In November 2005, Alex Simpson was born in Omaha, Nebraska. Her diagnosis wasn’t good.

At first, everything seemed fine – until she was 2 months old. Then, the problems began: Alex was crying 20-22 hours a day; she was having trouble digesting milk – and when her parents took her to the hospital, the reason became clear.

Alex had no brain.

Or, to be more accurate, she had no cerebrum. She was born with a disease called hydranencephaly, where the biggest, wrinkly, most “brain” bit of the brain never develops. Her doctors told her parents that she would likely not live past 6 months old – and, indeed, that’s usually what happens for babies with the condition.

Instead, Simpson and her family celebrated her 20th birthday this year. But what is this rare disease she’s lived with?

What is hydranencephaly?

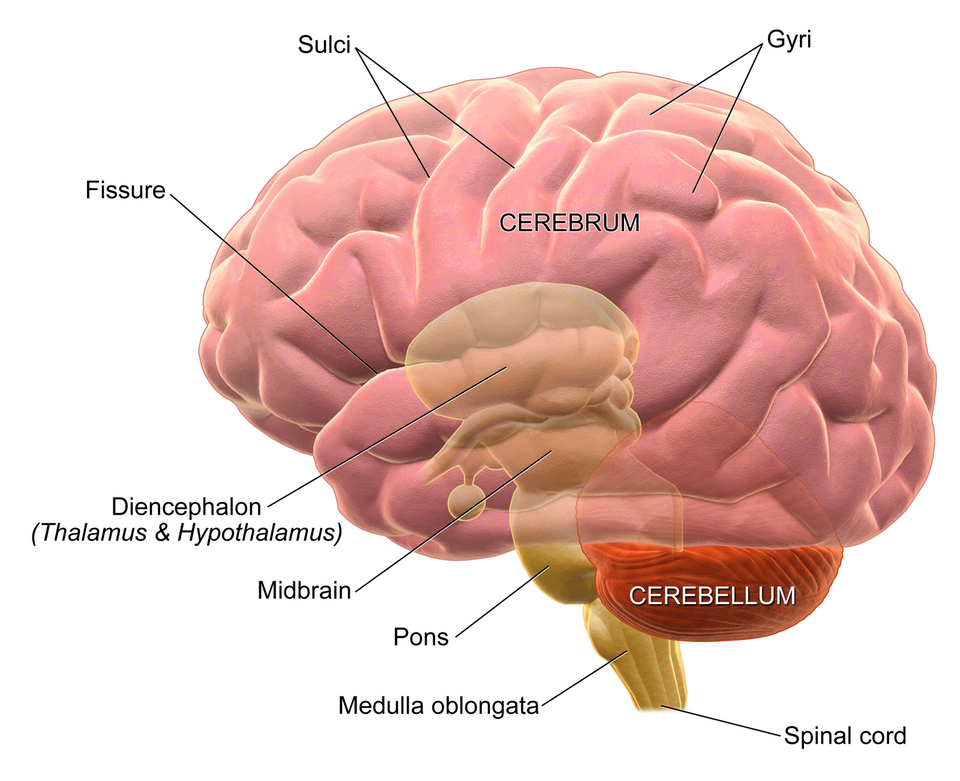

When you visualize a brain, most of what you’re imagining is in fact just one part of it: the cerebrum. It’s admittedly a very important part – it’s what gives us thoughts and consciousness, among other things – but it’s not the whole thing.

It’s hard to appreciate in humans, because our cerebra are just so overgrown and bulbous compared to everything else, but there’s actually two other pieces of brain nestled underneath there. Right at the back, underneath the cerebrum, there’s the cerebellum – Latin for “little brain”, this is the bit that regulates and fine-tunes movement and motor skills – and even deeper than that, the tiny brainstem, where the body’s most basic functions are taken care of.

The three parts of the brain.

Usually, these three sections of the brain develop in utero with both staggering speed and remarkable predictability. By four weeks’ gestation, the neural plate – the precursor to the nervous system – has already developed; within two or three weeks from that, there’s already a rudimentary brain, with distinct fore, mid, and hind sections.

It’s after this that things start to go wrong for fetuses with hydranencephaly. Normally, starting in the seventh week, those three basic divisions start to specialize further: the hindbrain births the metencephalon and myelencephalon, and the forebrain becomes the diencephalon and the cerebrum.

But sometimes – very rarely – that doesn’t happen. For whatever reason, instead, the cerebrum fails to develop; babies with hydranencephaly are born with only the cerebellum and brainstem, with the rest of the cranium filled by sacs of cerebrospinal fluid.

Diagnosis and prognosis

Hydranencephaly is very rare – it only occurs in around one in every 50,000 live births. Partly, that’s just its nature – scientists estimate it only occurs in about one in 10,000 pregnancies at all; partly, though, it’s because the majority of fetuses with the disorder never survive the pregnancy.

For those of us with the benefit of modern medicine, the discovery of hydranencephaly in a fetus often happens early. Diagnoses can be made using an ultrasound scan, which most expectant mothers would receive as routine care: “Performed during the 21 to 23 weeks of gestation,” notes one 2023 writeup of the condition, this technique would reveal the “absence of cerebral hemispheres, replaced with homogeneous echoic material” and the preservation of other brain areas.

“Although most commonly used during pregnancy, this test can be also used during the postnatal period to obtain a diagnosis,” the authors add.

But of course, this isn’t foolproof. Fetuses with hydranencephaly often exhibit normal movements from the mother’s perspective, and that pattern can continue after the birth: babies with the condition might appear typical at first, and diagnosis isn’t made until weeks or even months later, once symptoms become obvious.

Other times, it’s evident right from the start. The baby will be born with an enlarged head; soon, they can start to seize and spasm, crying far more than typical babies and feeding poorly. They fail to thrive, and rarely live past the first year.

Precisely how long any patient can live depends on how much of their brain is present and working – “The more developed your baby’s brain is, the greater chance they might have to live past infancy,” as WebMD neatly summarizes. In one case, a woman born with the condition lived to 33 years old, but she never learned to walk and was fully dependent on caregivers; another woman reached at least the age of 32, and could walk, but never learned to talk or use the toilet.

The median age of survival with hydranencephaly is under 8 years old.

How has Alex Simpson survived so long?

As one of the few people to have lived with hydranencephaly for more than two decades, then, it’s clear that Alex Simpson is a notable individual.

Her diagnosis, made two months after she was born, “means that her brain is not there, not half a brain, her whole brain,” Alex’s father, Shawn Simpson, told Omaha’s KETV earlier this month.

“Technically, she has about half the size of my pinky finger of her cerebellum in the back part of her brain, but that’s all that’s there,” he said.

Simpson’s life is one that requires round-the-clock care: she has a feeding tube in her stomach and a tracheostomy tube in her throat; she can’t control her jaw or tongue, and so risks choking if she lays down at the wrong angle; she requires valium to fall asleep at night. She has, at most, impaired hearing and vision, even if her cerebellum does allow her some awareness of her surroundings.

“She knows her mum and her dad, her little brother,” Shawn Simpson told KETV back in 2016. “She knows when good things are going on around us, she knows when bad things are going on around her.”

Why does hydranencephaly occur?

For Alex, as for all babies with hydranencephaly, this kind of intense care is the only treatment they will see. There’s no cure for hydranencephaly; no way to regrow or develop a patient’s missing brain tissue.

For the parents involved, one question must surely add to the already overwhelming stress: did I cause this? And the answer, most likely, is “no”.

“While we are still learning, hydranencephaly is presumed to be a destructive process impacting the brain,” Sumit Parikh, a pediatric neurologist with the Cleveland Clinic, told MedPage Today – and it’s “commonly due to a variety of causes.”

But exactly what those causes are, we don’t really know. It could be due to a freak infection in utero; it could be due to an environmental toxin like cocaine. Sometimes, it can occur due to twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, an extremely rare situation in itself.

In Simpson’s case, her doctors believe it was caused by a stroke in the womb. This, they think, cut off the oxygen supply to her developing brain – and, indeed, hydranencephaly is believed to usually be traced back to an interruption to the brain’s oxygen supply like this. That’s often due to a blocking of the carotid arteries; sometimes, the blood vessels simply can’t deliver enough oxygen for some reason.

“Less commonly, genetic disorders impacting cerebral blood vessel formation have been identified,” said Parikh. “Considering we have not had comprehensive testing like whole-genome sequencing until relatively recently, it is possible that genetic causes have been underestimated.”

Whatever the cause, though, there’s little that parents can do to change their child’s chances of having hydranencephaly. Nevertheless, when it happens, it’s “extremely difficult,” notes the Cleveland Clinic. “Families need education to understand how severe the disorder is.”

Source Link: A Woman Born Missing Most Of Her Brain Just Celebrated Her 20th Birthday. What Does That Mean?