The great thing about science is that it’s constantly evolving. What was once common knowledge is now a (hopefully ironic) meme; diseases that once wiped out whole families quite literally no longer exist; and time and time again, we have found that everything we thought we knew about the course of history is, in fact, wrong.

It’s in this spirit, then, that a new study from researchers at the Australian National University in Canberra and the Natural History Museum of London should be received – because it is, quite frankly, about to shake up the whole gosh-darn story of human evolution.

And all it took was a second look at some old fossils.

The problems with radiometry

There are many ways to date ancient finds – dendrochronology, for example, uses the growth of trees to figure out when sites were active – but one of the more famous ones is radiocarbon dating. It’s based on nuclear physics, of all things: it dates a site by analyzing the amount of carbon-14 left in organic remains like bones or charcoal.

While organisms are alive – everything from a tardigrade to a T. Rex – their tissue absorbs carbon-14 isotopes. They’re unavoidable; they rain down on us from all directions as a result of cosmic rays interacting with the Earth’s atmosphere.

It’s only once an organism dies that this absorption stops – and it’s then that something interesting starts happening. Carbon-14 isn’t just any isotope: it’s the only naturally occurring version of carbon that is radioactive, and it has a half-life of around 5,730 years. That means that an artifact from, say, ancient Mesopotamia will have roughly half as many carbon-14 isotopes as it did originally – the rest will have decayed into nitrogen. So, by measuring the ratio of one element to the other, scientists can pinpoint the approximate age of the find.

It’s undoubtedly ingenious, but here’s the problem: far from being the slam-dunk technique it’s sometimes portrayed as, radiocarbon dating is only effective on fossils younger than about 50,000 years. That’s why we don’t use it to date dinosaur bones, for instance: to take our old friend T. Rex, who lived something like 70 million years ago, as an example, the amount of carbon-14 left would be so small as to be impossible to measure – something like 10-3,678 of the original.

Even with younger samples, things can go wrong. Homo floresiensis, the so-called “Hobbits” of Flores Island, made headlines in 2004 when it was discovered that populations of the hominin had been around as recently as 12,000 years ago – but it turned out to be a mistake. The team who had originally carried out the research had dated the H. floresiensis remains by analyzing the sediment in which their bones were discovered, rather than the bones themselves. That’s normally a perfectly acceptable technique – except that the team didn’t realize the remains lay within an unconformity, making them appear younger than they really were.

Mix-ups in the timeline

In fact, the Hobbits had lived more than 60,000 years ago – not as exciting, but it made much more sense chronologically. There was no longer the puzzle of how H. floresiensis could have survived alongside H. sapiens – that is, us – for so long without being bred or fought or hunted into extinction. The two species, it transpired, did not actually overlap in the area by very much at all.

And a strikingly similar mix-up has been revealed by the new analyses. Back in 2010, researchers in the Philippines discovered the remains of what would later be recognized as a new archaic human species, Homo luzonensis. As with H. floresiensis, what was shocking about the find was just how new it appeared to be: initial estimates put the age of the fossils at roughly 65,000 years old, within the period when the area was inhabited by Homo sapiens.

But again, this has turned out to be false – and the remains are in fact at least twice as old as previously thought.

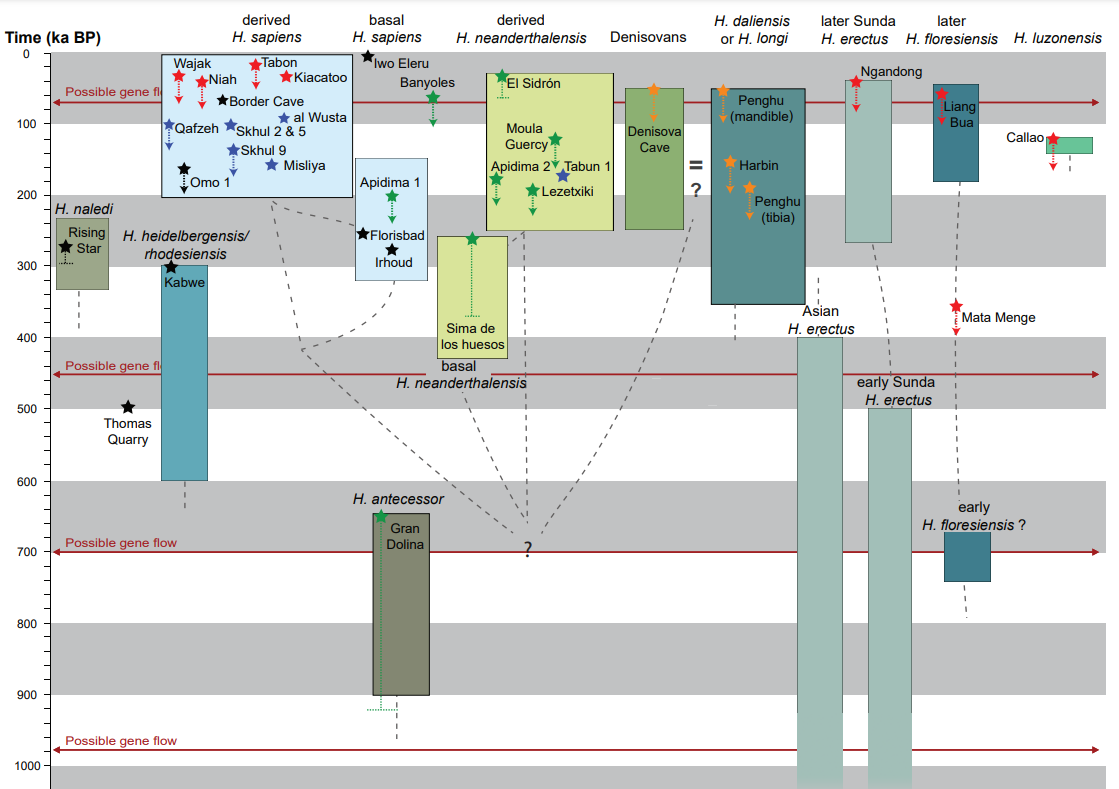

The changes in the timeline as a result of the new dating techniques.

Image credit: NHM

An improved method

How do the researchers know? The reanalysis was done using radiometry, but not by measuring carbon-14 levels – instead, the team used a technique known as U-series, or uranium-thorium dating. It’s a method that’s been in use for half a century already, so you might wonder why the results weren’t right before – but the key is in the novel ways Grün and his colleagues have developed the tech, allowing for pin-pointed accuracy that was once impossible.

“The problem with bone is that it’s an open system,” said Chris Stringer, Research Leader at the Natural History Museum, in a statement. “Uranium can get into the bone, allowing it to be dated, but more can also be added or washed out over time.”

“Previously, you might need to cut a fossil in half and track the uranium all the way through the bone, but this wasn’t feasible on valuable fossils such as the ones we were reanalyzing,” he explained. “Instead, Rainer [Grün, Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University in Canberra] has helped to miniaturize the process, so that tiny samples can be taken using lasers to minimize damage to important areas of the specimen.”

Fixing history

And the new analysis has turned up some pretty groundbreaking results. Take, for example, the two skull fragments, one from a Homo sapiens and the other from a Neanderthal, found in the Apidima Cave in Greece in 1978. Originally, radiometric dating threw up some surprising figures, with the Neanderthal skull registering as 40,000 years younger than the Homo sapiens – which seemed unlikely, given what we know about the two species’ relative positions in time.

Instead, scientists argued, it was perhaps two Neanderthal skulls – one of which was a bit weird, sure, but definitely not a Homo sapiens. And as for the dates – well, that couldn’t be right either: not only did Neanderthals come before modern humans, but the figures radiometry was churning out – something like 210,000 years for the supposed Homo sapiens – were simply far too early for H. sapiens to be hanging out in Europe.

But now, with the researchers’ updated methods, that mix-up has been unmixed down – and in a perhaps unexpected way. It turns out the two fossils were originally deposited in two different places, and both fell into the cave over time. That’s why they were found together despite the 40,000-year age gap – and why the H. sapiens skull fragment, dating from more than 150,000 years earlier than anatomically modern humans were previously thought to have migrated into Europe, is now being celebrated as the oldest fossil of the species ever found in Europe.

“Some of these findings are astonishing,” noted Grün, “but [they] provide an excellent outlook for increasing our understanding of human evolution.”

The paper is published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

Source Link: A New Look At Some Old Fossils Has Just Rewritten The Story Of Human Evolution