The organizers of the Vesuvius Challenge, which started in 2023, have now announced their grand prize winners who have successfully revealed ancient secrets hidden on petrified scrolls. The announcement not only marks the outcome of ingenious work but may also indicate an exciting new era of research.

The Vesuvius Challenge was launched in March 2023 with the not-too-ambitious aim of “making history” (which, it is safe to say, they have probably achieved). The organizers encouraged individuals from diverse academic backgrounds to devise new methods to read ancient scrolls recovered from the pyric remains of Herculaneum, Italy.

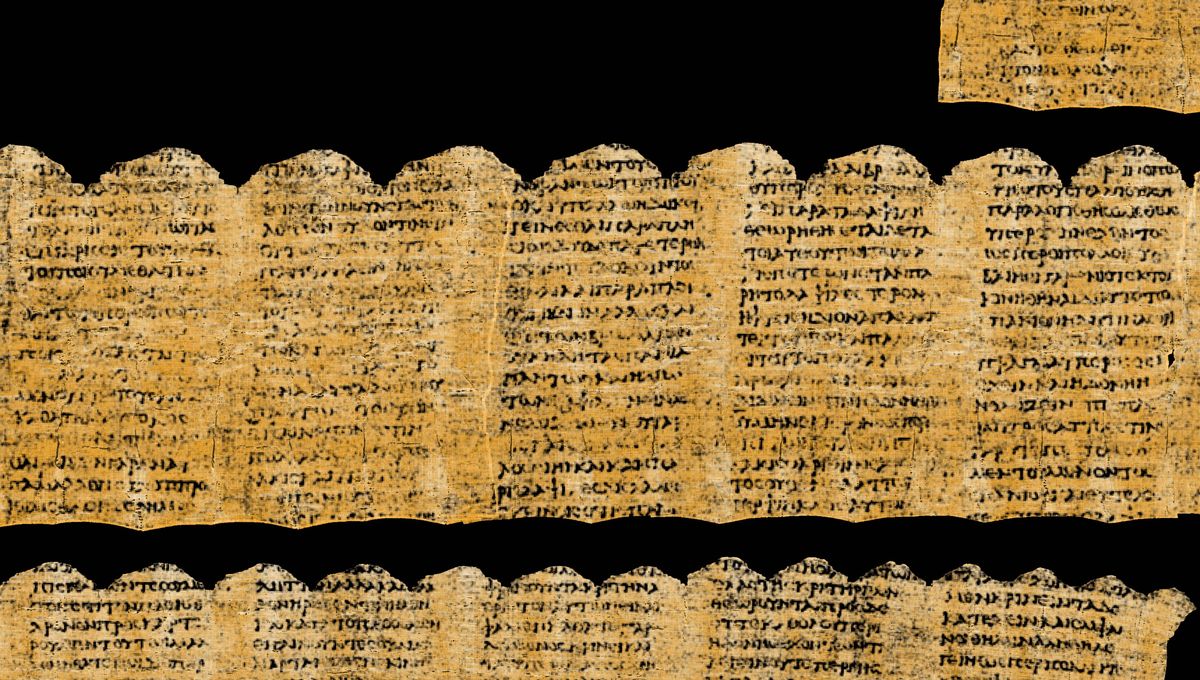

The scrolls, which are now completely petrified, were originally located in the Villa Papyri, a wealthy estate that was buried under volcanic ash and debris when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE.

The estate, and its library, were then rediscovered in the 1700s, but despite being well preserved, the scrolls have remained unreadable. This is because the heat from the eruption essentially “flash-fried” them, turning them into carbonized lumps. But now, after 10 months of hard work, the winners of the Vesuvius Challenge have found ways to unravel these invaluable artifacts using artificial intelligence (AI) techniques that scan their content without damaging their fragile structure.

Nat Friedman, the former GitHub CEO, and a team of scientists launched the Vesuvius Challenge to find new ways to approach these once-obscure texts. They launched the competition with various financial prizes, including the $700,000 Grand Prize, to anyone who could help unlock them.

Then, back in October 2023, Friedman announced the First Letters prize to a 21-year-old computer science student, Luke Farritor, who managed to decipher the word “πορφυρας” on a scroll, which means “purple dye” or “cloths of purple”. This prize was soon followed by another for Youssef Nader, who identified the same work but with more clarity.

Both these results would not have been possible without the work of Casey Handmer, the winner of the First Ink prize, who found a way to identify the presence of ink in the unopened scroll.

Now, Friedman has announced the winners of the Grand Prize for their ground-breaking effort to reveal over 2,000 Greek letters from the scroll.

“We received many excellent submissions for the Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize, several in the final minutes before the midnight deadline on January 1st”, Friedman and colleagues wrote on their competition’s website.

“We presented these submissions to the review team, and they were met with widespread amazement. We spent the month of January carefully reviewing all submissions. Our team of eminent papyrologists worked day and night to review 15 columns of text in anonymized submissions, while the technical team audited and reproduced the submitted code and methods.”

But from all the incredible submissions, there was one that stood out from the rest. The submission was so rich that, while working independently, each member of the team of papyrologists was able to recover more text from it than from any other.

As the Vesuvius Challenge organizers explained: “Remarkably, the entry achieved the criteria we set when announcing the Vesuvius Challenge in March: 4 passages of 140 characters each, with at least 85 [percent] of characters recoverable. This was not a given: most of us on the organizing team assigned a less than 30 [percent] probability of success when we announced these criteria! And in addition, the submission includes another 11 (!) columns of text — more than 2,000 characters total.”

The team responsible for this massive success consisted of Farritor and Nader, the winners of the earlier prizes, and Julian Schilliger, the winner of three Segmentation Tooling prizes for his work on Volume Cartographer. Schilliger’s work had allowed for the 3D mapping of the papyrus areas used in the winning submission.

“For the Grand Prize, [these three previous winners] assembled into a superteam, crushing it by creating what was unanimously deemed the most readable submission.”

For more details on how the team achieved this, see the Vesuvius Challenge’s breakdown of their process and how each member contributed to and built on the work of the other.

So what does it say?

So far, the researchers examining the first scroll have managed to read about 5 percent of it. The preliminary transcription indicates that this is a completely original text and not a duplicate of other work. It seems this philosophical text addresses the subject of “pleasure”, the highest form of good according to Epicurean philosophy.

“In these two snippets from two consecutive columns of the scroll, the author is concerned with whether and how the availability of goods, such as food, can affect the pleasure which they provide.” The papyrologists explain.

“Do things that are available in lesser quantities afford more pleasure than those available in abundance? Our author thinks not: ‘as too in the case of food, we do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant.’ However, is it easier for us naturally to do without things that are plentiful? ‘Such questions will be considered frequently.’”

It seems this question was posed at the end of the text, which suggests the answers may be held in other scrolls in the same collection. Interestingly, the beginning of the first test text mentions a Xenophantos, who may have been a musician and was also mentioned in the work On Music by Philodemus, an Epicurean who may have been the philosopher-in-residence at the Villa Papyri.

“Scholars might call it a philosophical treatise”, the organizers of the Vesuvius Challenge explain. “But it seems familiar to us, and we can’t escape the feeling that the first text we’ve uncovered is a 2,000-year-old blog post about how to enjoy life. Is Philodemus throwing shade at the stoics in his closing paragraph, asserting that stoicism is an incomplete philosophy because it has ‘nothing to say about pleasure?’ The questions he seems to discuss – life’s pleasures and what makes life worth living – are still on our minds today.”

What is clear is that this is just the start of what may be a whole new chapter in historical analysis. A new and exciting rediscovery of ancient works that, apparently, not even a volcano could conceal forever.

Source Link: AI Helps Decipher Herculaneum Scroll That Hasn't Been Read In 2,000 Years