A 31,000-year-old skeleton discovered in Borneo appears to have undergone a surgical amputation of its left foot. While Stone Age surgery sounds like an extremely dicey move, it looks like the young hunter-gatherer recovered and lived for a number of years after the operation.

Reported in the journal Nature today, this find is the earliest evidence of advanced surgery ever seen in the world, predating other early operations found by tens of thousands of years.

An international team of researchers report the discovery of the young person’s skeleton, probably a child, buried in the Liang Tebo cave within the Indonesian portion of Borneo, an area known for its exceptionally early (and beautiful) displays of prehistoric rock art.

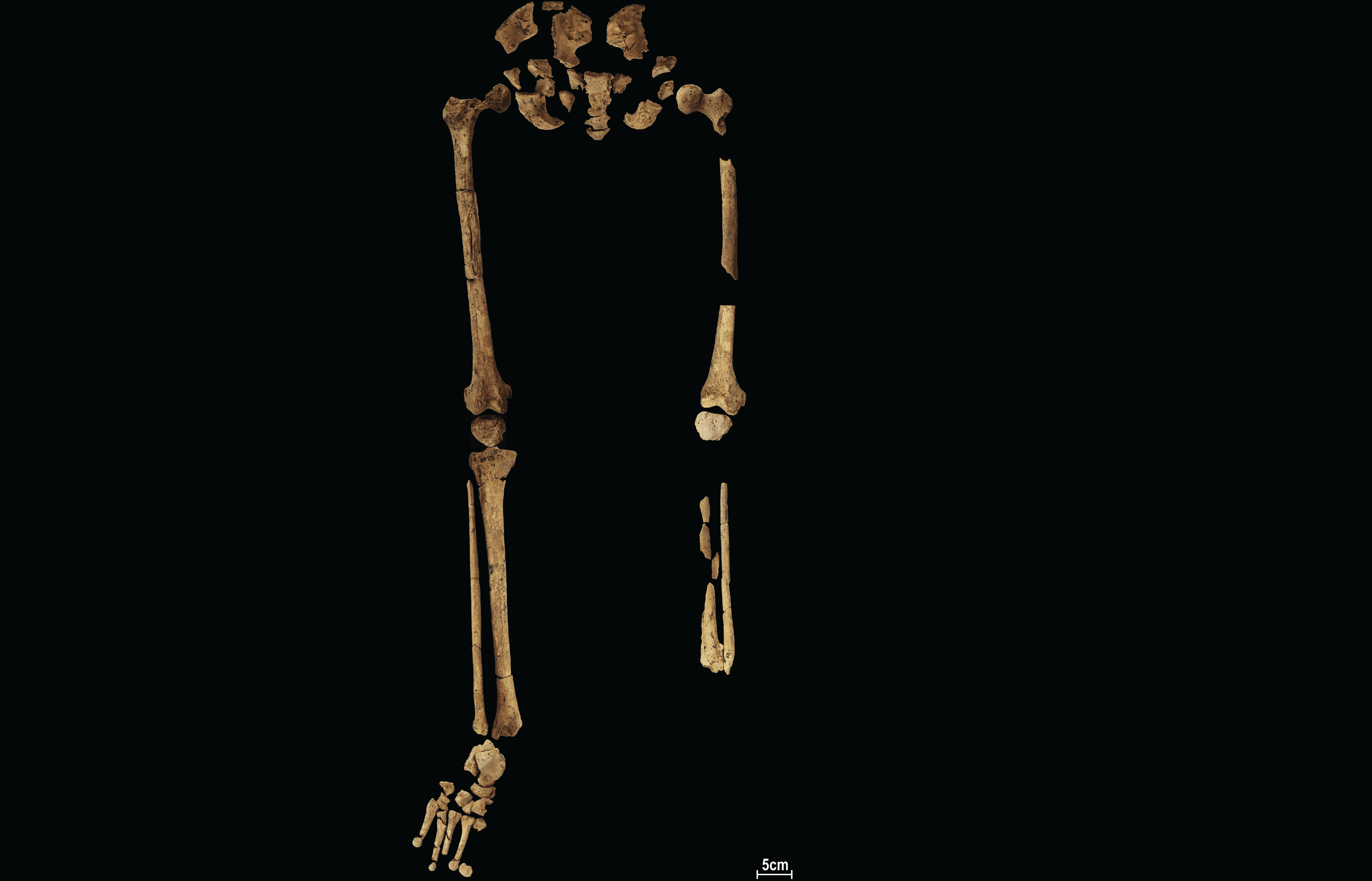

The remains of a young hunter-gatherer whose lower left leg was amputated. Image credit: Tim Maloney

The team quickly noted that the individual, dated to approximately 31,000 years ago, was missing the bottom third of their left leg. A closer look at the tibia and fibula revealed tell-tale bony growths that showed the bones were healing, bearing strong clinical similarities to bones that have been surgically amputated.

Most astonishingly, the bone shows no evidence of infection and indicates that the child survived and thrived for another six to nine years after the amputation.

The discovery has some huge implications. Firstly, it shows that this hunter-gatherer society possessed detailed knowledge of limb structure, muscles, and blood vessels to prevent fatal blood loss and infection. It also implies that these prehistoric peoples used antiseptic and antimicrobial agents to control potential infections – and did so with great success.

Prior to this new discovery, the oldest known example of a successful amputation comes from a Neolithic farmer in France about 7,000 years ago whose left forearm had been surgically removed.

It was previously assumed that humans must have been part of settled agricultural societies before they could explore the risky field of advanced surgery, but this new evidence challenges that assumption. It’s also worth considering how Western medicine only fully got to grips with antiseptics and complex surgery in the 19th century.

“For comparison, all of our pre-existing archeological cases for advance surgical procedures had all been associated with large settled agricultural societies: ancient Egyptians, Peruvians [etc]…” Dr Tim Maloney, lead study author from the Centre for Social & Cultural Research at Griffith Unversity, said in a press conference.

“Surviving amputation is a recent medical norm for most Western societies where antiseptics developed towards the end of the 19th century. That was the first major step towards amputations – often, at that time, conducted by barbers – not being a guaranteed death sentence,” Maloney added.

The dating of this discovery is astonishing, but perhaps it’s no surprise that this early medical knowledge managed to take root in Borneo, the researchers argue.

Found in the hot and humid tropics, this vast Asian island is bursting with life: some helpful to humans, some harmful. Although the soil of this land would be rife with nasty pathogens that could lead to debilitating infections, it also hosted a rich botanical variety from which medicines could be gathered.

This combination, they suggest, may have provided the perfect catalyst for these bold early forays into surgery.

“One possibility is that rapid rates of infection in the hot and humid tropics prompted early foragers in this region to tap into the rainforests’ ‘natural pharmacy’ of medicinal plants, leading to an early flourishing in the use of botanical resources for anesthetics, antiseptics, and other wound-healing treatments,” said Dr India Ella Dilkes-Hall from the University of Western Australia.

Source Link: A 31,000-Year-Old Leg Amputation Is The World's Oldest By A Long Shot