We humans love putting things in boxes. Assigning simple categories makes us feel comfortable – but all too often, biology comes along to ruin the fun. Sex is often described in simplistic, binary terms: male and female. The reality, however, contains a lot more shades of gray, and now a new study is showing that even when it comes to the organs in our bodies, binary sex categories are unhelpful.

According to the new paper, many organs in the human body are a mishmash of male and female characteristics. Some are more distinctly sex-specific, while some barely differ between the sexes. All in all, the authors conclude, “adult individuals are composed of a mosaic spectrum of sex characteristics in their somatic tissues that should not be cumulated into a simple binary classification.”

The researchers looked at mice from different lineages, including wild mice and house mice, and collected gene expression data across a range of organs and reproductive tissues: the heart, brain, kidney, liver, mammary tissue, ovary/testis, oviduct/epididymis, and uterus/vas deferens. They also compared their results with human genetic data from the GTEx Project.

As you might expect, male/female binary sex differences were most apparent in sex organs. As soon as you move away from that, however, the distinctions become a lot less clear.

In mice, for example, the kidneys and liver show large sex-specific differences, whereas in humans, adipose (fat) tissue has very different expression profiles between males and females. In both mice and humans, brains show only very minimal differences, something that’s been corroborated in other research.

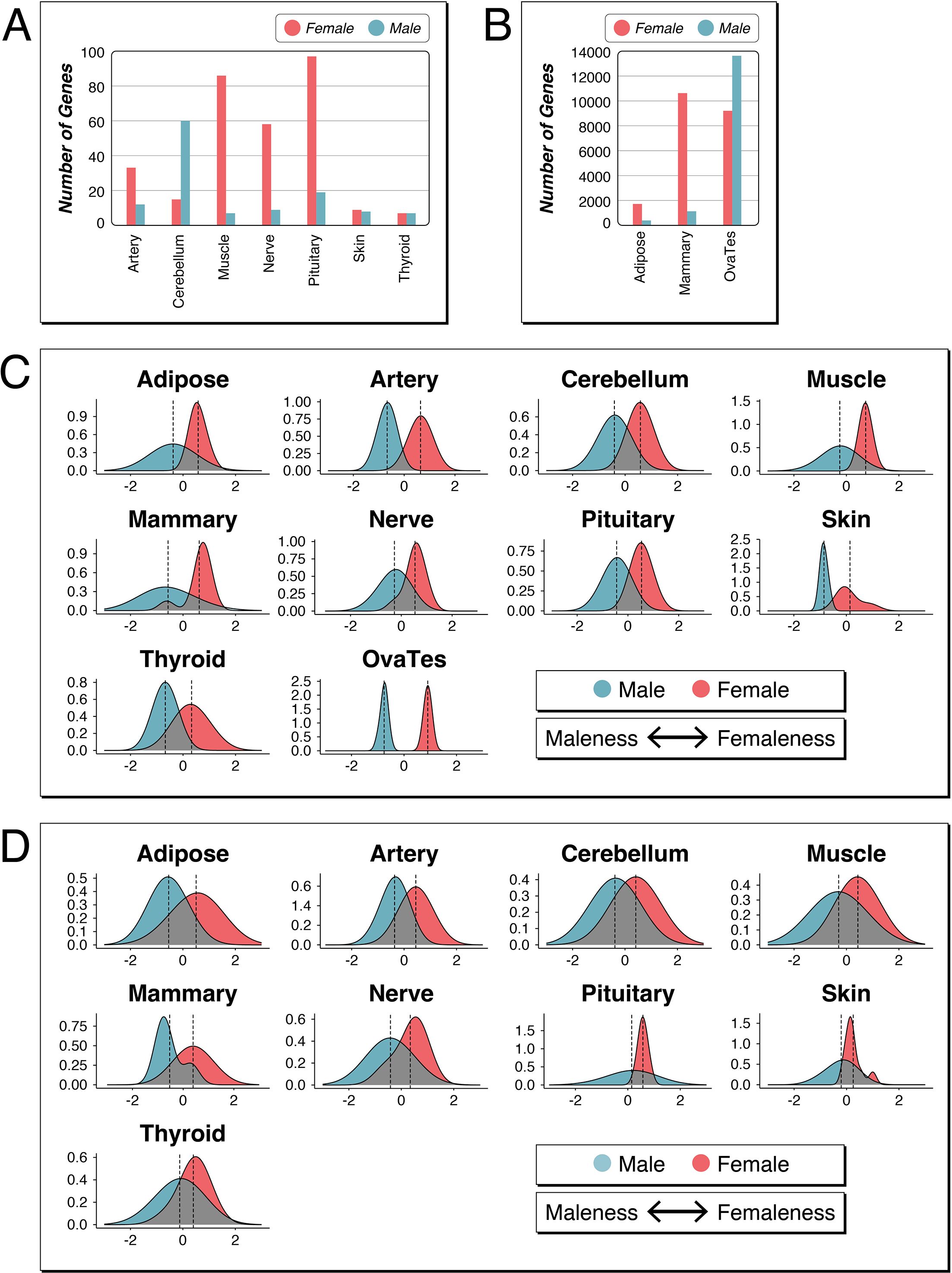

The team developed a Sex-Bias Index (SBI) to assign a value to summarize the “male and femaleness” of a particular organ. While they note in their paper that the concept of the SBI was criticized during peer review and therefore may merit further refinement, they say it is a way to “directly visualize these variance patterns in an intuitive way.”

The included species and subspecies of mice encompassed “an evolutionary distance of about 2 million years”, the authors explain. Yet even between these taxa, most of the genes they looked at had lost or switched their sex-specific roles, demonstrating how quickly this type of gene activity evolves. The genes were also not affected individually, but usually as networks of related genes that undergo evolutionary pressures together.

What that means for us in practice is that mice aren’t a great model if we want to study sex differences in humans.

In the human data, the overarching pattern was one of less sex specificity: there were fewer sex-specific genes and stronger male/female overlaps than in the mice, making the idea of a strict sex binary even less convincing.

“Sex is therefore not rigid and clear-cut, but shaped by evolution, overlaps and individual differences,” reads a statement on the study from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology.

It may not be the comforting boxes our brains look for, but in our view, the messy, complex reality is definitely more intriguing. And the editors assessing the paper agreed, calling the study a “fundamental advance” with “convincing evidence”.

The study is published in the journal eLife.

Source Link: “A Mosaic Spectrum Of Sex Characteristics”: Most Organs In Our Bodies Don’t Fit The Male-Female Sex Binary