The planet 55 Cancri e has puzzled astronomers who have observed evidence of an atmosphere during some secondary eclipses, but not others. Geochemical outgassing from its magma ocean may provide the answer.

Most of the planets we have found would be pretty unpleasant places for humans, but few are quite as bad as the super-Earth 55 Cancri e, whose temperature makes even Venus look tame. Observations made when it passes behind the star 55 Cancri A, known as secondary eclipses, produce inconsistent signals, which astronomers are keen to explain.

If you’re one of those people who sees the word “signal” in reference to astronomy and thinks aliens you’re going to be disappointed (actually, that will happen a lot). No one imagines a world this hot could support life, let alone a technological civilization. To astronomers, signals can refer to anything that isn’t noise, in this case referring to signs of specific gases that may represent an atmosphere.

The confusing part in this case is that 55 Cancri e orbits its star every 18 hours, giving us plenty of chances to look for gases, and they only show up some of the time. Some teams have reported signs of hydrogen cyanide and nitrogen, while others have said there is no hydrogen, and probably no gas at all. Stranger still, the results when the planet passes in front of the star are much more constant.

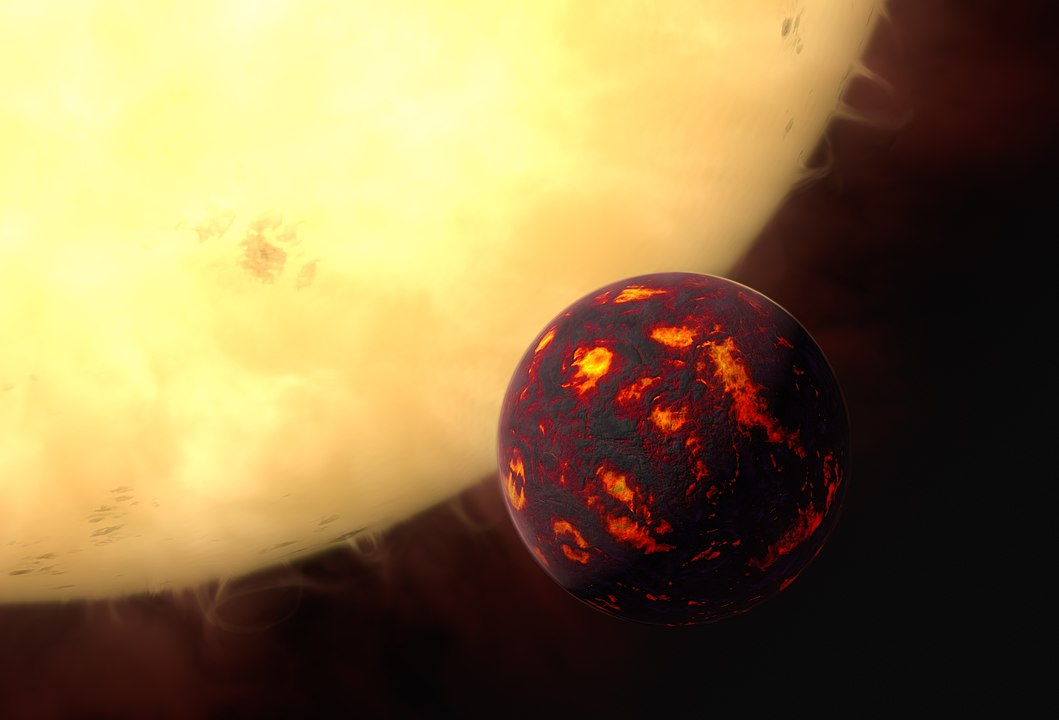

Artist’s impression of a planet so hot even its permanent night side is molten, and its parental star.

Image credit: ESA/Hubble

In a paper recently accepted for publication, Dr Kevin Heng of Ludwig Maximilian University argues it’s not that some teams are wrong, but that they are observing at different times.

Heng proposes there are chambers of gas beneath 55 Cancri e’s surface, and that these sometimes vent, creating a thin temporary atmosphere. At such high temperatures the gases move fast. Helped by exposure to a stellar wind straight off the star, molecules can escape the planet’s gravity within a single orbit, explaining the varied observations.

This theory is testable, Heng argues, but only if we observe 55 Cancri e at optical wavelengths at the same time as the JWST captures it in infrared light. If he’s right, both should either detect an atmosphere, or what Heng calls its “bare rock” phase.

55 Cancri e has a mass around eight times that of the Earth; when found in 2004 it was the first so-called super-Earth (a rocky planet substantially more massive than our own world) to be discovered. It is almost certainly tidally locked, in which case the starward side would be molten with temperatures in the thousands of degrees. Unlike many such worlds, however, even the side that never sees its star is thought to be staggeringly hot, probably more than 1,100°C (2,000°F).

Astronomers study the atmospheres of planets when they pass between us and their star by looking at the way light is affected as it travels to us. Their use of secondary eclipses is less intuitive. Normally, however, we are seeing a combination of light from both planet and star, but it can be hard to distinguish the two. If we subtract the light collected from when the planet is hidden from what we pick up when both are visible, however, we can measure the difference, and see if it indicates the presence of specific gases.

There’s nothing particularly extraordinary about 55 Cancri A, it’s a K-type a little cooler than the Sun. It’s the extraordinary closeness of its planet that makes the situation extraordinary.

The study will be published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and a preprint is available on ArXiv.org.

Source Link: A Possible Explanation For Strange Signals From “Hell Planet” 55 Cancri e