Two large pterosaurs have been discovered in Afro-Arabia, including a new species that’s been named Inabtanin alarabia and had a 5-meter (16-foot) wingspan. The fossils were preserved in an unusually three-dimensional way, enabling scientists to establish how these giant flying reptiles got around between 66 and 72 million years ago.

The new species is a particularly exciting find as one of the most complete pterosaurs ever found in the region, and the other is a remarkably well preserved Arambourgiania philadelphiae that boasted a massive 10-meter (33-foot) wingspan. The specimens were retrieved from two different fossil sites that are the ancient remains of a nearshore environment on the margin of Afro-Arabia, an ancient landmass that encompassed Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.

A geographical landmark near one of the sites, known as Tal Inab (“grape hill), partly inspired the new species name, combined with the Arabic word tannin for dragon, which is a common theme in pterosaur etymology. Meanwhile, “Alarabia” is a hat-tip to the Arabian Peninsula.

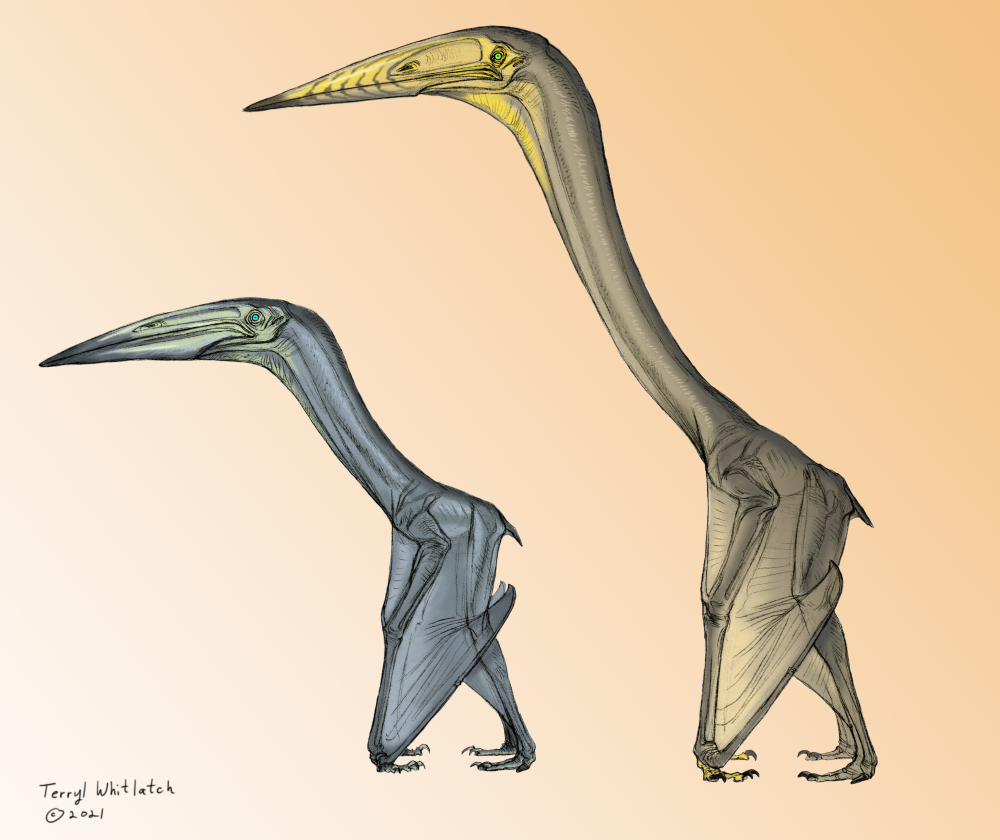

Inabtanin alarabia VS Arambourgiania philadelphiae, AKA, flapping VS soaring.

Image credit: Terryl Whitlatch

A new-to-science species is always an exciting find, but this one was particularly celebrated for the rare way in which it fossilized, giving us clues as to how the animal lived.

“The dig team was extremely surprised to find three-dimensionally preserved pterosaur bones, this is a very rare occurrence,” said lead author Dr Kierstin Rosenbach, from the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences of the University of Michigan, in a statement.

“Since pterosaur bones are hollow, they are very fragile and are more likely to be found flattened like a pancake, if they are preserved at all. With 3D preservation being so rare, we do not have a lot of information about what pterosaur bones look like on the inside, so I wanted to CT scan them.”

Doing so revealed the structure of its bones was very different to that of the A. philadelphiae, being more like those of modern-day flapping birds, while A. philadelphiae’s were vulture-like. And what are vultures famous for if not their knack for soaring around carrion?

“The struts found in Inabtanin were cool to see, though not unusual,” said Rosenbach. “The ridges in Arambourgiania were completely unexpected, we weren’t sure what we were seeing at first!”

Some pterosaurs flapped (top) while others soared.

Image credit: Terryl Whitlatch

What this tells us is that while some pterosaurs were flapping their way across the Cretaceous landscape, others were soaring, indicating their flight styles were more diverse than previously realized. As for what came first, the flap or the soar? It’s hard to say.

“There is such limited information on the internal bone structure of pterosaurs across time, it is difficult to say with certainty which flight style came first,” continued Rosenbach. “If we look to other flying vertebrate groups, birds and bats, we can see that flapping is by far the most common flight behavior.”

“Even birds that soar or glide require some flapping to get in the air and maintain flight. This leads me to believe that flapping flight is the default condition, and that the behavior of soaring would perhaps evolve later if it were advantageous for the pterosaur population in a specific environment; in this case the open ocean.”

The study is published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Source Link: 69-Million-Year-Old Pterosaur Is One Of The Most Complete Ever Found In Afro-Arabia