Within the depths of an ancient Chehrābād salt mine in Iran, multiple miners met a grisly end thousands of years ago. Over the last few decades, their mummified remains, some of which show the terror they faced at the time of their deaths, have been excavated by archaeologists. Now, recent research has offered fresh insights into the mysteries surrounding these so-called “Saltmen” and the history of the mine that claimed their lives.

The Saltmen mummies

The Chehrābād mine is located in the Douzlākh salt deposit, in the Māhneshān Mountains, which is northwest of where Tehran is today. Most of the Saltmen mummies recovered from the site date back to the Achaemenid Dynasty (550-330 BCE), which was the largest empire of its kind in the ancient world. At its peak, the Achaemenid Empire extended from Anatolia and Egypt across western Asia and northern and central Asia.

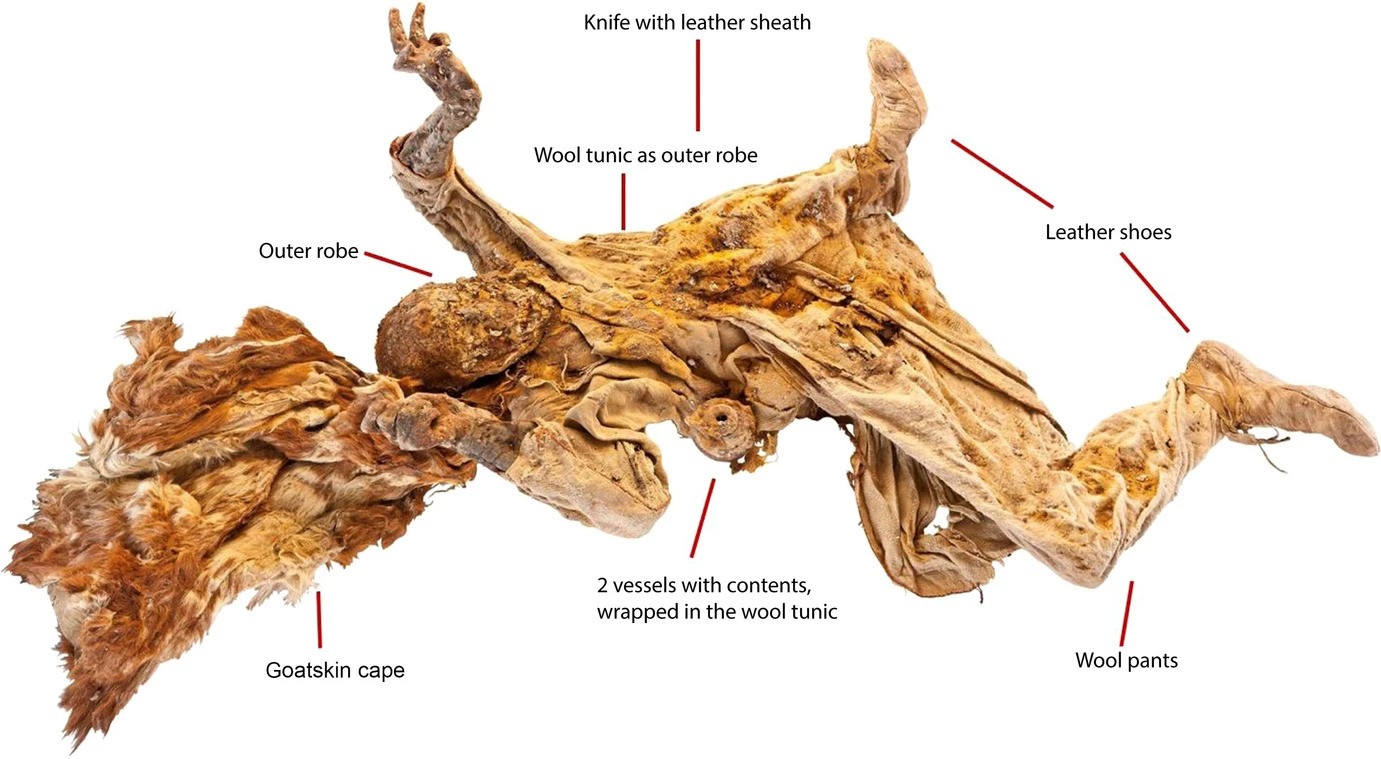

The first mummy fragments were discovered in 1993, which started the first phase of excavations in the salt mountain. This first Saltman’s severed head was preserved with a thick white beard and a single gold earring, and was found with iron knives, a leather boot, and pieces of woollen shorts that were stained with urine and excreta residue.

The severed and mummified head of the first Saltman to be recovered in 1993. The head is now held at the National Museum, Teheran.

This individual is thought to have died around 300 CE, at the time of the Sasanian Dynasty. Then, in 2004, another Saltman was discovered around 15 meters (50 feet) from the first man. By 2010, another six mummies had been recovered from the site. One of the most iconic, and admittedly tragic, mummies belongs to a 16-year-old boy whose preserved remains show him with raised hands, as if he was protecting himself from something.

Subsequent research into the Saltmen shows that they all sustained fractures and compression injuries, suggesting they were crushed by accidents in the mine.

The tragic remains of Saltman 4 reveal the horrible nature of his final moments as his body has become fixed in a state of panic.

In addition, the body of the fifth mummy to be excavated revealed substantial amounts of tapeworm eggs in his intestines, which likely came from a diet of raw and uncooked meat. This result became known as the oldest example of intestinal parasites in Iranian history.

“The salt mummies from the Douzlākh mine are certainly among the most exciting recent discoveries in the archaeology of mining”, Thomas Stöllner, a mining archaeologist, and colleagues explain in their recent review paper that explores the mine’s history.

“Several mining accidents are visible from the bodies, which reveal numerous details of these accidents and the life history of the individuals.”

“The mummies are special for several reasons. Unlike other famous human mummy finds, we are dealing not with a lone individual, but with several comparable people from different working teams. They afford a unique opportunity to study the effects of such preservation conditions on human soft tissue.”

The mummies owe their preservation to the high salt content of the mine, which basically dehydrated their bodies and prevented decomposition.

The life of the mine

Despite the incredible details and evidence provided by the Saltmen mummies, there is much we do not know about the mine itself. We do know that the mine was extensively exploited during the Achaemenid period. At some point around 405 and 380 BCE, however, the mine was abandoned for about 200 years after an accident killed three miners.

The mine was also worked during the Sasanian period, around the second or third century CE. It looks as though the mine remained in operation until sometime in the fifth to early seventh century, when there is evidence of another catastrophe (which resulted in the deaths of Saltman 2 and 6).

There is then evidence that the mine was in use during the Seljuk period (a medieval Turkish empire that ruled the region between 1081 and 1307 CE), and the Ilkhanid period (a medieval Mongol dynasty that ruled Iran between 1256 and 1353 CE).

There is also evidence that the mine was used well into the Middle Islamic period (also known as the Medieval Islamic Empire).

“Over the centuries, extraction locations and the system of extraction changed many times”, the authors write. “As mining shifted to more productive locations, space created during earlier operations could be used for other purposes.”

This complex process means researchers can reconstruct how and when the mine was used by studying its stratigraphy, along with artifacts recovered from the sites.

But how long was the mine in use for prior to the Achaemenid period? This is where the situation becomes even more unclear.

Stöllner and colleagues pulled together information from 18 nearby archaeological dig-sites that spanned from prehistoric contexts to the Islamic period. Their belief being that the Douzlākh “salt dome” would have “assumed a central role in the economic life of rural populations.”

Excavations have recovered evidence of settlements that date back as far as the Chalcolithic or Copper Age (5,000-4,000 BCE), and possibly even the Stone Age. However, just because there were people living in the area during these times does not mean they actively mined the salt from it. At present, there is little evidence to prove they did so.

If these prehistoric communities did exploit the mine, their methods for doing so have been lost to history or were too disorganized to leave a trace.

The study is published in the Journal of World Prehistory.

Source Link: Ancient Iranian "Saltmen" Mummified In Mine 2,500 Years Ago Depicted In New Images