A team of researchers and volunteers at the Florida Museum of Natural History have discovered an ancient “elephant graveyard” containing the fossilized remains of a long-extinct ancestor to our modern-day pachyderms. The find may also provide the largest known specimen of the animal ever discovered in Florida.

Sometimes around 5.5 million years ago, a number of gomphotheres, an extinct ancestor to elephants, died in or around a now vanished prehistoric river in northern Florida. Although it is likely that the animals died at different times, some hundreds of years apart, their bodies nevertheless ended up deposited in the same location where they were entombed until early 2022.

At the time, the team found parts of gomphothere skeletons in the Montbrook Fossil Dig, which was nothing special. Fragments and isolated bones had been found there in the past, so there was no reason to suspect that anything unusual was happening. Then, a few days later, volunteers unearthed what appeared to be a huge articulated foot. Subsequent work revealed it to be an ulna and radius belonging to a large gomphothere. Soon, they had recovered an entire skeleton. It was an extremely exciting discovery for the team.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime find,” Jonathan Bloch, curator of vertebrate palaeontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, said in a statement. “It’s the most complete gomphothere skeleton from this time period in Florida and among the best in North America.”

Soon after, however, it became clear that the deceased animal was not alone. In the end, the team recovered entire skeletons from one adult and at least seven juveniles.

More work is needed before the team can accurately determine the animals’ sizes, but Bloch believes the adult specimen was around 2.4 meters tall (8 feet) – with its tusks, the skull measures over 2.7 meters (9 feet) in length. This is about the size of a modern African elephant and represents a record for a local gomphothere specimens.

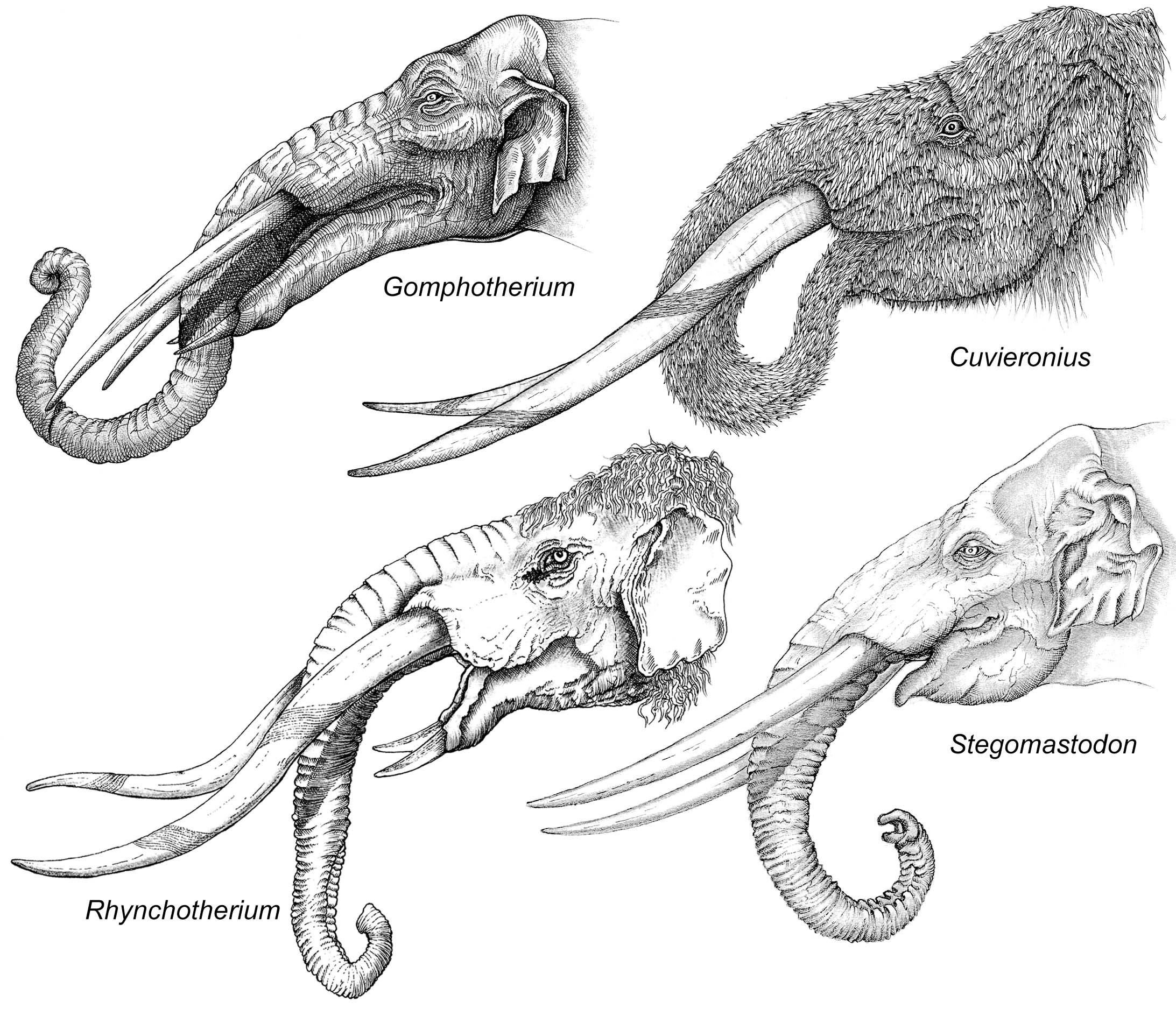

Illustrations of the different genera of gomphotheres, including the Rhynchotherium, which have been found in Florida.

“Modern elephants travel in herds and can be very protective of their young,” explained Rachel Narducci, collection manager of vertebrate palaeontology at the Florida Museum, “but I don’t think this was a situation in which they all died at once. It seems like members of one or multiple herds got stuck in this one spot at different times.”

“We’ve never seen anything like this at Montbrook,” Narducci added. “Usually, we find just one part of a skeleton at this site. The gomphotheres must have been buried quickly, or they may have been caught in a curve of the river where the flow was reduced.”

Gomphotheres, along with modern elephants, are collectively called proboscideans. Relatives of elephants were once abundant across most continents until humans arrived, and gomphotheres were some of the most diverse. These large mammals have an exceptionally long place in the fossil record, spanning over 20 million years. They first emerged in Africa and then spread out across Europe and Asia, eventually crossing the Bering Land Bridge into North America. During this time, they evolved various unique features that allowed them to survive wherever they settled.

“We all generally know what mastodons and woolly mammoths looked like, but gomphotheres aren’t nearly as easy to categorize,” Narducci said. “They had a variety of body sizes, and the shape of their tusks differed widely between species.”

Typically, palaeontologists use tusks as a way to identify a species. The gomphotheres at Montbrook have a spiral band of enamel running along the length of their tusks, which gives them the appearance of a “barber’s pole”. Interestingly, only one group of gomphotheres with this pattern existed at the time, which allowed Bloch and Narducci to identify the species as belonging to genus Rhyncotherium.

“A fossil site in southern California is the only other place in the U.S. that has produced a large sample of Rhynchotherium juveniles and adults,” Bloch said. “We’re already learning so much about the anatomy and biology of this group that we didn’t know before, including new facts about the shape of the skull and tusks.”

The Montbrook discoveries offer exciting prospects for future research and provide an opportunity to learn more about these enormous animals that roamed North America so long ago.

“The best part has been to share this process of discovery with so many volunteers from all over the state of Florida,” Bloch said. “Our goal is to assemble this gigantic skeleton and put it on display, taking its place alongside the iconic mammoth and mastodon already at the Florida Museum of Natural History.”

Source Link: Ancient 5.5-Million-Year-OId “Elephant Graveyard” Discovered In Northern Florida