A study of 724 ancient poems has revealed how far the Yangtze finless porpoise once roamed within the mighty river, allowing scientists to see how far its range has contracted and when that occurred. This may help identify how much threat the porpoise is under, and provide a stretch goal for restoring its ecosystem’s state.

The novelist and chemist C.P. Snow wrote of science and the arts as “two cultures”, and bemoaned the fact that people engaged in one often knew little of the other. He contrasted this with earlier times when figures such as Leonardo da Vinci (and himself) excelled in both. Nevertheless, the arts certainly have a great deal to learn from science, and sometimes it goes the other way.

Fossils are usually the only way scientists can identify a species’ previous range, and they are almost always rare. However, when people love an animal or plant enough to include sightings in their poetry, the situation changes, and a team of conservationists have put that record to use.

Dr Zhigang Mei of the Chinese Academy of Sciences grew up near the Yangtze River where the porpoises are an important part of the local culture. The porpoise has the good fortune to have a face that makes it appear to humans to always be smiling. In the culture around the river’s banks, the porpoises were considered to be positive spirits, able to predict the weather and fish levels. To harm them was considered bad luck.

“Protecting nature isn’t just the responsibility of modern science; it’s also deeply connected to our culture and history,” Mei said in a statement. “Art, like poetry, can really spark an emotional connection, making people realize the harmony and respect we should have between people and nature.”

However, while art’s capacity to serve as a rallying call for the environment gives many artists a sense of porpoise (sorry, had to be done), it is more seldom acknowledged as a tool for scientific research.

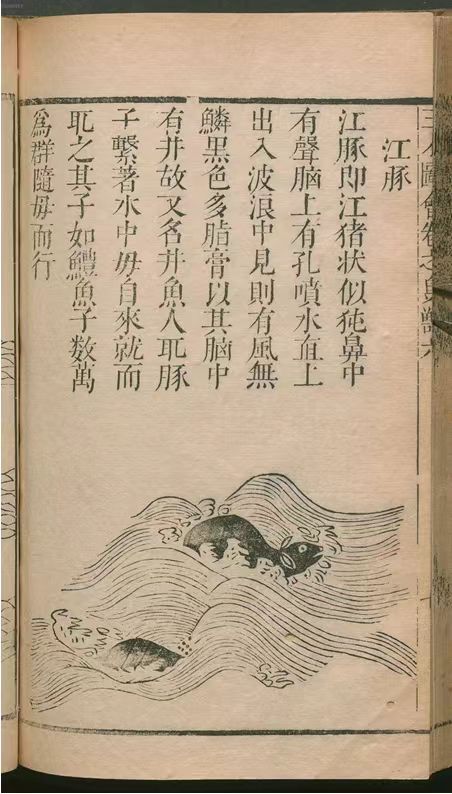

A Ming Dynasty woodblock-printed illustration detailing the Yangtze finless porpoise’s morphology, surfacing postures, and maternal care behaviors.

Image credit: “Sancai Tuhui,” compiled by Wang Qi (1573–1620)

At 6,300 kilometers (3,800 miles), the Yangtze is Asia’s longest river. Although the upper reaches were beyond the Yangtze finless porpoise, it once swam through most of that length, as well as many tributaries. It’s the world’s only freshwater porpoise, although several freshwater dolphins cling on, most of them near the edge of extinction.

When rivers were a primary mode of transport, poets would include sightings of the porpoise from their travels, including Qianlong, the sixth emperor of the Qing dynasty. During his long, 18th-century reign, Qianlong wrote many poems himself and was a patron of poets he liked, while also suppressing work he objected to. (He still got a dinosaur named after him).

The capacities attributed to the porpoises have elements of truth. “Compared to fish, Yangtze finless porpoises are pretty big, and they’re active on the surface of the water, especially before thunderstorms when they’re really chasing after fish and jumping around,” Mei said.“ This amazing sight was hard for poets to ignore.”

In fact, when Mei and co-authors tried to identify the porpoises’ past range based on poems, they found the problem wasn’t a shortage of data, but they possibility some poets were making things up (hard to believe, I know).

“We had to figure out how accurate the poets were being. Some might have been really focused on realism, describing what they saw as objectively as possible. Others might have been more imaginative, exaggerating the size or behavior of things they saw,” Mei said. “So, once we found these poems, we had to research each poet’s life and writing style to make sure the information we were getting was reliable.”

It’s hard to keep smiling when you’ve lost most of your territory, but finless porpoises manage it.

Image credit: Wang Chaoqun

Exactly half the poems included contained information about the location of the sighting, with 78 percent on the main river, 14 percent in tributaries, and 8 percent in Yangtze-fed lakes.

References to the porpoise bloomed over time, from just five during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) to hundreds in the 17th-19th Centuries. However, this had more to do with changes in culture, and poems being more likely to be preserved, than a porpoise boom.

Nevertheless, the poems revealed the porpoise’s range only contracted modestly until late in the Qing dynasty, which fell in 1912. Now, however, it occupies a third less of the main river than it once did, and its range within the tributaries and surrounding lakes has fallen by 91 percent.

The findings are consistent with what other sources suggest, but are important for replication. The decline is thought to be the result of changes to the ecosystem, such as the building of large dams, rather than direct assaults on the porpoise, which remains protected by the historic reverence. The baiji dolphin and the Chinese paddlefish once occupied similar territory to the porpoise, but are now considered functionally extinct.

Further research may reveal how large porpoise collections grew before the river was changed.

“Our work fills the gap between the super long-term information we get from fossils and DNA and the recent population surveys. It really shows how powerful it can be to combine art and biodiversity conservation,” Mei said.

The paper is published in Current Biology.

Source Link: Ancient Chinese Poetry Reveals The 1,400-Year Decline Of World’s Only Freshwater Porpoise