Harriet Cole’s body was taken to the Hahnemann Medical School’s anatomy department in 1888, where it’s believed that Rubus B Weaver then carried out a delicate and lengthy procedure to create a complete dissection of the human cerebro-spinal nervous system. It was celebrated within the academic community as an achievement for the insights it yielded for the field of neuroscience, but like much of human anatomy’s past, it was built on severely questionable practices surrounding informed consent and bodily autonomy.

To donate your body to medical science in the modern era, explicit informed consent is required before any institution can access and use your remains. In issue two of CURIOUS, we spoke to Professor Claire Smith, head of anatomy for Brighton & Sussex Medical School in the UK, about what actually happens to bodies donated to medical science. Smith explained that a signed consent form is often required before donated bodies can be processed today, but this hasn’t always been the case.

Perhaps one of the most illustrative examples of consent and the erasure of human identity in the study of anatomy is the case of Harriet Cole, a working class African-American who in death was remembered as an anatomical specimen rather than a person. It’s said that it took Weaver five months, amounting to over 900 hours of work, to extract the complete nervous system dissection from her body at Hahnemann Medical School.

Once complete, the anatomical specimen would become known as “Harriet”, but beyond that little of the alleged “donor” was remembered until decades later. It’s a sobering example of bodily autonomy being overlooked in pursuit of progressing academic understanding, but in recent years the brutality of removing a person’s identity in death is being increasingly recognized, both by those who house the remains to this day and researchers investigating Cole’s story.

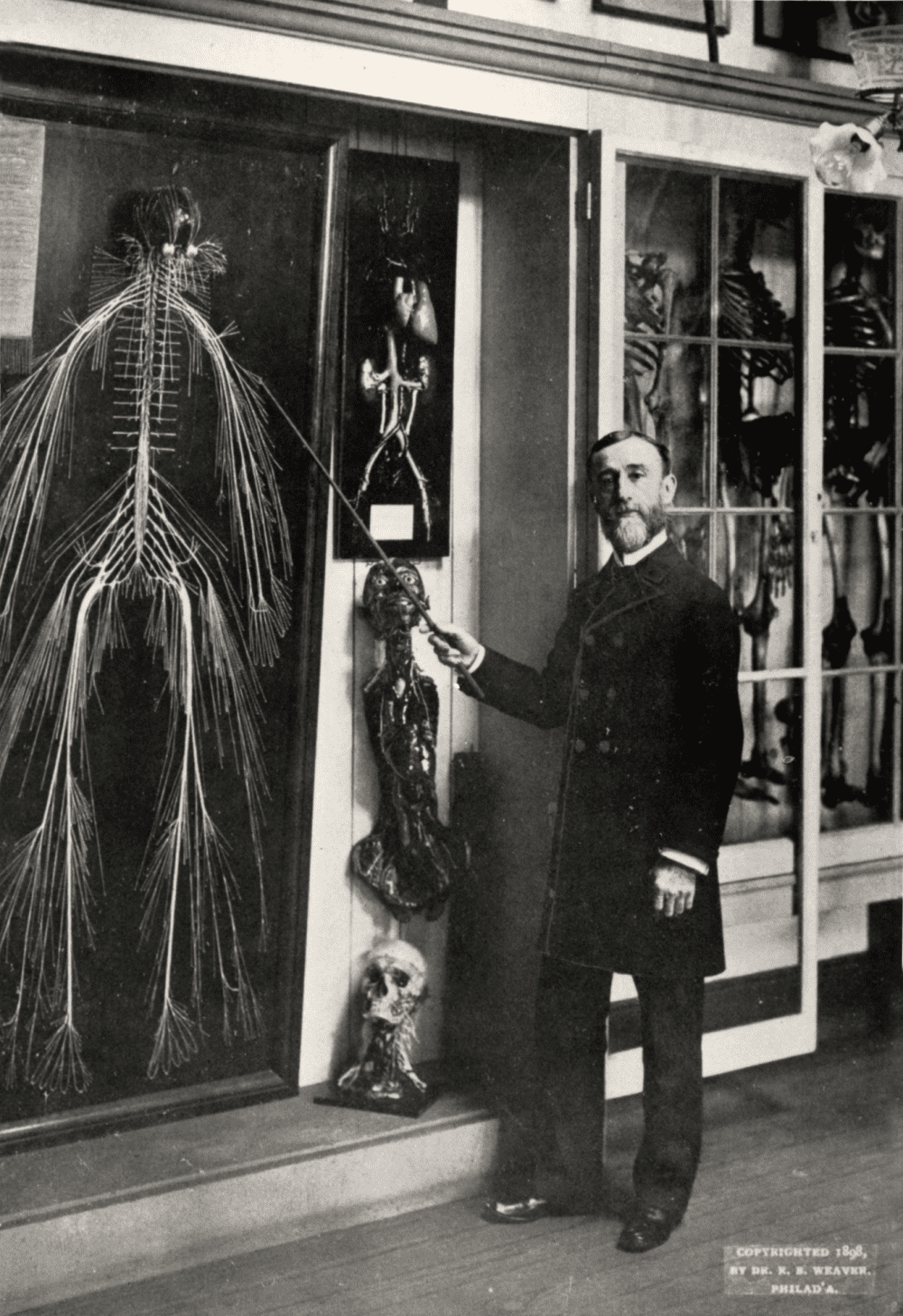

Rubus Weaver with “Harriet”. Image credit: Legacy Center Archives, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia.

“Initially anonymised, deracialised and unsexed, the central nervous system specimen endured for decades before her identity as a working-class woman of colour was reunited with her remains,” wrote Susan Lawrence and Susan Lederer in their 2023 paper Medical Specimens And The Erasure Of Racial Violence: The Case Of Harriet Cole.

It’s their view that alongside the remains of many people of color, Cole experienced a “kind of racialised medical violence that advanced medical knowledge, facilitated professional careers and encouraged the continuing exploitation of the bodies – living and dead – of people of colour in biomedical research and education.”

Informed consent has been a contentious topic surrounding the way in which Weaver’s work has historically been described, with initial reports dating back to the 1930s portraying the story of “Harriet” as one of donation in which Cole consented to having her remains handed over to science. However, it’s Lawrence and Lederer’s conclusion that “this is likely a confabulation that erased the history of violence to her autonomy and her dead body”.

That Cole “gifted” her remains to Weaver is just one of several inconsistencies in this complex story, one that archivists at Drexel’s College of Medicine Legacy Center in Pennsylvania have been working to untangle in recent years. Perhaps the biggest question of all being, is this dissection Harriet Cole at all?

“Initially anonymised, deracialised and unsexed, the central nervous system specimen endured for decades before her identity as a working-class woman of colour was reunited with her remains” – Lawrence and Lederer, 2023. Image credit: Legacy Center Archives, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia

“The facts that we actually have are, there is a record of a woman named Harriet Cole being treated at the Philadelphia General Hospital, which was a hospital of the courthouse here, and it shows her intake and coming and going from the hospital,” explained Margaret Graham, the director of Drexel’s College of Medicine Legacy Center’s Archives and Special Collections, to IFLScience.

“Then we have a death certificate that shows a woman named Harriet Cole’s body was transferred to Hahnemann Medical College in March of 1888, and that aligns with the articles that were then written about the nervous system dissection creation. Those are essentially the things that we have. You could say that’s not 100 percent, and because we’re archivists and we rely on documentation, there’s some possibility that the body that is documented on the death certificate is not the body that the anatomist actually used.”

Working with archival evidence in this way means that it is nearly impossible to know with absolute certainty the chain of events that led to the nervous system dissection’s creation, but at time of writing Graham says Drexel is approaching the story with the presumption that Cole’s body is the one from which the dissection was prepared.

To this day, Cole’s nervous system dissection is kept at the Legacy Center in Drexel, where Graham’s colleague and fellow archivist Matt Herbison has been able to lead important discussions surrounding its acquisition and history to visiting students.

The evidence archivists have to work with indicates the anatomical specimen was most likely taken from the body of Harriet Cole, but we can’t know for absolute certain. Image credit: Legacy Center Archives, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia

“There is definitely something about this specimen that people will react to in a very curious sort of way,” he told IFLScience. “[It means] we can talk about how the specimen was created and acquired as well as issues of consent and bodily autonomy.”

“The [human likeness] of this specimen is a huge part of people being open and willing to have those discussions. It’s very different than looking at a flat diagram in a book. It’s real, [and] experiencing going to a museum to deal and work with something real [is more impactful] as opposed to talking about something that’s real, but abstract and removed.”

Stories like Cole’s make for uncomfortable reading, but the work that archivists like those at Drexel do in helping to build a more accurate and complete picture of the history of science and anatomy can contribute to building a better future where mistakes of the past aren’t forgotten. There’s nothing that can be done about the way Cole’s remains were treated over 130 years after the fact, but giving anatomical specimens a personhood remains an invaluable endeavor.

Source Link: A 130-Year-Old Dissection Of The Human Nervous System Hangs In Pennsylvania