This wall, known as the Muralla La Cumbre, was previously thought to have protected important farmland from invaders, but new research suggests it actually prevented El Niño floods from wreaking havoc.

The ancient earthen wall is about 10 kilometers (6 miles) long and is located in the desert near Trujillo, in northern Peru. It was built near to where the capital city of Chan Chan used to be. This city belonged to the Chimú people (otherwise known as the Kingdom of Chimor) who lived along the coast of northern Peru from around the 9th to the 15th century CE.

Many of us have heard about the different pre-Columbian peoples of South and Central America, such as the Maya, the Incas, and the Aztecs, but the Chimú are often overlooked.

During its day, this civilization was the largest and most prosperous culture in the region and occupied a 1,000-kilometer (621-mile) stretch of coastline that extended into an area of today’s northern Chile. Despite their significance, the Chimú were eventually conquered by the Incas, with whom they had long-standing enmity.

Until recently, it was believed that Muralla La Cumbre was built as a result of these hostilities. It was thought to serve as a barrier to protect the Chimú from invasion.

“According to several accounts written in Colonial times, the descendants of the Inca nobility and the Chimú nobility told the Spanish that both Incas and Chimú had a long lasting war between CE 1400-1450”, Gabriel Prieto, Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Florida told IFLScience. “The wall [near] Chan Chan is then considered part of the defensive strategy to protect themselves from Inca raids.”

However, Prieto has found evidence that Muralla La Cumbre actually protected the area from the devastating floodwaters that appeared in Peru’s wettest phases, known as El Niño.

An El Niño occurs when sea temperatures in the tropical eastern Pacific rise 0.5°C (0.9°F) above normal, resulting in warmer than average weather. These effects tend to occur every few years and peak in December. The term means “the boy”, and is believed to have come from “El Niño de Navidad” several centuries ago when Peruvian fishermen described the weather in reference to the newborn Christ at Christmas.

In some parts of the world, El Niño brings drought, but in Ecuador and northern Peru it results in heavy rains. These waters would have been a significant threat to local communities in the past, especially to the Chimú.

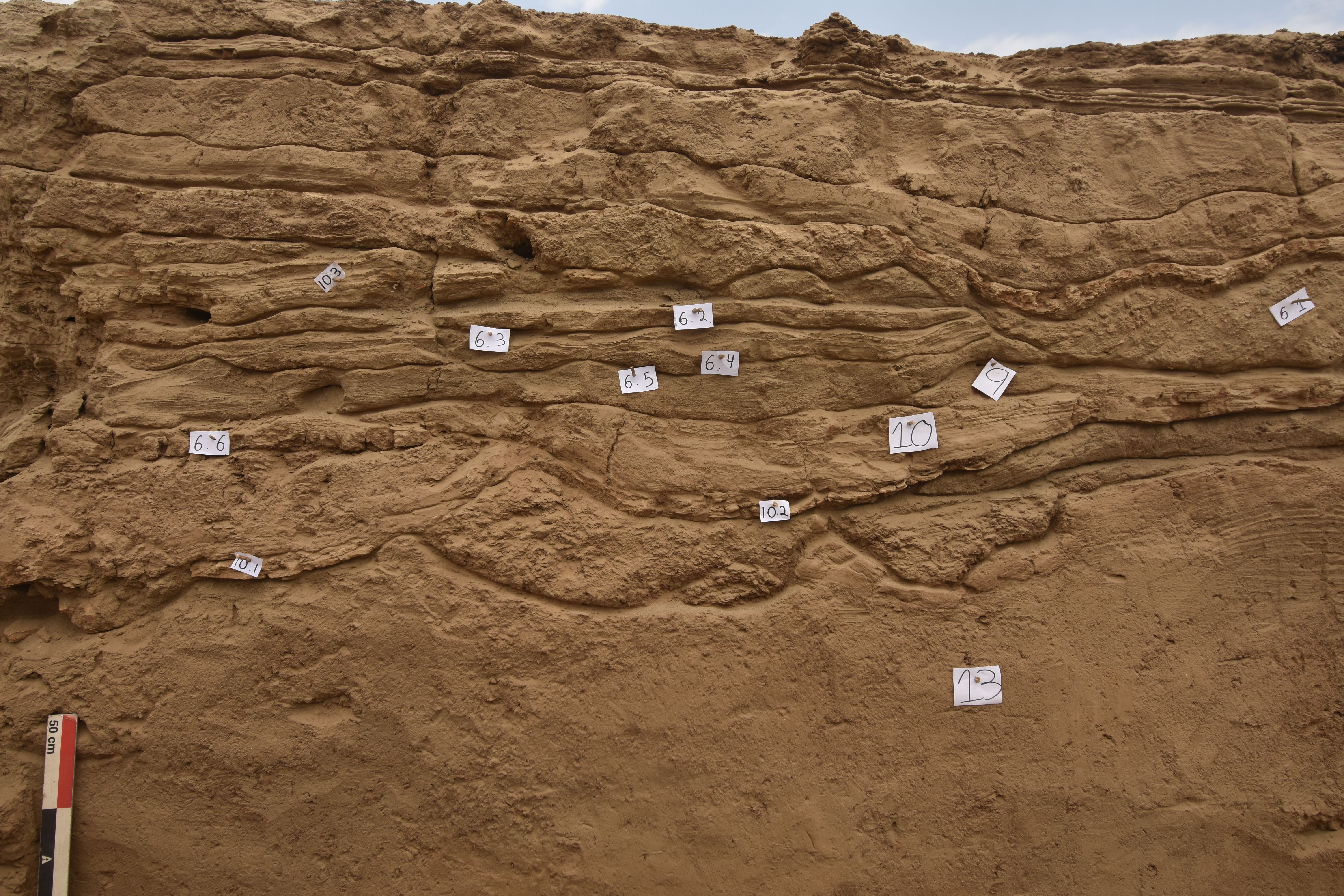

During his research on Muralla La Cumbre, Prieto found layers of flood sediment on one side of the wall, the eastern side, which suggests it was built to protect the farmland to the west.

“I tested an old hypothesis proposed in 2003 by two Peruvian archaeologists: Victor Piminchumo and César Gálvez,” Prieto told IFLScience. “In 2021, I got funding to dig it, choosing a segment of the wall crossing one of the dry ravines and it was very fortunate to find the sediments on the east side.”

El Niño left distinct evidence of flood sediment on the eastern side of the ancient wall.

Image credit: Gabriel Prieto/Huanchaco Archaeological Project

According to results from radiocarbon dating, the lower parts of the wall may have been built around 1100 as a result of El Niño floods.

Prieto’s analysis also found that one of the sedimentary layers dates to around 1450, which coincides with evidence of a mass sacrifice of around 140 children and 200 llamas, which occurred at another Chimú site. For Prieto, this could be a sign that the Chimú knew the dangers posed by the El Niño floods, which caused their rulers to make sacrifices to appease their gods.

This research is significant on several levels, Prieto explained to IFLScience. “It shows that the Chimú, apart from pleasing their gods with human and animal sacrifices, they also made technical and effective infrastructure to cope with the negative effects of [El Niño]. They also created a sort of dam retaining the sediments and rich silts that were possibly used to fertilize agricultural fields.”

It seems the Chimú were far more advanced in terms of their technologies than is often appreciated, especially in relation to their “hydraulic infrastructure”, which helped them cope with intense climate anomalies like those caused by El Niño. This is “something that modern nations like Peru are still suffering for not paying enough attention to simple technology with effective results,” Prieto added.

A paper detailing Prieto’s research has been accepted for publication and will be published soon.

Source Link: Ancient Wall May Have Been Built To Protect From El Niño Floods