As an undergraduate at the University of New South Wales, Dr Erica Barlow picked up a rock that would change her life, and quite possibly how we see the history of life on Earth. It took a long time to work out what she had, however, and even today no one can be sure the rock contains what Barlow and others suspect.

Barlow was in Western Australia’s Pilbara region to study stromatolites, some of the oldest fossils we know. The trip involved many long walks between the campsite and the fossils; on one journey back Barlow noticed a shiny black rock catching the setting Sun against the region’s famous red dirt. She picked it up as a reminder of the trip. “I kept it on my desk as a kind of pet rock while I wrote my [honors] thesis,” Barlow said in a statement.

Barlow was still working on stromatolites when her supervisor, Martin Van Kranendonk, noticed the rock and identified it as black chert. Kranendonk told her black chert has been known to hold microfossils from early in life’s development on Earth, (although this is debated) and suggested she check it out. Buried in her thesis, Barlow needed some encouragement to take the time to prepare and examine a sample, but was astonished when she did.

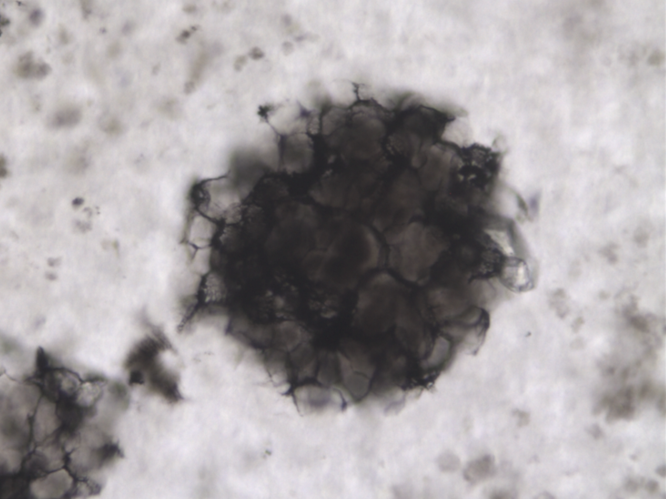

One of the specimens Barlow found showing some of the complexity.

Image credit: Erica Barlow

Fossils in the chert looked like nothing Barlow had seen before. Moreover, no one else had seen anything like them either. Given the chert’s age, if there were any microfossils inside they were expected to be of single-celled organisms. The microfossils Barlow had found look more like a soccer ball: almost round, but with a complex outline and an internal honeycomb structure.

“There was nothing else like the microfossil I found in the geological record,” Barlow said.

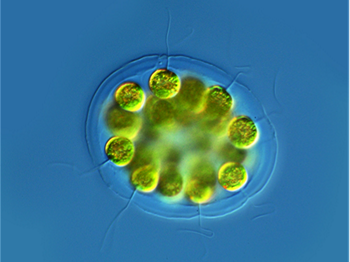

The closest living analog for what Barlow found appears to be certain algae, such as this sample of Volvocacean coenobial, showing hollow structures surrounded by hair-like flagella, which are both encircled by a thick, gum-like substance called mucilage.

Image credit: Antonio Guillén

That’s a big claim under any circumstances, but considerably bigger when the chert was thought to date back long before complex life was thought to have appeared.

The stromatolites Barlow had been studying involve thousands of cells that collectively form layered structures out of their own bodies and sand. However, they are not what we consider complex life.

As far as anyone knew, the first complex life forms were hundreds of millions of years younger than this discovery. Barlow’s find might be a predecessor of the eukaryotes, the branch of the tree of life that includes all animals, plants, fungi, and algae. Or it might be an evolutionary dead-end, an early flowering of complexity that was snuffed out. Then again, it might be just an illusion, mimicking complexity in some way we can’t explain.

There was only one thing for it – make the rock the subject of her PhD.

First Barlow needed to know if the chert was unique. Returning to the collection site answered that almost immediately. Barlow found a rock wall dotted with thousands of black chert nodules 30 meters (100 feet) up a nearby slope. Like the Pilbara itself, the wall stretched out of view in both directions. Barlow told IFLScience she has since measured the formation at 12 kilometers (7 miles) long, all laden with chert nodules averaging 20 centimeters (8 inches) wide and 7 centimeters (3 inches) high.

It’s a thin line through the vastness of the Pilbara, but the chert-containing formation stretches out of view.

Image credit: Erica Barlow

Many chert samples appear to contain no fossils at all. Others hold organisms that look like those found worldwide from this time – “either long thin filaments or unicells – like bubbles,” Barlow told IFLScience. A scientist who collected a small sample could easily go home thinking there was nothing unusual.

Aware of the potential significance of her discovery, however, and the need to replicate it, Barlow collected hundreds of samples. Back in Sydney she found several contained specimens resembling her original, with some even having amber spheres within the honeycomb shapes. She has now expanded the specimens to 19, including half a dozen from a single rock. Barlow’s hundreds of samples also contain some that might have originally looked similar, but are too degraded for her to be sure. If she’d picked up one of these instead, she would probably not have recognized its value.

The formation is not primarily black chert, but the modules are not hard to find.

Image credit: Erica Barlow

The chert samples are clearly of the same age, and independent testing verified they all formed about 2.4 billion years ago. Crucially, that coincides with the date geologists have now settled on – after much debate – for the Great Oxidation Event. This is the point where oxygen levels in the atmosphere and the oceans grew so dramatically that it became possible to breathe, opening the door to complex life.

Previously there had been an unexplained gap of around 750 million years between oxygen becoming available and the first eukaryote fossils, demonstrating something was taking advantage of it.

Unfortunately, however, none of the specimens Barlow has found can be proven to be predecessors of eukaryotes.

“When you’re working with material from this time, it’s really hard to prove or disprove something like this, because we just don’t have enough information preserved,” Barlow said in the statement.

Geneticists date the timing of major advances in life using “molecular clocks”, but Barlow told IFLScience these produce “a huge range of estimates” for the time when eukaryotes emerged. Some of these are close to the age of her chert, but others are hundreds of millions of years later. “One problem is molecular clocks are informed by fossil record, which makes it a bit grey when you look back this far, where the fossil record is so patchy,” she said.

There are 6-700 million years represented by a handful of sites on the planet.

Dr Erica Barlow

Theoretically, chemical analysis might provide valuable evidence. “If we can identify the type of carbon, it might tell us what the organism ate,” she said, potentially proving its complexity. However, this is nearly impossible because samples are so easily contaminated with carbon from the modern world.

“Working with such tiny fossils, with so little carbon, if we got a positive result the [scientific] community would not believe it because of possibility of contamination,” Barlow told IFLScience.

Some future technology might improve the process, but in the meantime Barlow’s work has struggled to get recognition. The remoteness of the location might be part of the problem. When the oldest animals were found in the Ediacaran Hills in South Australia, many palaeobiologists refused to believe they were real until they saw them personally. The location made that a slow process.

If similar fossils were found elsewhere in the world it might help Barlow’s case, particularly if something somewhat later showed signs of further development. So far, nothing has turned up. Barlow admitted to IFLScience this could be the only evidence of an early experiment with complexity that was snuffed out, and did not reoccur for a long time.

On the other hand, the lack of another location is not entirely surprising given how few sites preserve fossils more than 1.6 billion years old. “There are 6-700 million years represented by a handful of sites on the planet,” Barlow told IFLScience. It’s not easy to preserve a fossil site, but Barlow thinks such an extreme shortage may be a consequence of the state of plate tectonics at the time.

If these specimens are ancestral eukaryotes, they wouldn’t have looked very exciting by modern standards. “From what we can tell, the life would have been soft, squishy and gooey – kind of like slime that you see at the edge of a pond,” Barlow said in the statement. Nevertheless, Van Kranendonk noted the similarity to modern eukaryotic algae,

While Barlow waits for something to break that could help us learn more about her discovery, she has completed a postdoc with NASA in the marvellously named Laboratory for Agnostic Biosignatures. There she tried to design ways to identify life on other worlds if it doesn’t look like Earth-life; she might have had about the best training that exists for such a task.

Barlow’s most recent study on the discovery is published open access in Geobiology.

Source Link: A Geobiologist Found Possibly The Oldest Complex Fossil – In Her Pet Rock