When the Manhattan Project set out to research and develop nuclear weapons during World War II, it became apparent to the scientists involved that they would need to better understand the effects of the radioactive materials they were going to be working with on the human body. To find out, they conducted Human Plutonium Injection Experiments.

Albert Stephens was one “participant” of many enrolled in the experiments, and he was assigned the codename “Patient CAL-1” as the first California patient to be injected with plutonium. We say “participant”, because there’s no evidence to suggest Stevens was ever made aware of what he was being injected with, nor asked for his consent to be exposed to plutonium.

The Human Plutonium Injection Experiments

The Human Plutonium Injection Experiments aimed to establish what happened to the human body when exposed to radioactive isotopes of the element. It would be a key ingredient in the atomic bomb known as “Fat Man”, which was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 6, 1945, by the US Army.

The Manhattan Project established a Health Division in 1942, first experimenting on rats, and later – when animal tests were declared insufficient to inform worker guidelines – moving on to human subjects. According to a report from Los Alamos Laboratory published in 1962, the experiment selected terminal patients who were assumed to have a life expectancy of less than 10 years.

Plutonium-238

Stevens would become the first patient to get a plutonium-238 injection in California, reports the Nuclear Museum, unknowingly receiving a dose that was considered to be “many times the so-called lethal textbook dose”, writes Jacques G Richardson in Serious Misapplications of Military Research. As a radioactive isotope, plutonium-238 is significant because it’s 276 times more radioactive than plutonium-239, which was also included in Stevens’ injection cocktail.

According to Eileen Welsome, author of The Plutonium Files, it was probably used because it was easier to measure with the equipment the Manhattan Project researchers had available to them at the time. Unfortunately, it also had much more potential to cause biological damage.

“In 1995 two Los Alamos scientists calculated that Albert received a dose equal to 6,400 rem during his lifetime,” she wrote. “That translates to 309 rem per year, or 858 times what the average person receives during the same period.”

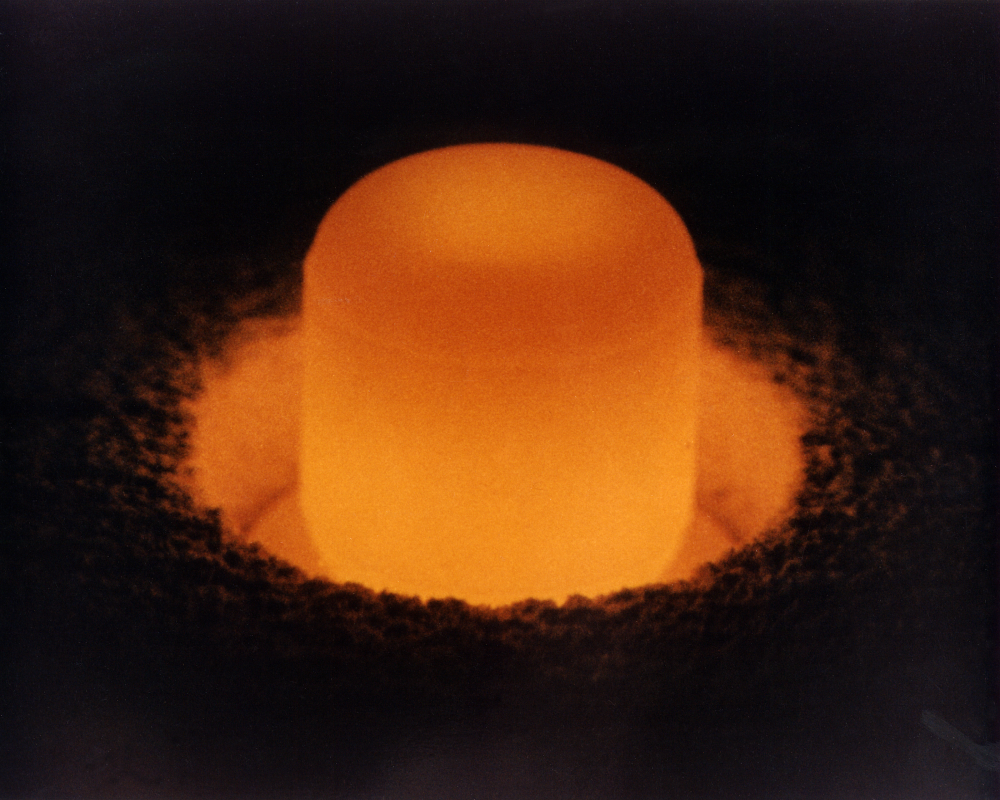

Plutonium-238 pellet under its own light

“Terminal” Candidates

Stephen’s case is particularly unusual because, during an operation following the plutonium injection, it was revealed that the painter-by-trade wasn’t terminally ill at all. What was thought to have been a cancerous stomach ulcer was revealed to be a benign gastric ulcer with chronic inflammation.

Despite the high dose of radiation, being injected with plutonium had no immediate, acute effect on Stephens, and he died of cardiorespiratory failure 21 years following the exposure on January 9, 1966. Welsome writes that in an interview with medical historian Sally Hughes, a scientist named Kenneth Scott – who prepared Stephen’s injection but claimed Earl Miller administered it – revealed that they never told him about the plutonium or that he was involved in any kind of experiment, but used his financial problems as an opportunity to gather data by offering to pay him for stool and urine samples.

During the radical surgery to remove Stephens’ “cancer”, samples of several body parts were taken but never made it to the pathology lab, as the scientists had claimed they would. According to Welsome’s investigations, the reason why may have surfaced in 1946.

“A Comparison of the Metabolism of Plutonium in Man and the Rat”

“Almost a year after Albert’s injection, the Berkeley group published a classified report titled ‘A Comparison of the Metabolism of Plutonium in Man and the Rat.’ The abstract begins: ‘The fate of plutonium injected intravenously into a human subject and into rats was followed in parallel studies’,” Welsome wrote.

On the day of Steven’s injection, five rats were also injected with the same plutonium cocktail.

A description of the body parts removed from Albert on the operating table – the specimens that were not delivered to the pathology department – appears in the report. “Four days after the plutonium had been administered, specimens of rib, blood, spleen, tumor, omentum, and subcutaneous tissue were obtained from the patient.”

That Stephens didn’t have cancer was also never shared with Stephens or his family, and it was never explained why he continued to be monitored in the decades that followed the plutonium injection. According to the Department of Energy’s Human Radiation Experiments report, Stevens’ sister, a nurse, did think it odd that he continued to provide fecal samples long after the experiment.

“Dr Scott also recalled that he never told Mr Stevens what had happened to him: ‘His sister was a nurse and she was very suspicious of me. But to my knowledge, he never found out,’” they explained.

Stevens, Not Stephens

Finding Stephen’s family was a lengthy process for Welsome, not least because when she eventually tracked down his son, it was revealed that his real name was Albert Stevens, not Stephens. After learning what had been done to his father, Thomas shared a curious detail: following his death, somebody had phoned to request Albert’s cremated remains.

The cremains were shipped from the Chapel of the Chimes in Santa Rosa, California, to the Center for Human Radiobiology in 1975, “for the purposes of advancing medical and scientific research and education.” Despite no mention of plutonium in the consent form for their relocation, the examiner found evidence that plutonium was widespread in the skeleton.

When the secret plutonium experiments were eventually held to account, the surviving families of 16 of the 18 patients affected were settled outside of court with cash sums. A “factfinding” assembled by the University of California at San Francisco suggested some of the claimants weren’t part of the plutonium experiment and instead were part of legitimate research into cancer treatments. In the cases where lack of consent was clear, including Stevens, they expressed that “The committee found no evidence that the experiment was designed with malevolent intentions.”

Understandably, the surviving family took a different view.

“The people who did this to my grandfather had only to ask themselves how they would feel if they were in his place,” Welsome writes Steven’s grandson, Bill Holmes, said. “Any code of ethics or scientific experiment involving humans must, it seems to me, begin and end with that very simple question.”

Source Link: Albert Stevens Survived One Of Highest Known Accumulated Radiation Doses In History