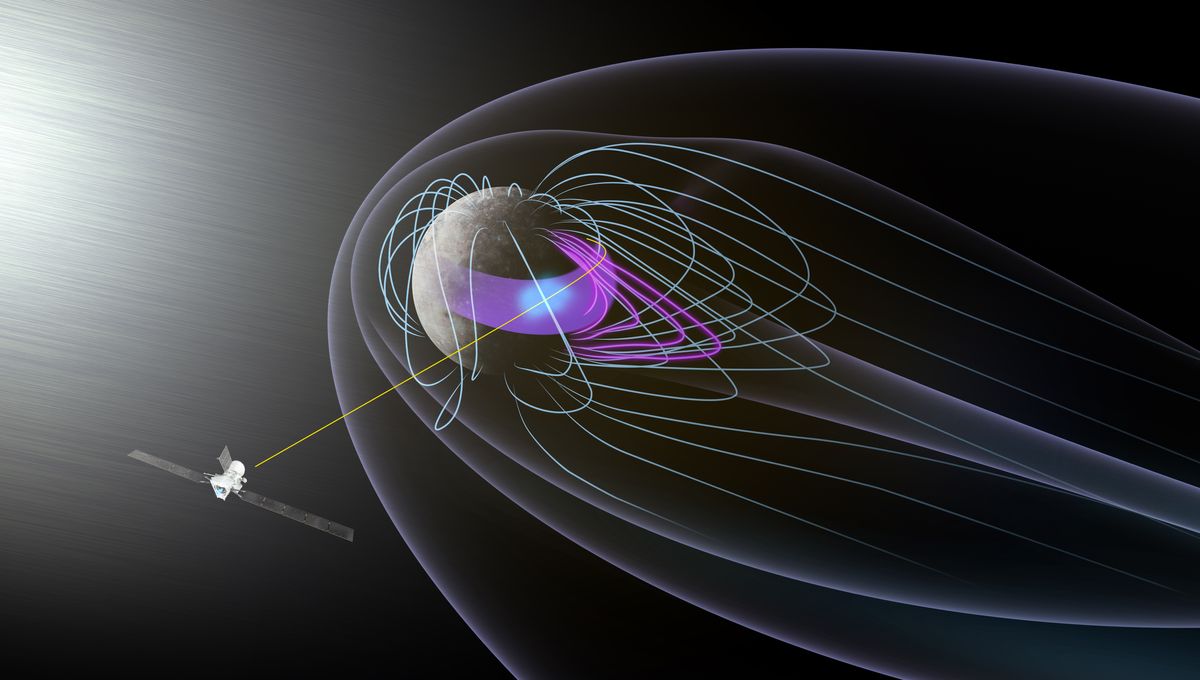

BepiColombo’s June 2023 flyby of Mercury put the spacecraft on the right trajectory to get in orbit around the smallest planet, and it was also a chance to test its science instruments. Even with such a brief window of time, researchers were able to get incredible insights into the planet’s magnetosphere.

Mercury’s magnetic field is complex and dramatically affected by being so close to the Sun. BepiColombo is actually two orbiters in one mission: the European Space Agency-led Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and the Japanese Space Agency-led Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO, or Mio). Dr Lina Hadid, the co-investigator of the Mercury Plasma Particle Experiment (MPPE) suite of instruments active on Mio, used the flyby on June 19 to get some readings of the planet.

“These flybys are fast; we crossed Mercury’s magnetosphere in about 30 minutes, moving from dusk to dawn and at a closest approach of just 235 km [146 miles] above the planet’s surface,” Dr Hadid, who is the lead of MPPE’s Mass Spectrum Analyser, said in a statement. “We sampled the type of particles, how hot they are, and how they move, enabling us to clearly plot the magnetic landscape during this brief period.”

The data collected over those precious minutes revealed that a lot of our expectations for the magnetosphere matched reality, but there were a few intriguing bits that the team did not expect to see.

“We saw expected structures like the ‘shock’ boundary between the free-flowing solar wind and the magnetosphere, and we also passed through the ‘horns’ flanking the plasma sheet, a region of hotter, denser electrically charged gas that streams out like a tail in the direction away from the Sun. But we also had some surprises,” Dr Hadid explained.

“We detected a so-called low-latitude boundary layer defined by a region of turbulent plasma at the edge of the magnetosphere, and here we observed particles with a much wider range of energies than we’ve ever seen before at Mercury, in large thanks to the sensitivity of the Mass Spectrum Analyser designed especially for Mercury’s complex environment,” the former instrument lead Dominique Delcourt added. “BepiColombo will be able to determine the ion composition of Mercury’s magnetosphere in greater detail than ever.”

“We also observed energetic hot ions near the equatorial plane and at low latitude trapped in the magnetosphere, and we think the only way to explain that is by a ring current, either a partial or complete ring, but this is an area that is much debated,” Hadid followed.

Such a ring current is present around Earth, tens of thousands of kilometers from the surface, where particles trapped in the magnetosphere carry an electrical current in a donut-shaped volume around the planet. It is not clear how Mercury has one — something for Mio and MPO to find out in a few years.

BepiColombo had a little thruster problem earlier this year and to make sure that it reached its orbit around Mercury safely, the team had to conduct a daring maneuver and delay arrival. Getting to Mercury without spending a lot of fuel is easier said than done, but slowly and surely this spacecraft is getting there.

The research is published in Nature Communications Physics.

Source Link: An Electrical Donut And Magnetic Horns Spotted Around Mercury During Quick Flyby