A team of physicists exploring an old and outdated model of the atom believes that it could help solve one of the most basic questions about our universe: why it exists at all.

In 1867, British physicist, mathematician, and engineer William Thompson (better known as Lord Kelvin) attempted to explain why there is an abundance of atoms in the universe, but they came in such few varieties. Lord Kelvin was working with a lot less knowledge than we have today. The luminiferous aether was a popular idea at the time, a hypothetical fluid thought to fill all of space, and the electron had not yet been discovered.

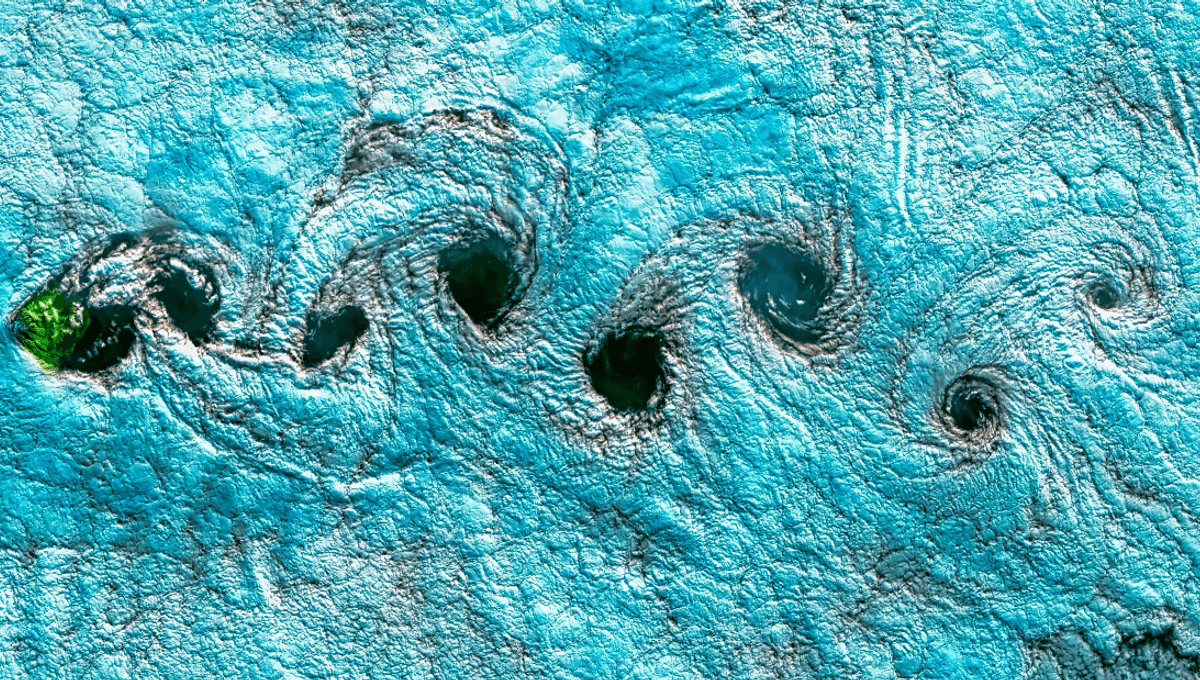

The idea Kelvin came up with was that what we think of as matter or atoms was in fact stable vortices in the aether. Just like a vortex can be semi-stable in fluids, and can be much more stable in superfluids and Bose-Einstein condensates (though Kelvin wouldn’t have known that), he suggested that atoms could be stable vortices in the aether, and the different elements are the result of these aether vortices becoming knotted in different ways.

This model of the atom was influential, but was ultimately shown to be incorrect thanks to the Michelson-Morley experiment, which ruled out the aether.

“Even though Kelvin’s idea failed to explain the most fundamental aspects of nature, the concept of knots has found extensive applications in various domains,” the team behind the new study explained in a 2024 preprint.

“One of the characteristics of knots is their topological nature; knots do not disappear unless the strings break or intersect, which has played a crucial role in persistent phenomena. For instance, knots appear as vortex knots or topological solitons called Hopfions in diverse subjects such as fluid dynamics, superconductors, Bose-Einstein condensates, 3He superfluids, nematic liquid crystals, colloids, magnets, optics, electromagnetism, and active matter. The stability of the solitons is ensured by the topological invariant associated with knots.”

In the new work, the team of physicists suggest that within the standard model “cosmic knots” could have formed in the very early universe, dominating it for a time.

“This study addresses one of the most fundamental mysteries in physics: why our universe is made of matter and not antimatter,” study corresponding author Muneto Nitta, professor at Hiroshima University’s International Institute for Sustainability with Knotted Chiral Meta Matter, said in a statement. “This question is important because it touches directly on why stars, galaxies, and we ourselves exist at all.”

During the Big Bang, according to our best models of the universe, matter and antimatter should have been produced in equal amounts. Since antimatter and matter annihilate when they meet (producing a huge amount of energy and other particles like neutrinos) this would have left an empty universe, devoid of matter or antimatter.

That isn’t the case, and the reason why the universe produced more matter (just one extra particle of matter for every billion antimatter-matter pairs) remains one of the biggest problems in physics. Current models simply cannot account for it. According to the new study, knotted solitons in the early universe could be the answer.

“[W]e present the first theoretical demonstration of stable knot solitons emerging within a particle physics framework,” the team writes in their paper.

“Specifically, we consider a simple model incorporating both global and local 𝑈(1) symmetries, which can be identified with the Peccei-Quinn 𝑈(1) symmetry [42,43] and the 𝐵 −𝐿 (baryon number minus lepton number) symmetry, respectively. The spontaneous breaking of these symmetries gives rise to two distinct types of stringlike topological defects: flux tubes (local strings) and superfluid vortices (global strings). We find that when these two types of strings are linked together, they form stable knot solitons.”

The team suggests that during the early universe, these symmetries fluctuated and broke. In the mess, threadlike cosmic strings eventually formed metastable knot solitons that came to dominate the universe for a time. Eventually though, these knots would untangle through quantum tunneling and produce heavy right-handed neutrinos, a result of the B–L symmetry in their structure, which then decay into more stable matter with an ever-so-slight favor towards matter over antimatter.

“Basically, this collapse produces a lot of particles, including the right-handed neutrinos, the scalar bosons, and the gauge boson, like a shower,” Yu Hamada of the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron in Germany explained. “Among them, the right-handed neutrinos are special because their decay can naturally generate the imbalance between matter and antimatter. These heavy neutrinos decay into lighter particles, such as electrons and photons, creating a secondary cascade that reheats the universe.”

“In this sense,” Hamada added, “they are the parents of all matter in the universe today, including our own bodies, while the knots can be thought of as our grandparents.”

Using this model, the team claims that they may be able to clear up a few other cosmic mysteries, such as the strong CP problem, dark matter, and neutrino masses. However, it is still at an early stage, and it could be some time before we have evidence to support or refute the idea.

“The next step is to refine theoretical models and simulations to better predict the formation and decay of these knots, and to connect their signatures with observational signals,” Nitta added. “In particular, upcoming gravitational-wave experiments such as LISA, Cosmic Explorer, and DECIGO will be able to test whether the Universe really passed through a knot-dominated era.”

The study is published in Physical Review Letters.

Source Link: A Forgotten 19th Century "Vortex" Model Of The Atom May Help Explain Why The Universe Exists At All