When you think of primates in their natural habitat, your first instinct probably isn’t to imagine them hanging out in the Arctic. But the new discovery of two previously unknown species of prehistoric near-primates, dating back a whopping 52 million years, has shown the unexpected existence of almost precisely that: the oldest evidence of primatomorphans yet identified as living north of the Arctic Circle.

“No primate relative has ever been found at such extreme latitudes,” Kristen Miller, a doctoral student with the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum and lead researcher behind the discovery, said in a statement. “They’re more usually found around the equator in tropical regions.”

But these two species, dubbed Ignacius mckennai and Ignacius dawsonae after pioneering paleontologist Mary Dawson and her colleague and contemporary Malcolm McKenna, were descended from an ancestor with the spirit “to boldly go where no primate has gone before,” Miller said.

Specifically, they went all the way to what is now Ellesmere Island, in Nunavut – the northernmost island in Canada, perhaps best known today for its stunning, albeit quickly disappearing, icescapes and tundras.

Fifty-two million years ago, though, things were very different. The world was 4 million years into the Eocene epoch, which had started with the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a massive global warming event that had made the average global climate about 7°C (13°F) higher than today. From that point on, the temperature had only gotten hotter – and so, far from being the icy wasteland we think of as capping the planet today, the Arctic circle was covered in forests and taiga, and home to a wide range of animals including early crocodiles.

“[The near-primates] were most likely very arboreal – so, living in the trees most of the time,” said Miller.

“But they’re… pretty small,” she explained. “Of course, none of these species are related to squirrels, but I think that’s the closest critter that we have that helps us visualize what they might have been like.”

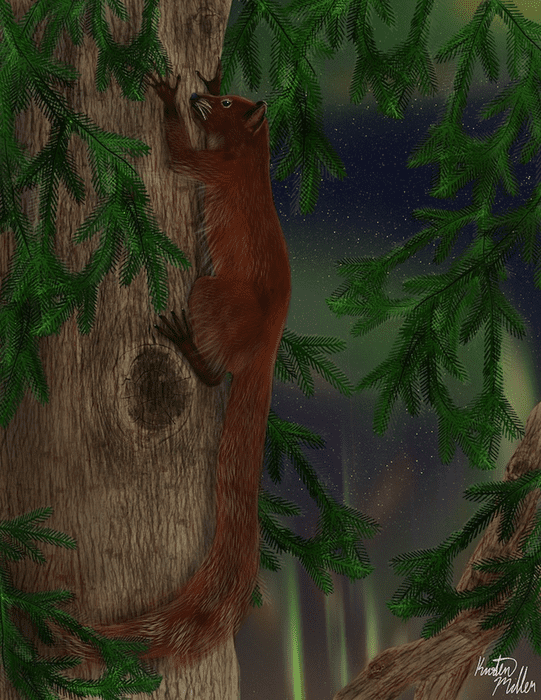

Artist’s reconstruction of Ignacius dawsonae surviving six months of winter darkness in the extinct warm temperate ecosystem of Ellesmere Island, Arctic Canada. Image credit: Kristen Miller, Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas

But while the world may have been warmer back in the Eocene, the laws of physics still applied – which meant that life for the little primate cousins still held some unique challenges. That close to the Earth’s poles, day and night can last for days or weeks on end, and it seems surviving through this strange seasonal rhythm resulted in very specific changes to the creatures’ physiology.

“That, we think, is probably the biggest physical challenge of the ancient environment for these animals,” said Chris Beard, senior curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Biodiversity Institute and Foundation Distinguished Professor of Ecology & Evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas and corresponding author on the project.

“How do you make it through six months of winter darkness, even if it’s reasonably warm? The teeth and even the jaw muscles of these animals changed compared to their close relatives from midlatitudes. To survive those long Arctic winters, when preferred foods like fruits were not available, they had to rely on ‘fallback foods’ like nuts and seeds.”

“Their teeth are just super weird compared to their closest relatives,” agreed Miller, who analyzed high-resolution microtomography of the fossils.

“A lot of what we do in paleontology is look at teeth – they preserve the best,” she explained. “So, what I’ve been doing the past couple of years is trying to understand what they were eating, and if they were eating different materials than their middle-latitude counterparts.”

As fantastic as the discovery of two brand-new prehistoric critters is, it’s not just important for scholars of ancient history. Research into the flora and fauna of the Eocene is increasingly being studied as a proxy for what we may be facing as human-caused climate change continues to alter the planetary ecosystem. Indeed, one study concluded that if human-made carbon emissions continued without restriction, the total amount of carbon dioxide injected into the atmosphere since humans started burning fossil fuels could equal the amount released during the PETM by the year 2159.

“[The discovery] does show how something like a primate or a primate relative that’s specialized to one environment can change based off of climate change,” Miller said. “I think probably what it says is primates’ range could expand with climate change or move at least towards the poles rather than the equator. Life starts to get too hot there, perhaps we’ll have a lot of taxa moving north and south, rather than the intense biodiversity we see at the equator today.”

The findings have been published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Source Link: Ancient Near-Primates Oldest Ever Found Above Arctic Circle