For at least 45 years, an object in our galaxy has been emitting radio waves every 21 minutes, and astronomers are very confused about what could be causing it. The cycle is too slow and too powerful to be anything we are familiar with, but too broad to be the product of a technological civilization. Its discoverer has a lot of ideas on how to investigate, but not yet the funding to do most of them.

Last year Dr Natasha Hurley-Walker of Curtin University and her PhD student Tyrone O’Doherty announced the discovery of something unprecedented in data from 2018. The Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) had picked up radio pulses emitted every 18 minutes on and off for three months by an object that got labelled (GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3. By the time Hurley-Walker and O’Doherty went back to look, nothing seemed to be going on at the source.

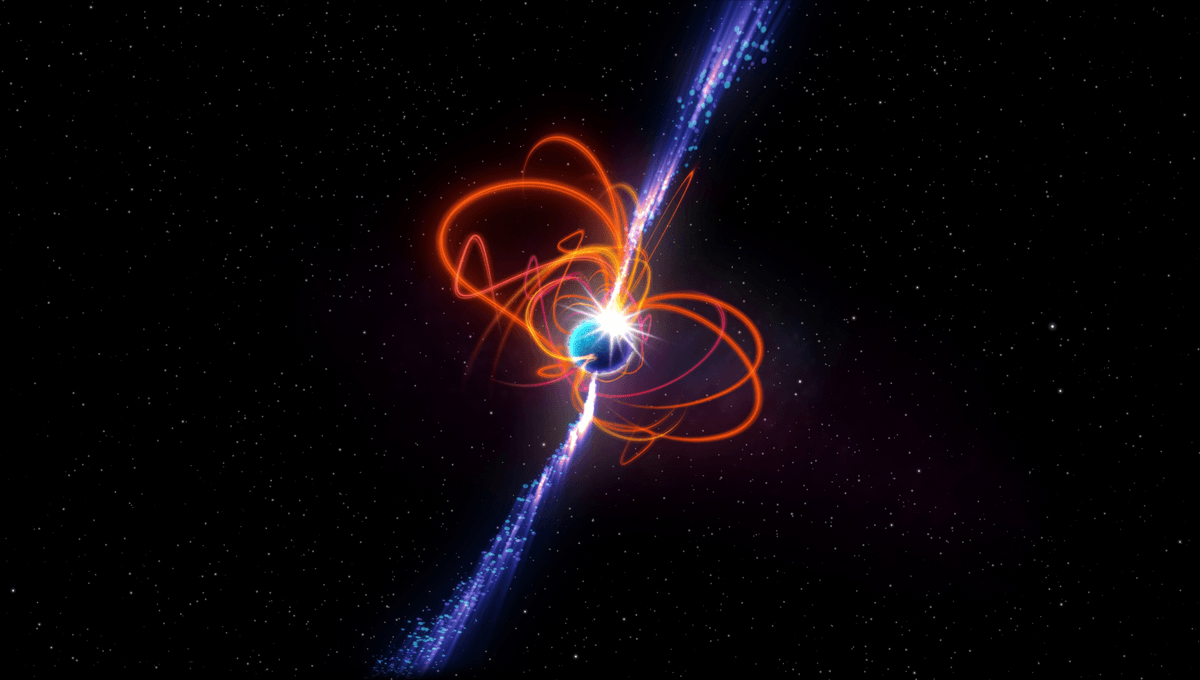

(GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3 didn’t fit with anything we knew. If it had been faster, it would have been labelled a magnetar, a type of neutron star whose astonishingly powerful magnetic field causes regular radio pulses. However, the slowest magnetar cycle is 76 seconds, whereas this was 1,318 seconds. Moreover, magnetars get weaker as they get slower and astronomers consider anything with a cycle significantly longer than 100 seconds to be undetectably faint.

At the time Hurley-Walker proposed a few possible explanations to IFLScience, although she admitted nothing really fit. The best way to answer the question, she thought, was to find another such object, so she searched MWA data around the galactic plane for something similar.

Now Hurley-Walker has announced she hit the jackpot, not only finding an object with similar behavior, but observing it while it is still emitting. Other instruments have checked it out, adding information like its polarization. Unfortunately for those who like neat answers, the new discovery, GCRT J1745–3009, rules out even the tentative explanations for (GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3. This object couldn’t be much more mysterious if it tried.

“This remarkable object challenges our understanding of neutron stars and magnetars, which are some of the most exotic and extreme objects in the Universe,” Hurley-Walker said in a statement. Indeed there’s a high chance it’s not a neutron star at all, but if so we don’t know what it is.

GCRT J1745–3009 has a slightly longer cycle than (GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3, 21 minutes, during which it emits for 30-300 seconds before going silent. However, it’s not the timing that bothers Hurley-Walker the most. (GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3 was only detected 71 times, opening up the possibility it was drawing on some temporary source of energy. However, examining old records from other instruments found detections of GCRT J1745–3009 in 1988, 2001-2 and 2007. Throughout that time its cycle has been unchanged.

This consistency also squelches another explanation offered for (GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3. Last year Hurley-Walker told IFLScience she couldn’t rule out the possibility two objects were on mutual elliptical orbits, producing bursts of energy every 18 minutes as they approached each other, although she had failed to make a model that worked.

Now she says decades of observations mean, “We can time GCRT J1745–3009 incredibly precisely. It switches on and off so consistently. There’s no physics you can torture to create a model [of companion objects] that creates that.” Moreover, in the 18 months since publishing her paper on (GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3 no one else has constructed a satisfactory model for it either, making her more confident the original also can’t be explained that way.

As with (GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3, there’s no point invoking aliens for GPM J1839–10. The signal is simply too broad-spectrum and powerful to be a product of a technological civilization. “Saying ‘it’s aliens’ doesn’t solve the problem,” Hurley-Walker told IFLScience. “It makes it much, much worse.”

Efforts to identify GPM J1839–10’s source in visible light have failed; Hurley-Walker told IFLScience the field is simply too crowded with stars to work out which one is responsible, if we can see it at all. “We need the James Webb, which is quite hard to get time on,” she noted at a press conference.

The paper tentatively offers the possibility GPM J1839–10 might be a highly magnetized white dwarf, but while that solves a few problems it raises plenty more. No magnetized white dwarf stars have been seen producing anything like this, and the closest comparison is a thousand times fainter.

Hurley-Walker told IFLScience the most likely way to solve the mystery is to find similar objects, preferably in less crowded parts of the sky. To do that she wants to search old data from a variety of radio telescopes, but despite having written the algorithms to do it, will still need more time than she can personally afford to sort the results. “All I want is one postdoc,” she told IFLScience, but alas so far no one has agreed to pay the salary.

One thing that is not mysterious is how no one noticed GPM J1839–10 before, despite multiple observations. “In science we are usually performing a specific search,” Hurley-Walker told IFLScience. “We have a plan on how to observe and how we are going to process the data, not randomly and speculatively process it in the hope something will pop out.” Since no one expected something like GPM J1839–10 until (GLEAM-X) J162759.5-523504.3 was found searches were tailored to look for much shorter signals.

Hurley-Walker has now comprehensively searched the galactic plane for anything with a duration between four and 250 seconds, with downtimes of minutes or hours. She acknowledges however, that this would not find something like GCRT J1745–3009, also known as the “galactic center burper”, which released five radio bursts each 11 minutes long in 2002 and, after two weak follow-ups, was never heard from again. There are stranger things in the galaxy than we know.

The study is published in Nature.

Source Link: A Repeating Radio Burst Astronomers Can’t Explain Isn’t Going Away