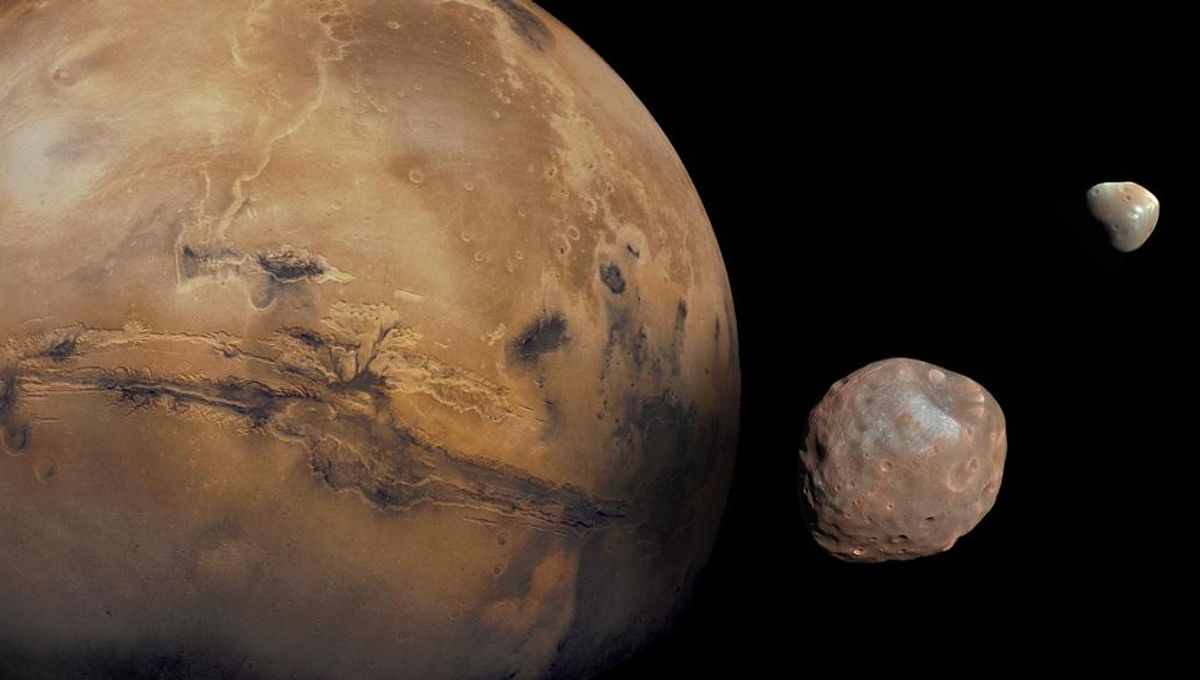

The Martian moons Phobos and Deimos may be remnants of an asteroid that got too close to Mars and was destroyed by its gravity. The explanation, backed by supercomputer simulations, could resolve a long-standing debate between two options, both with substantial flaws.

The existence of Phobos and Deimos has puzzled astronomers for a long time, and the closer anyone looks the more confusing the pair have become. According to one explanation, the pair are asteroids captured by Martian gravity. According to another, they’re composed of material thrown up when a larger asteroid hit Mars, like a smaller version of the process that is thought to have created our own Moon. Unfortunately, each account explains opposing halves of what we think we know about Deimos.

Dr Jacob Kegerreis of NASA’s Ames Research Center leads a team that proposes a larger asteroid got so close to Mars the gravitational effects destroyed it, and Phobos and Deimos formed from some of the wreckage. Ames is based in Silicon Valley, and Kegerreis and co-authors seem to have adopted some of the language, saying the asteroid was “disrupted”, a euphemism that in this case might rank with “collateral damage”.

The idea is immediately appealing because it deals with the major problems of each preceding origin tale. Phobos and Deimos appear to be composed of material that is much more like asteroids than Martian crust, which doesn’t make sense if they were blasted off the Red Planet’s surface. On the other hand, their orbits are highly circular and aligned with the equator, which is very unusual for captured objects.

If an asteroid was torn apart above Mars, the smaller objects that formed from the remnants would have the right composition, and also might well have circular orbits. After all, the rest of the material, that didn’t make it into such stable orbits would either have landed on Mars or eventually escaped the system.

Neat as this seems, answers that seem to combine the best of both worlds often have problems of their own. Kegerreis and co-authors conducted extensive modeling to see if a suitably sized asteroid would be “disrupted” in this way, and produce an outcome like we see.

They found the idea plausible. The majority of fragments would leave the system over astronomical timescales, but if the asteroid was about half the mass of Vesta that would leave enough for what remained to form the two moons.

Initially, moderately sized debris pieces would have crashed into each other in a natural version of the Kessler Syndrome. This would have become a disk that might have looked a little like Saturn’s rings. Early collisions would have taken place at high relative speeds, causing bits to break apart.

However, once the slow influence of gravitational forces brought objects into similar orbits, the pieces would start to stick together when they encountered each other, because their motions were so similar. Gradually the disk would coalesce into a small number of Moons. Phobos is slowly migrating inwards towards Mars, and will eventually crash into it, while Deimos is going the other way. They presumably formed much closer together, but if a third moon formed closer in than Phobos, it would have been destroyed by now, while one beyond Deimos may have eventually wandered off.

The simulations show that such a scenario is plausible for a variety of initial conditions in terms of the destroyed asteroid’s mass, speed, closest approach to Mars and spin, the last of which turns out to be surprisingly important. The closer to Mars the asteroid came, the more of it would have been captured into disks, and therefore the smaller it could have initially been.

“It’s exciting to explore a new option for the making of Phobos and Deimos – the only moons in our Solar System that orbit a rocky planet besides Earth’s,” said Kegerreis in a statement. “Furthermore, this new model makes different predictions about the moons’ properties that can be tested against the standard ideas for this key event in Mars’ history.”

The original asteroid in this scenario can also be quite a lot smaller than the one required to provide a debris disk in the case of a collision. Since medium-sized asteroids are more common than very large ones, that also makes the scenario more likely.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA’s) 2026 Martian Moons eXploration (MMX)mission will give us a much more detailed idea of the moons’ composition, particularly Phobos. Analysis of either moon should settle the possibility of the impactor hypothesis. If Kegerreis and colleagues are right, the two moons should also be more similar in composition than we would expect if they’re two independently captured asteroids. However, under some scenarios, a larger moon initially formed out of the disk, before crashing into Mars and throwing up a new disk that became Phobos, in which case the inner moon should mix asteroid and Martian material.

The team plan to spend the time until MMX reaches the moons making more detailed predictions of how Phobos is made up, which will be tested against what the mission finds when it arrives.

The study is published in the journal Icarus.

Source Link: A New Explanation Offered For The Origins Of Mars’s Moons