After the first humans set foot on the Moon and successfully splashed back onto Earth, their mission wasn’t quite over. While it may seem a strange idea now given what we know about the lifelessness of the lunar surface, at the time there were a lot of unknowns. Upon their return, the crew of Apollo 11 spent 21 days in quarantine just in case they had returned from our satellite carrying dangerous microorganisms.

In the 1960s, a new field of “exobiology” was emerging, studying the potential for microbial life outside of our planet, though it was largely ridiculed as a discipline.

“In response, exobiologists argued that only their field could mitigate the gravest risks and exploit the greatest opportunities of the new Space Age,” historian Dagomar Degroot of Georgetown University wrote in a new paper. “They stressed that microbial life could be ubiquitous across the solar system. Missions to other worlds therefore had to guard against both forward contamination, which could jeopardize the detection of extraterrestrial life, and back contamination, which could threaten life – including human life – on Earth.”

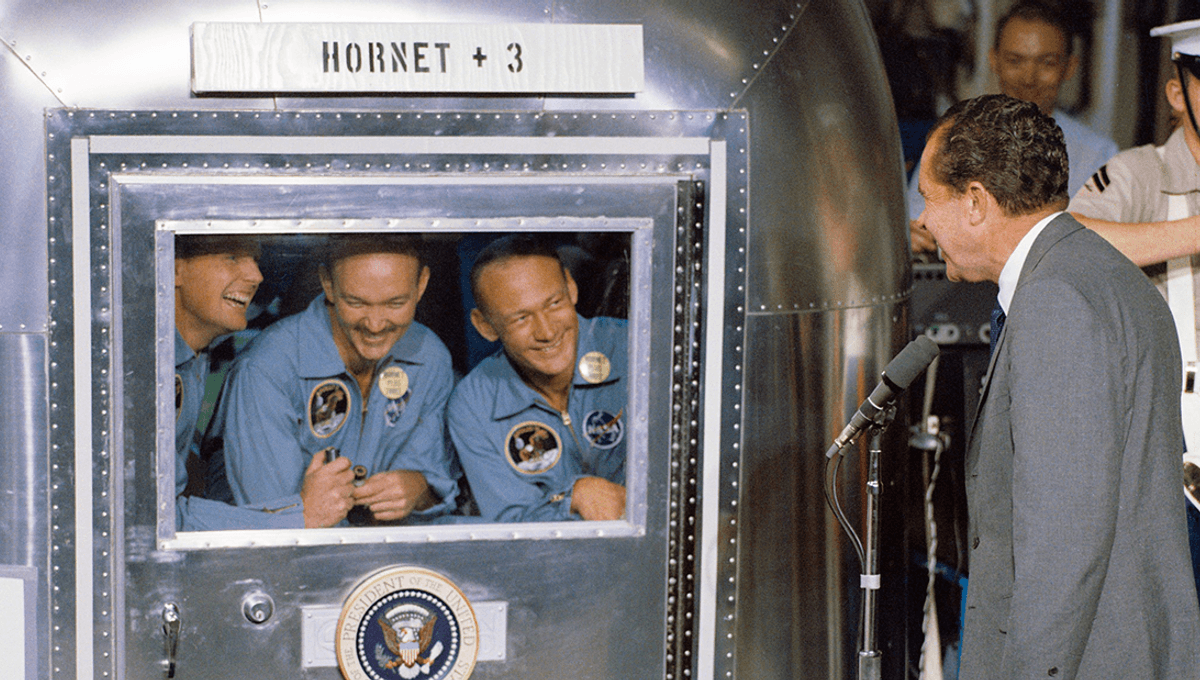

Though most thought the surface of the Moon to be lifeless, there were those – including Carl Sagan – who thought it possible microbial life could still be alive just below the surface. NASA, partly to reassure the public, designed a Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL) where Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins would stay, along with any potentially hazardous microorganisms from the Moon that could devastate life on Earth. Sagan, for his part, compared the possibility of microbial life making its way back to Earth to “the violence of the venereal disease epidemics that raged through Europe in the Middle Ages, or to the measles that took a heavy death toll when it was introduced into Polynesia.”

We all know what happened after that. All three astronauts were fine, and no alien life was released onto the planet that could endanger humanity. But, according to the new paper, had lunar microorganisms actually existed, the procedures to prevent them from returning to Earth would have likely have failed.

“In all probability, the microorganisms that seemed most likely to evolve on the Moon would have infected the astronauts, contaminated their spacecraft, escaped into the Pacific Ocean, and breached containment in the LRL, just as tests on plants – and bacteria apparently returned from the Moon – made headlines across the United States,” Degroot writes in the paper. “The quarantine protocol looked like a success only because it was not needed.”

There were many problems with the procedure, outlined by Degroot. The capsule used to land the Apollo 11 crew in the Pacific Ocean vented itself as it came down, potentially releasing any microbes into the atmosphere. Then when it touched down in the ocean, it was opened in order for them – and any deadly microbes – to escape into the ocean.

“If lunar organisms capable of reproducing in the Earth’s ocean had been present, we would have been toast,” former NASA planetary protection officer John Rummel told the New York Times.

The astronauts too could have been in danger as they returned from the Moon to their craft.

“Moon dust was everywhere. Because it irritated the skin and lungs, both astronauts slept in their helmets and gloves that night. Removing all the dust was clearly impossible,” Degroot wrote. “If it had harbored a pathogen, it would easily have infected the astronauts.”

When astronauts returned to Earth, the film they used to take photographs of the Moon was quickly processed for the public. While the films were sent to be decontaminated using ethylene oxide gas, five technicians found that they had been exposed to moon dust while handling it.

NASA, who knew that contamination from alien lifeforms was highly unlikely, also likely knew that there were many failures in their quarantine procedure. By the time it was over, 24 people had been quarantined for potential contamination. Degroot writes that NASA, motivated by beating the Soviets to the Moon, did not take the time to create adequate protections for astronauts, nor Earth.

“For almost a year, tests and simulations had uncovered critical problems with the autoclaves, and federal officials had repeatedly warned that they urgently needed fixing,” Degroot wrote. “Yet there had not been enough time to prepare them for the arrival of the Apollo 11 astronauts, the command module, film magazines, and samples. Had Apollo 11 returned microorganisms from the Moon, they would likely have escaped.”

NASA has of course worked on new guidelines for quarantining samples from outside of Earth since the Apollo program. Hopefully soon, we will be able to test them with samples from places much more likely to harbor life.

The study is published in the journal Isis.

Source Link: After Returning From The Moon, The Apollo 11 Crew Quarantined. Then It All Went Wrong