Humans like to think we’re unpredictable beings, to a certain extent, governed by free will emerging somehow from physical processes. Well, here’s one weird thing to send you into a linguistics-based existential crisis; most languages appear to follow an equation known as Zipf’s law, and we have no idea why.

Words are used with varying frequency, as you might expect. You have more use for the word “the” than you do for the word “ecumenical” or “phubbing“, for example. But analyzing the frequency of word use in large texts reveals that it closely follows a specific statistical law.

“About 80 years ago, George Kingsley Zipf reported an observation that the frequency of a word seems to be a power law function of its frequency rank, formulated as f(r) ∝ 𝑟𝛼, where f is word frequency, r is the rank of frequency, and 𝛼 is the exponent,” a paper on the topic explains.

To put it simply, the most frequently used word in a language – in English, “the” – is used twice as often as the next most common word, and three times as often as the next, and four times as often as the next, and so on following this power law for a surprisingly long time.

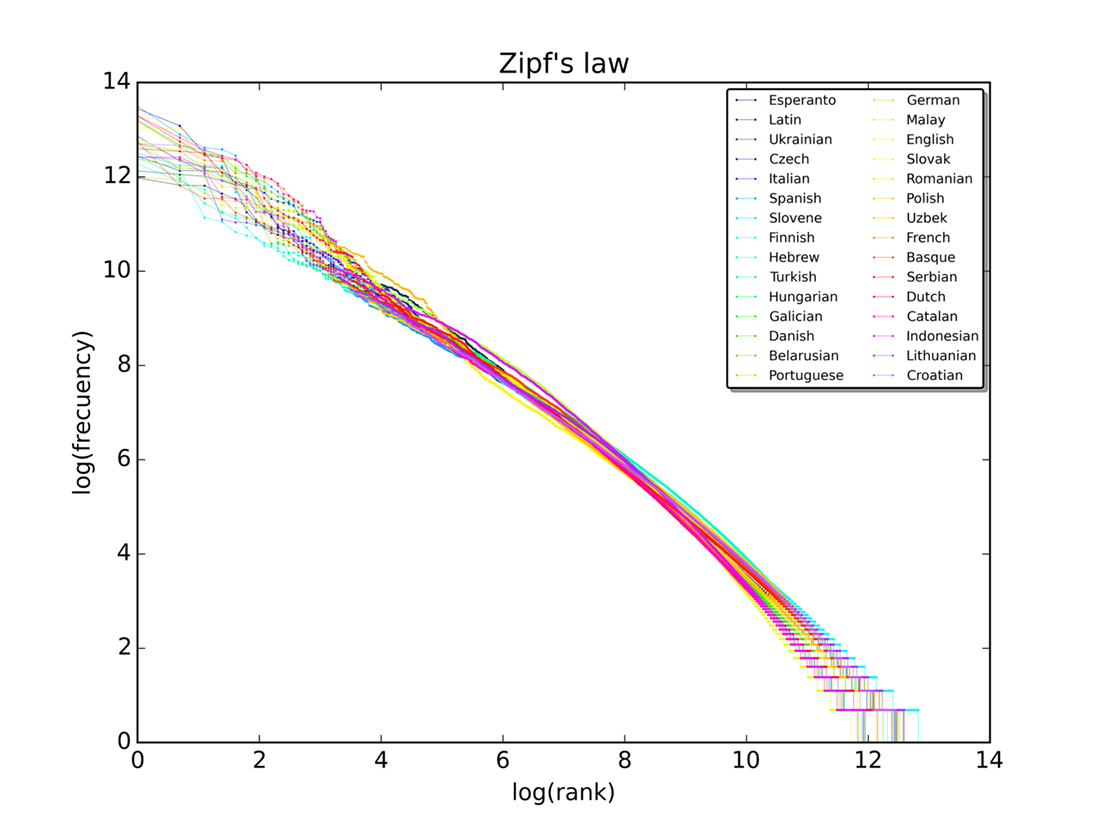

You may think this is some weird quirk of English, but it isn’t. Zipf’s law appears to apply to almost all languages that have been looked into. No matter whether you are speaking English, Hindi, French, Mandarin, or Spanish, the frequency of a word appears to drop off scaling to its popularity rank.

Zipf’s law applies to the first 10 million words in 30 different languages on Wikipedia.

Weirder still, it even applies to languages we haven’t even deciphered yet. Even the words appearing in the mysterious Voynich Manuscript appear to follow this law. And individual texts, if they are large enough, will roughly follow these laws too, with the top-ranked word appearing twice as much as the next etc, etc. Even Charles Darwin can’t evolve his way out of this one, with one analysis finding it applies fairly neatly to his text On the Origin of Species. In fact, it crops up all over the place.

So, that’s pretty weird, no?

“It is worth reflecting on the peculiarity of this law,” a review of the topic explains. “It is certainly a nontrivial property of human language that words vary in frequency at all; it might have been reasonable to expect that all words should be about equally frequent. But given that words do vary in frequency, it is unclear why words should follow such a precise mathematical rule – in particular, one that does not reference any aspect of each word’s meaning.”

There are many potential explanations for the idea, from statistical problems to constraints imposed by human memory and vocabulary. George Zipf himself proposed that the law comes from a balance of effort minimization, with speakers (or writers) attempting to minimize their own effort by using more frequently occurring words, and listeners (or readers) seeking clarity in language from less-frequently used words. An extension of this is that humans attempt to convey meaning as efficiently as possible, tending towards using words that maximize the amount of information they can convey.

Another idea is that more common words tend to become more popular over time as language spreads and develops, leading to a sort of snowball effect. But none are truly accepted as the explanation, and the cause behind it remains a bit of a mystery.

If you would really like to send yourself into a linguistics-based existential crisis, you can even paste your own (long) text/novel/paper into a distribution calculator and see if it obeys Zipf’s law. You might not like how predictable your use of language may appear, but fear not, even Shakespeare’s Hamlet appears to follow it too.

Source Link: Almost All Languages Appear To Follow Zipf's Law, And We Have No Idea Why