Fragments of ancient household item unidentified for 90 years after being excavated have been found to be pieces of baby rattles from 4,000-4,500 years ago. The discovery offers archaeologists a chance to learn how these implements have changed, and how they have not, in all that time

Dr Mette Hald of the National Museum of Denmark is seeking to shift the focus of archaeology away from the rich and powerful by looking at items from ordinary neighborhoods of Hama, Western Syria from 2000-2500 BCE. Haid and colleagues have now published a paper on a particularly neglected household item: baby rattles. In fact, it studies the largest sample of these rattles yet collected from the Near East. Despite being broken over four millennia ago, the number of rattle fragments offers a chance to learn how people in the Early Bronze Age kept their infants amused.

Twenty-one clay fragments collected in Hama, Western Syria in the 1930s are held in the National Museum of Denmark, having been designated merely as handles of unknown items when first discovered. They haven’t attracted much attention since.

However, colleague and first author Dr Georges Mouamar noticed their similarity to two complete clay gourd rattles from the Al-Zalaqiyat Cemetery north of the city from around the same time. Now that their likely purpose was known, Haid, Mouamar and colleagues set about looking for patterns among this much larger sample. Fortunately, despite the low importance ascribed to them, detailed records were kept of the context in which each item was found.

Nineteen of the fragments are indeed handles, while the other two appear to be parts of the rattle itself. Most are hollow and some painted. Some also have flat bases, apparently so they could be stood upright. The mix of strata in which the items are found suggest style variations persisted over the centuries, rather than some displacing others.

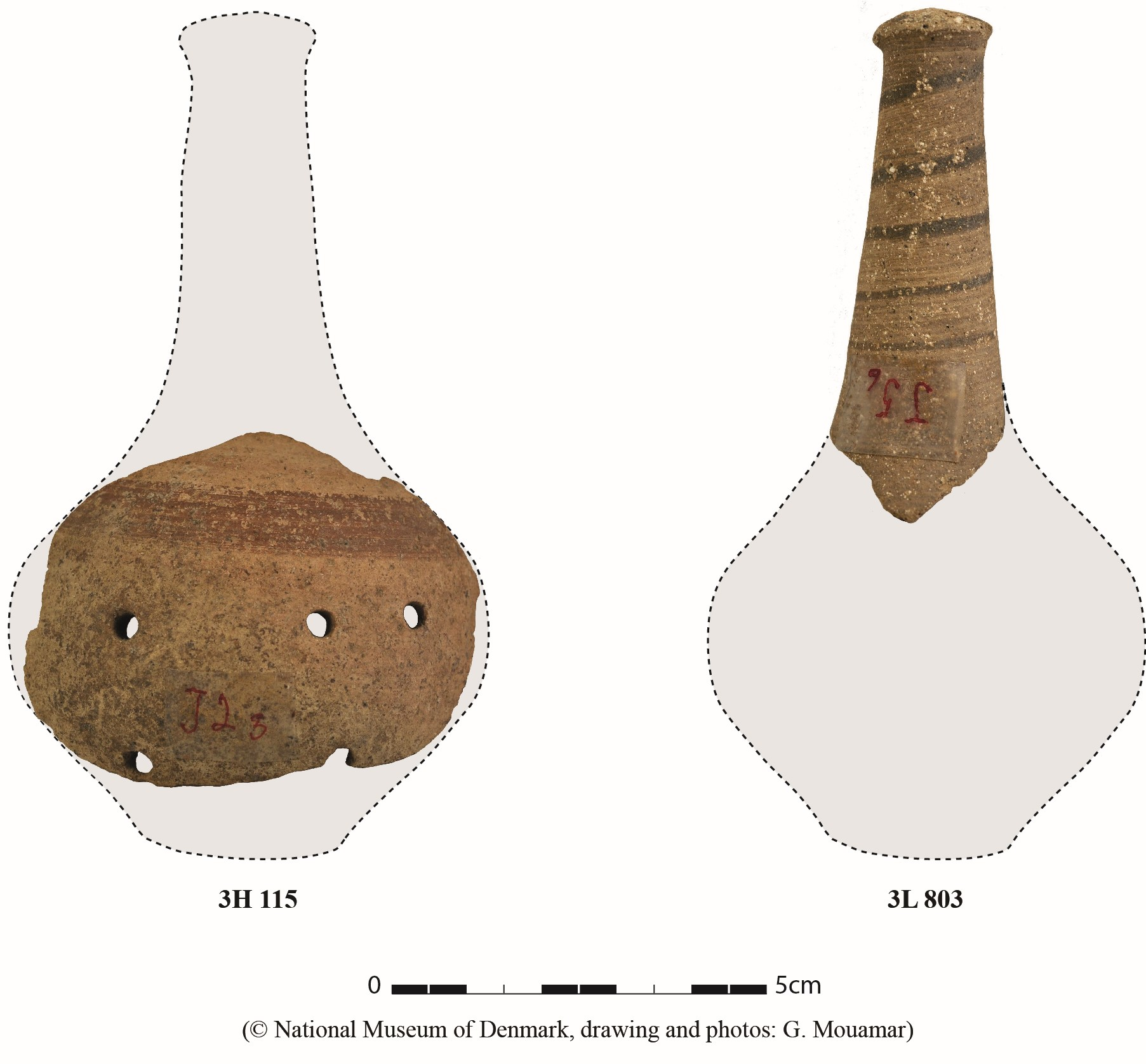

Reconstruction of the shape of the original rattles based on the surviving pieces.

Image credit: National Museum of Denmark, drawing and photos: G Mouamar

“All the rattles from Hama come from what seems to be an ordinary domestic neighbourhood,” the authors observe.

“It shows us that parents in the past loved their children and invested in their wellbeing and their sensorimotor development, just as we do today,” Hald said in a statement. “Perhaps parents also needed to distract their children now and then so that they could have a bit of peace and quiet to themselves. Today, we use screens, back then it was rattles.”

The complete rattles had tiny holes in them, and one still had small stones inside when excavated. Other rattles have been found from tombs from the era, but never in numbers like these, which demonstrate what common household implements they must have been.

“The material inside is of stone or baked clay, none of which degrades, and the holes in the body of the rattle are too small for the stone/clay to fall out,” Hald told Phys.org.

The authors conclude the rattles were not loud enough when shaken to have been used as musical instruments, but would have worked well for amusing babies, as remains popular today, despite greatly expanded toy options.

Consequently, it’s not surprising that rattles have been found throughout the Fertile Crescent, most often made with handles that make them easier to shake. Since the fragments’ functions were not initially recognized, many other handles may have been found nearby and dispersed to other collections.

It’s thought that 4,000 years ago these may have had a dual use, for example to ward off evil spirits, with some from other sites made in the shapes of animals.

“The fact that toys were made locally and used in this neighborhood suggests that the needs of children were looked after and catered for,” the authors note. The discovery of a workshop where rattles were made “suggests a degree of commodification of childcare not seen previously.”

The authors note the rattles appear after changes indicating a swift growth in the city’s population. The speculate this brought economic changes that probably led to more parents working outside the home than would have occurred previously, creating more of a need for older siblings left to do childcare to distract infants in parents’ absence.

“Perhaps a parent stopped at a market stand on their way home and bought a rattle as a present for their child. This scenario is entirely recognisable to us today,” Hald said.

The study is published in the journal Childhood in the Past.

[H/T: Phys.org]

Source Link: 4,000-Year-Old Syrian Baby Rattles Look Surprisingly Familiar