A game of pin the ear on the reptile would likely highlight a gap in the average person’s knowledge surrounding turtle ears, but new research has taken a good look inside their noggins and found they’re surprisingly big. The apparatus in question is known as a bony labyrinth and as researchers on a new study recently found out, it’s comparatively larger than that of most mammals and more comparable to those of birds.

The vertebrate labyrinth gets its Bowie-esque name due to the role it plays in balance. It contains membranes that are able to detect changes in head rotation and acceleration, without which we’d be wobbling all over the place (one of the key symptoms of labyrinthitis, a type of inner ear infection that affects this structure, is dizziness and vertigo).

Historic research into the labyrinth has concluded that its shape and size is predicted by an animal’s environment and agility, but little research into this had been done outside of mammals. To challenge this, researchers on the new study looked at the labyrinths of modern and ancient turtles to see how the structure has changed across evolutionary history.

They investigated 163 specimens, 90 of which were extant species like softshell turtles, terrapins, and loggerhead sea turtles, and 53 of which were extinct. In life, the specimens studied would’ve represented a diverse range of lifestyles with talents such as burrowing, terrestrial locomotion, underwater locomotion, and swimming up their flippers.

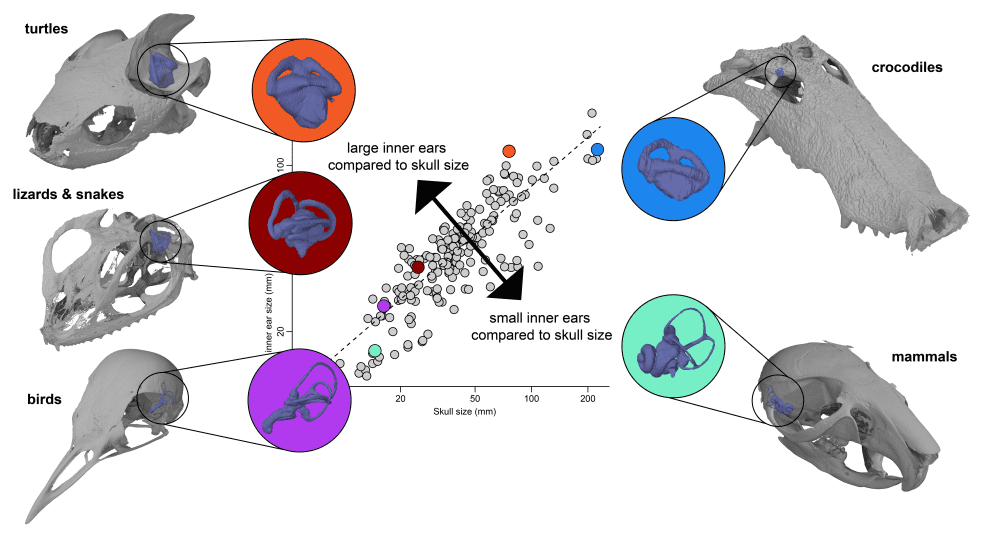

Relative inner ear sizes of major vertebrate groups compared. Turtles, birds and lizards show large inner ear sizes compared to their heads, whereas mammals and crocodiles have small inner ears. Image credit: Serjoscha Evers

The analyses revealed that turtles have surprisingly large inner ears considering their modest head size, possibly indicating that big inner ears are an adaptation to an aquatic lifestyle and perhaps improve visual acuity. They also revealed that the bony labyrinths of turtles are larger than that of other vertebrates including mammals, being most similar in relative size to those of birds.

“We show that turtles have unexpectedly large labyrinths that evolved during the origin of aquatic habits,” concluded the authors. While historically, the labyrinth has been thought to be positively correlated in size with agility (an assumption built largely on mammalian research), few would put the leisurely flipper strokes of turtles in this category, demonstrating that what influences its size is something else entirely.

“We also find that labyrinth shape variation does not correlate with ecology in turtles, undermining the widespread expectation that reptilian labyrinth shapes convey behavioral signal, and demonstrating the importance of understudied groups, like turtles.”

This study was published in Nature Communications.

Source Link: A Peek Inside Turtle Ears Has Turned Up Fresh Insights Into Vertebrate Evolution