Olo is described as a “new color” that scientists argue they’ve enabled people to see – one that doesn’t resemble anything in our everyday visual experience. It’s described as an intensely saturated greenish-blue, brought to life using a new technique that stimulates the eye’s photoreceptors in a non-conventional way.

“We name this new color ‘olo’,” the study authors write.

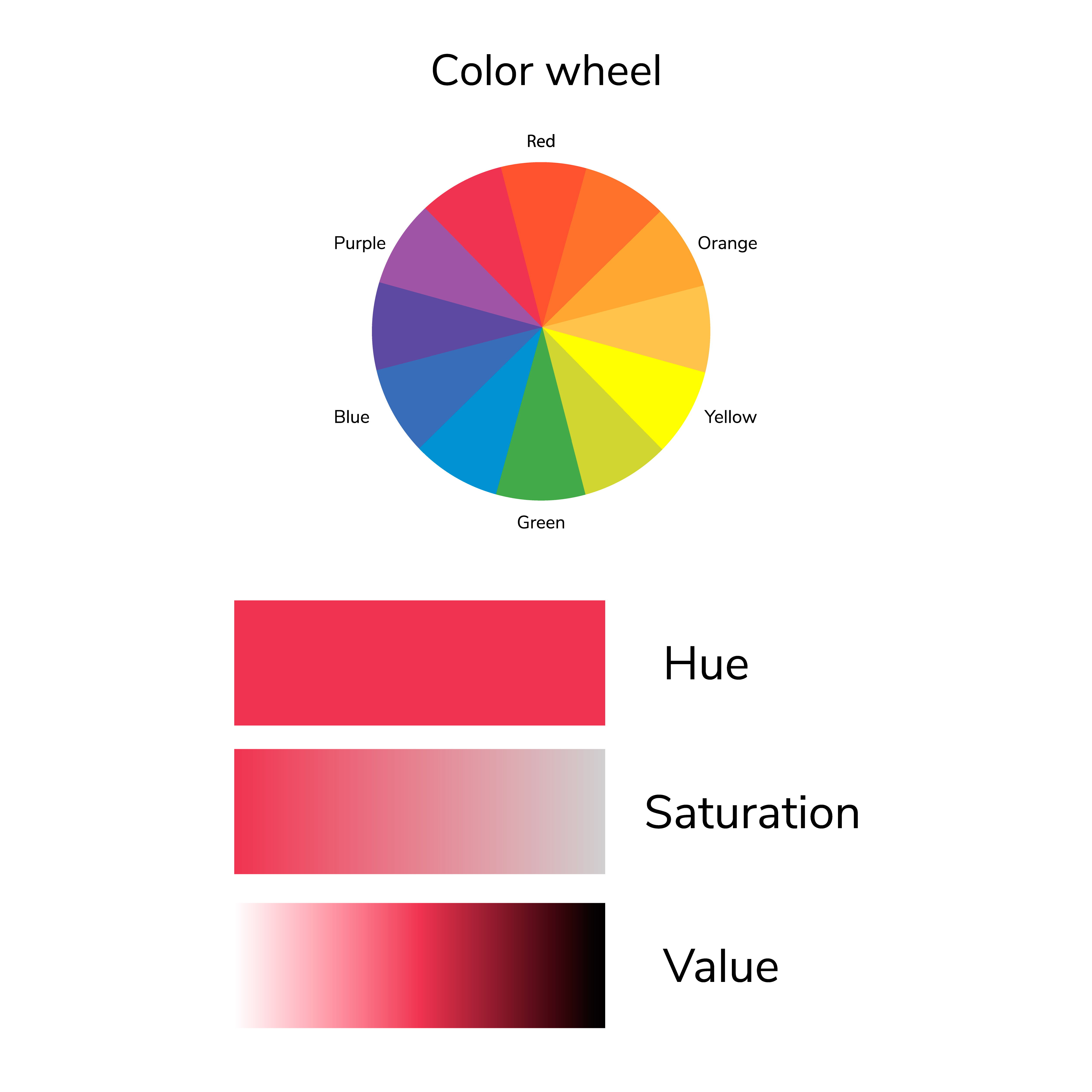

But can this really be considered a “novel color” like the researchers boldly claim? The three components of color are hue, saturation (or chroma), and value (or brightness). The study suggests olo appears with a uniquely strong saturation, but its hue remains firmly in the grasp of blue-green. Anyway, we’ll leave that debate for the color scientists and the comment section for now. Regardless of the definition, those who’ve seen olo say it offers a visual experience that’s subtly unfamiliar.

“Subjects report that olo in our prototype system appears blue-green of unprecedented saturation, when viewed relative to a neutral gray background. Subjects find that they must desaturate olo by adding white light before they can achieve a color match with the closest monochromatic light, which lies on the boundary of the gamut, unequivocal proof that olo lies beyond the gamut,” they added.

“Color names volunteered for olo include ‘teal,’ ‘green,’ ‘blue-greenish,’ and ‘green, a little blue.’ Subjects consistently rate olo’s saturation as 4 of 4, compared to an average rating of 2.9 for the near-monochromatic colors of matching hue,” it continues.

With red as an example, this diagram shows the three components of color: hue, saturation (or chroma), and value (or brightness).

Image credit: Sandy Storm/Shutterstock.com

Color is a perception that we experience when certain wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation stimulate the cone cells in our retina, sending signals to the brain. Coating the back of our eyeball, we have three types of cone photoreceptors: short-wavelength (S), middle-wavelength (M), and long-wavelength (L), each with overlapping spectral sensitivities.

Because of this overlap, any given light wavelength stimulates at least two types of cones simultaneously, which limits the range and saturation of colors that we can perceive.

In a new study, scientists at the University of California, Berkeley have developed a way to directly stimulate a single cone by blasting it with a focused laser light, called Oz. Using this system on five human subjects, the laser system was able to solely trigger M cone cell activity, leading people to report experiencing a color described as “blue-green of unprecedented saturation.”

Furthermore, they were able to wield this technique to stimulate thousands of individual cones, allowing them to create images and visuals with the technique.

Traditional color technologies – like the computer screen you’re currently looking at – rely on a method called spectral metamerism. This involves blending different wavelengths of light to mimic the way our eyes perceive specific colors, prompting the cone cells in our retinas and our brains into seeing a match. This strategy has been around since at least 1861, when James Clerk Maxwell wowed audiences at the Royal Institution by layering red, green, and blue images to create full-color visuals.

The Oz method uses a different approach. Rather than adjusting the spectrum of light, it controls the spatial distribution of light on the retina, a concept known as spatial metamerism. This allows for the creation of a broad range of colors using a single monochromatic light, sidestepping the need for the three light primaries.

Commenting on the new study, experts acknowledge that while the research introduces some promising practical innovations, some aspects of single-cone stimulation are not entirely new.

“When only M cone is stimulated, observers report that they see an unusually saturated greenish blue. Normally, focussed on retina point source, such as a star, excites several cones due optical constraints. To overcome this, adaptive optics is used, a method that astronomists use to look at stars. Single cone stimulation was known earlier. The novelty of this paper is that they use this method to stimulate many individual cones and produce an image,” Dr Misha Corobyew, Senior Lecturer in Optometry and Vision Science at The University of Auckland – who wasn’t involved in the new study – said in a statement.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.

Source Link: A "New Color?" Scientists Claim "Olo" Is Like Nothing You've Ever Seen Before