In Bronze Age Greece and Crete, marrying one’s first cousin was commonplace, new research suggests. The “unprecedented” finding marks the first time researchers have been able to peek behind the curtains of ancient marriages in Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece, using genetic material from human bones.

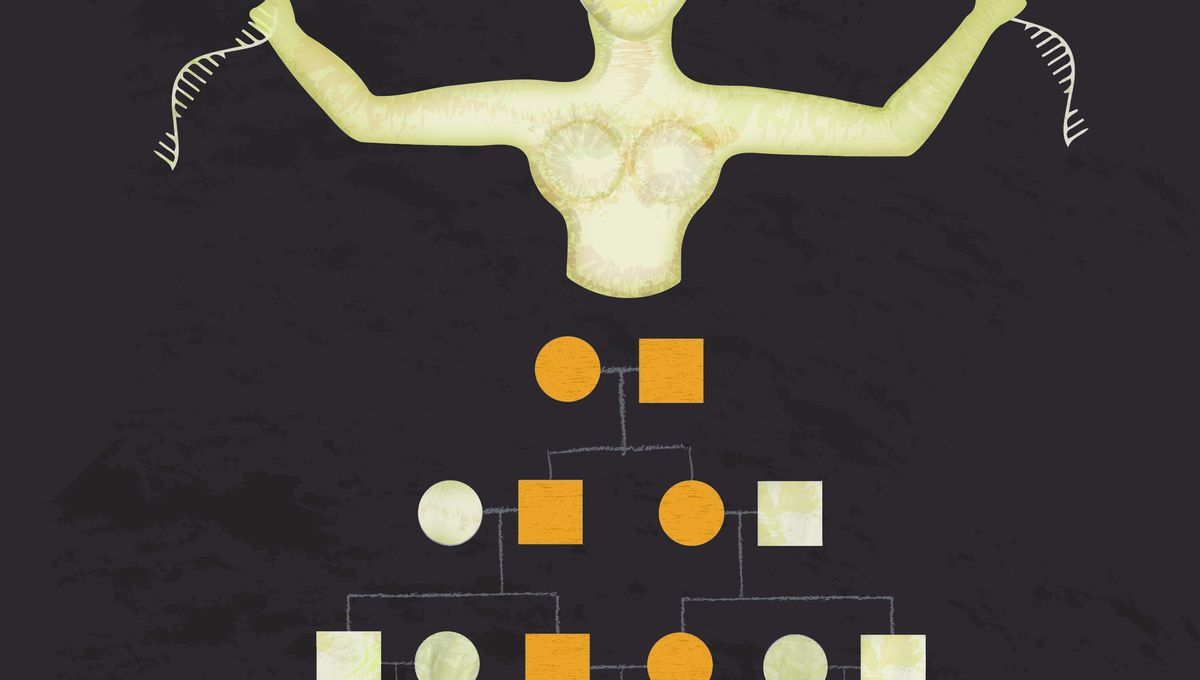

In another first, the researchers were also able to map the biological family tree of a Mycenaean family for the first time.

Analyzing the genomes of 102 people spanning from the Neolithic to the Iron Age in Crete, the Greek mainland, and the Aegean Islands, the team were able to do what no one else had previously managed.

In places such as Greece, the climate makes DNA preservation a challenge. But thanks to recent advances in producing and evaluating ancient genetic datasets, it is now possible to overcome this, meaning the team could construct the first genetic Mycenaean family tree.

Using bones found in an infant grave dated to the Late Bronze Age, they were able to work out the relatedness of seven infants, six of whom were found to be the children and grandchildren of one couple. The seventh child was possibly a first cousin of one of the others. It may be a relatively small family tree, but it is the first of its kind genetically reconstructed for the entire ancient Mediterranean region.

One of the paper’s other, more shocking findings, was that ancient people on Crete, the other Greek islands, and the mainland, often married their own first cousins. Of the Aegean individuals studied, around 30 percent had genetic markers suggesting they were the offspring of two related people, perhaps first or second cousins. The study’s authors write that this discovery was “unprecedented” and “reveals a cultural practice otherwise unattested in the archaeological record”.

“More than a thousand ancient genomes from different regions of the world have now been published, but it seems that such a strict system of kin marriage did not exist anywhere else in the ancient world,” Eirini Skourtanioti, the lead author of the study, said in a statement.

“This came as a complete surprise to all of us and raises many questions.”

Perhaps the most burning of these questions, in many people’s minds, is: why were people so keen on keeping it in the family? The team doesn’t have a definitive answer, but they do offer up some suggestions.

“Geographic isolation, endemic pathogen stress, integrity of inherited land,” are all factors that, historically, may make cross-cousin unions more favorable, the authors write. In this case specifically, they suggest, farming may have played its part:

“Maybe this was a way to prevent the inherited farmland from being divided up more and more? In any case, it guaranteed a certain continuity of the family in one place, which is an important prerequisite for the cultivation of olives and wine, for example,” Philipp Stockhammer, one of the study’s lead authors, hypothesized.

“What is certain is that the analysis of ancient genomes will continue to provide us with fantastic, new insights into ancient family structures in the future,” added Skourtanioti.

The study is published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Source Link: Ancient Greeks Often Married Their First Cousins, Scientists Surprised To Find