Drops of water found inside mineral deposits are the remnants of an ocean that disappeared 600 million years ago. Remarkably, the best place to find the minerals in question is kilometers above sea level. The scientists who found them say the droplets may explain a much-debated event crucial to life as we know it.

The discovery of marine fossils on the tops of mountains presented a major point of confusion to Renaissance and Enlightenment scientists. Eventually, the need to explain these findings contributed to our current understanding of how colliding tectonic plates can force up mountains, bringing once low-lying lands – and the fossils deposited there – with them. Along with the fossils, sometimes marine sedimentary rocks bring subtler treasures.

Around 650 million years ago, the Earth experienced one or more glaciations that made recent ice ages look puny. During these so-called Snowball Earth events, most (if not all) of the planet was covered in ice, and debate continues about how life survived at all. Soon after, however, came the great explosion in complex life forms that led to the diversity we see today, made possible by a big increase in atmospheric oxygen known as the Second Great Oxygenation Event.

The causes of this event remain debated, including whether it was connected to the preceding deep freeze, or if their association in time is a coincidence. To answer those questions, we need samples of deposits laid down at the time. Sometimes that means going to improbable places to find them.

In Uttarakhand, India, Indian Institute of Science PhD student Prakash Chandra Arya helped find calcium and magnesium carbonate deposits with water droplets inside. Based on the ages of the rocks in which these were found, Arya and teammates matched the water to the Snowball Earth era. “We have found a time capsule for paleo oceans,” Arya said in a statement.

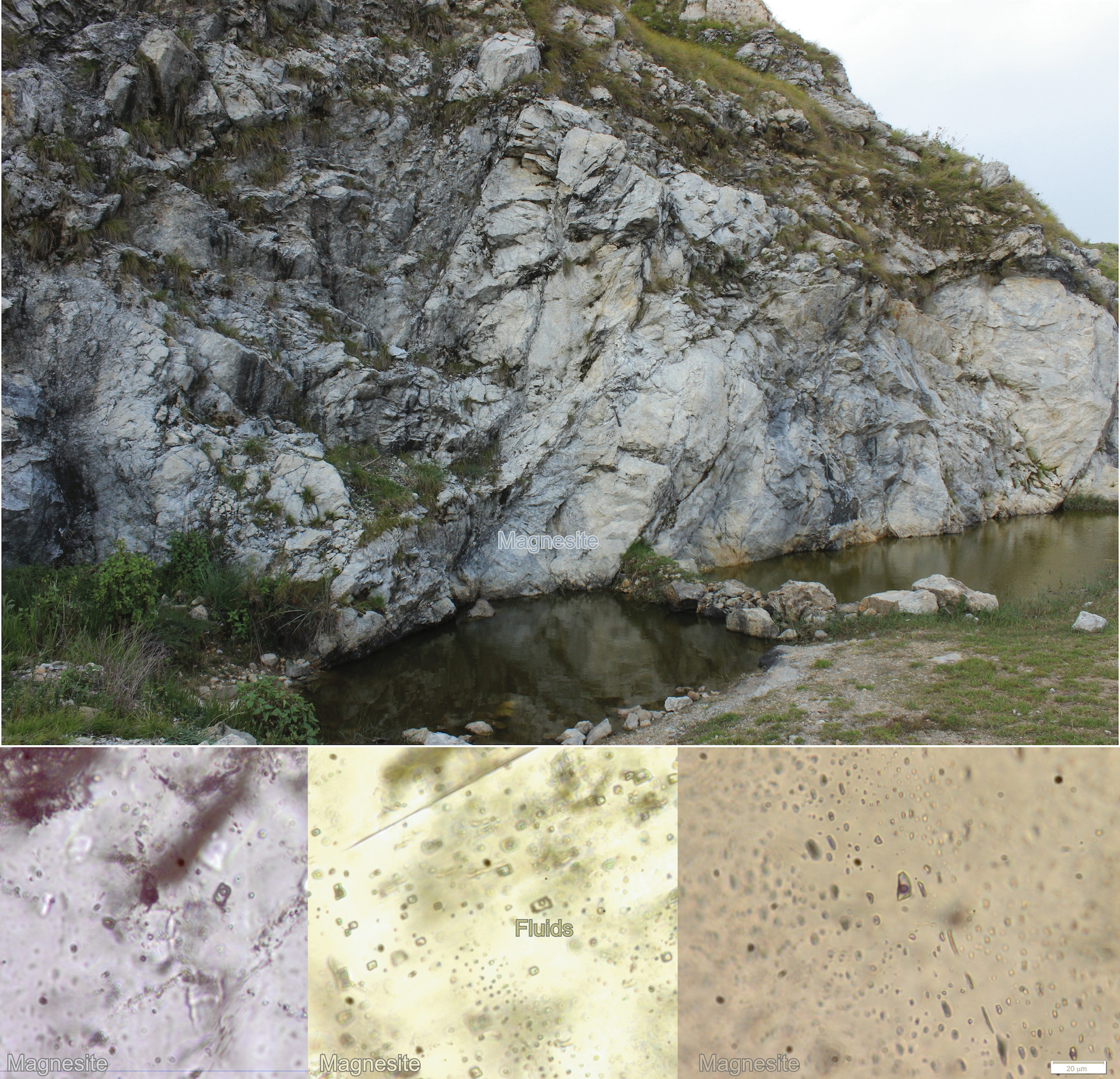

The outcrop and magnified images of magnetite with water droplets within it

Ima ge Credit: Prakash Chandra Arya

“We don’t know much about past oceans,” Arya continued. “How different or similar were they compared to present-day oceans? Were they more acidic or basic, nutrient-rich or deficient, warm or cold, and what was their chemical and isotopic composition.”

Himalayan deposits may not answer these questions for the whole world, but the team found a long period of diminished calcium supply, which they attribute to greatly reduced river flows into the sedimentary basin where the rocks formed. Locking so much water in ice leaves little to form rivers, although whether that is the reason remains to be seen. Rocks that would normally be mostly calcium carbonate have increased magnesium concentrations as a result. These magnesium carbonate crystals have pore spaces within them that trap water and have preserved it ever since.

The team points out that photosynthetic cyanobacterial stromatolites thrive in the nutrient-poor conditions associated with such calcium deficiency. When nutrients are more abundant, faster-growing species outcompete the stromatolites. As oxygen producers, the stromatolites may account for the Second Great Oxygenation Event, and animals’ subsequent rise.

Oceanic crust is usually recycled every 200 million years or so by being pushed beneath another plate. That’s removed most of the rocks laid down in marine environments during the Snowball Earth era. Of those that have survived, most either lack water-trapping pores or become chemically altered too easily to preserve records over such a long time. Himalayan magnesite is an exception – one precious enough that Arya and colleagues hunted it over large tracts of the Lesser Himalayas.

The study is published open access in the journal PreCambrian Research

Source Link: 600-Million-Year-Old Time Capsule Of Ancient Ocean Found In The Himalayas