The earliest evidence of wine drinking in the Americas may have been found in the remnants of 15th-century ceramics. Discovered on a small Caribbean island, the sherds also tell a tale of changing culinary traditions of the area in the wake of Spanish colonialism.

In a paper detailing their findings, researchers describe 40 pottery fragments found on Isla de Mona and examined them using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry, making this the first study to use molecular analysis methods on 15th-century ceramics from the Puerto Rico region.

Among these fragments were those from a Spanish olive jar dated between 1490-1520 CE – around the time Columbus first noticed the island – and containing residues of wine. Such jars were used in Europe at that time to store food and liquid goods.

The remnants of the jar provide the earliest molecular evidence of wine in the Americas we have to date, and the authors have good reason to believe that the imported wine was consumed on the island: the jar was discovered inside a cave, near a bell that may have been used in religious rites.

“Whether consumed by Europeans or members of the Indigenous population, this is direct evidence for the importation and drinking of European wine to a tiny island in the Caribbean shortly after the arrival of Spanish colonialists,” they write.

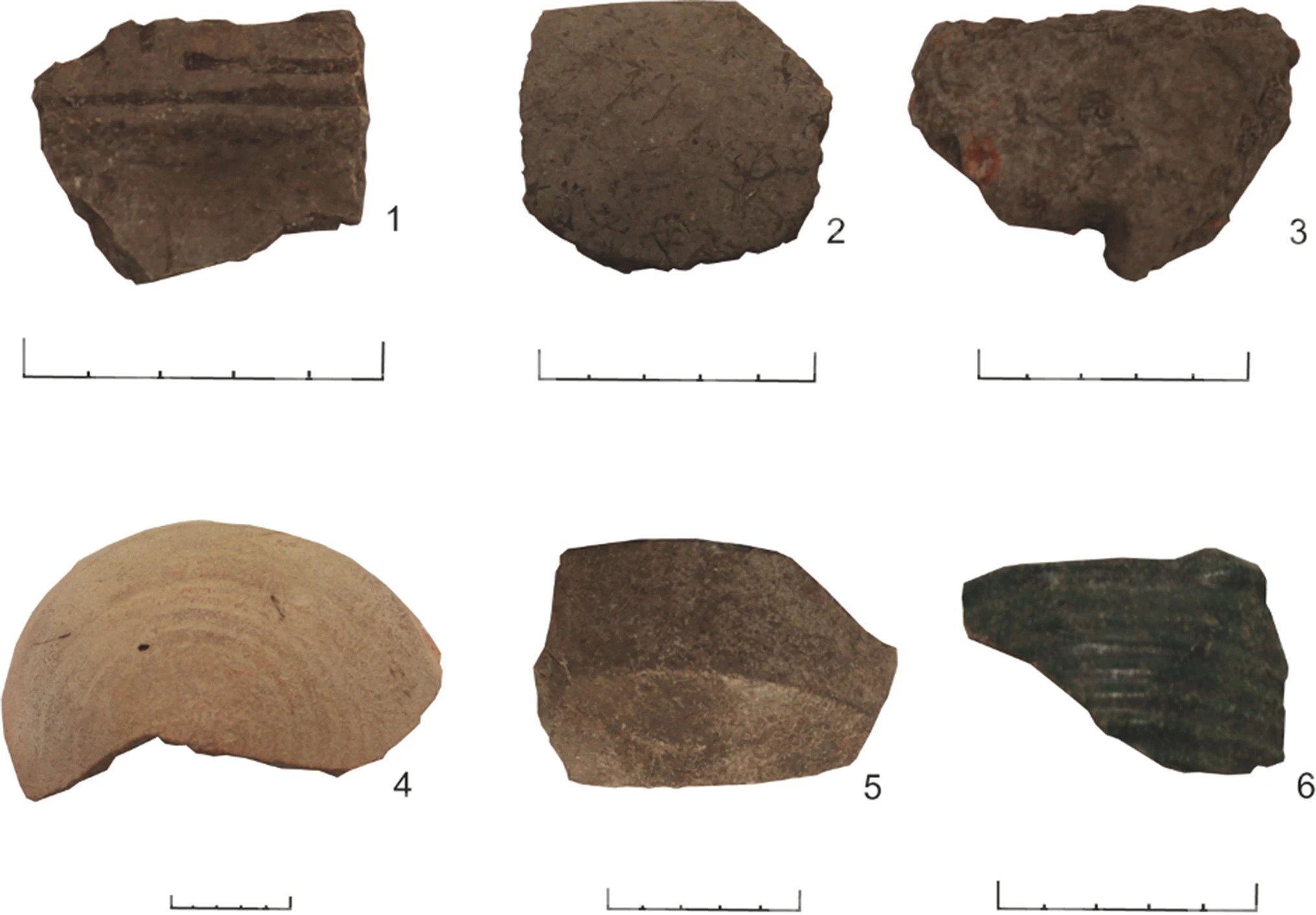

Ceramic samples from the six categories of pottery that were analyzed.

The analysis also offers an intriguing insight into culinary practices on the island. Despite finding plenty of fish bones scattered around the excavation site, no traces of animal residues were found in sherds of cooking pots.

“Put simply, it appears there was more than one way to cook a fish,” the researchers conclude.

In Europe, stews and casseroles were the preference, hence meat remnants are often found in cooking pots from there. On Isla de Mona, however, the research suggests, the Indigenous Taino people may have opted for spit-roasting, pit-roasting, or the use of a “barbacoa” (a large raised wooden grate, sort of like a barbeque) to cook fish. Vegetables, meanwhile, were cooked in ceramic pots. This would explain the absence of marine biomarkers among the remnants.

“It appears traditional foodways were maintained even after an influx of European colonialists arrived on the island with their glazed ceramics and olive jars,” writes the team.

There was also a distinct lack of dairy products – a staple of European cooking – in the cooking pots on Isla de Mona, further suggesting that Indigenous culinary traditions persisted in spite of, and were perhaps even adopted by, Spanish colonialists.

“Two culinary worlds collided in the Caribbean over 500 years ago, driven by the early Spanish colonial impositions. We really didn’t know much about the culinary heritage of this area and the influence of early colonialists on food traditions, so uncovering the discoveries have been really exciting,” lead author Dr Lisa Briggs said in a statement.

“The strong culinary traditions of the Taino people in creating the barbeque held firm despite Spanish colonialism, and influenced food right round the world. This continues today, as we are all familiar with a barbeque. I’m really pleased that this research shines a light on the cultural heritage of this community.”

The study is published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

Source Link: 500-Year-Old Ceramics Reveal Earliest Evidence Of Wine Drinking In The Americas