years later it looks like the amniotes were taking over the planet.

The discovery has shaken scientists far beyond Australia. “I’m stunned,” said Professor Per Ahlberg of Uppsala University in another statement; “A single track-bearing slab, which one person can lift, calls into question everything we thought we knew about when modern tetrapods evolved.”

Without a skeleton, it’s not possible to confirm the track-maker was a reptile, but the authors are calling it “reptile-like”. Long suspects it would have resembled the goannas that populate the area today.

Professor John Long comparing the tracks to a modern iguana foot, a model for the animal that made them.

Image credit: Traci Klarenbeek

Long noted the most important implication of the discovery is that “it pushes their evolution back by 35-to-40 million years older than the previous records in the Northern Hemisphere.” It also suggests amniotes’ origins may have been in Gondwanaland, of which Australia was then part.

Long told IFLScience the age of the tracks could be narrowed down to a 9-million-year interval. The rock the marks are found in is part of an extensive layer deposited around the same time. It lies above Devonian bedrock 359 million-years-old, and in other parts of southeastern Australia is covered by volcanic deposits that can be dated with certainty to 350 million years old.

The track size and spacing indicate an animal perhaps 80 centimeters (32 inches) long, although such estimates are vague without knowing more about the body plan, Long said.

While the team were studying the Australian trackway, another amniote track was found in Poland. Not as old as the Australian one, the Polish discovery nevertheless would have set the record without this find. It both provides confirmation for amniotes earlier emergence and proves their range extended beyond Gondwanaland – unsurprisingly given how little competition they would have faced away from freshwater.

Tracks are sometimes regarded as the poor relations of palaeontology, what you use when you don’t have bones or teeth to reveal a species’ build. However, co-author Dr Aaron Camens looks at it differently, saying, “A skeleton can tell us only so much about what an animal could do, but a trackway actually records its behaviour and tells us how this animal was moving,”

The study is published in Nature.

Source Link: 356-Million-Year-Old Fossil Trackway With Claw Marks Is Probably Oldest Evidence Of Reptiles