As the northern hemisphere suffers through a summer that is breaking heat records like the proverbial bull in a china shop, something even more extreme is happening at the other end of the world. Despite being locked in near-constant darkness, the waters off Antarctica are struggling to form ice. The event is so extreme, in contrast to anything we have seen before, that scientists calculate it would only happen once every 13 billion years if the planet’s temperature were stable. For it to be even close to likely requires the world to be heating up at a rate that may never have happened before.

Until the 1970s our knowledge of the extent of sea ice depended on ships visiting specific locations, which meant Arctic estimates were patchy and Antarctic data barely existed. Since then, satellites have provided a reliable estimate of the scale of sea ice every day. The Arctic data has shown a clear pattern of decline over that time, losing about 13 percent per decade.

The waters around Antarctica were a different story, however, one that climate change deniers loved to point to, since until the last decade no clear pattern was visible. Recently, however, southern waters have been catching up in the very undesirable race as to which can lose ice fastest.

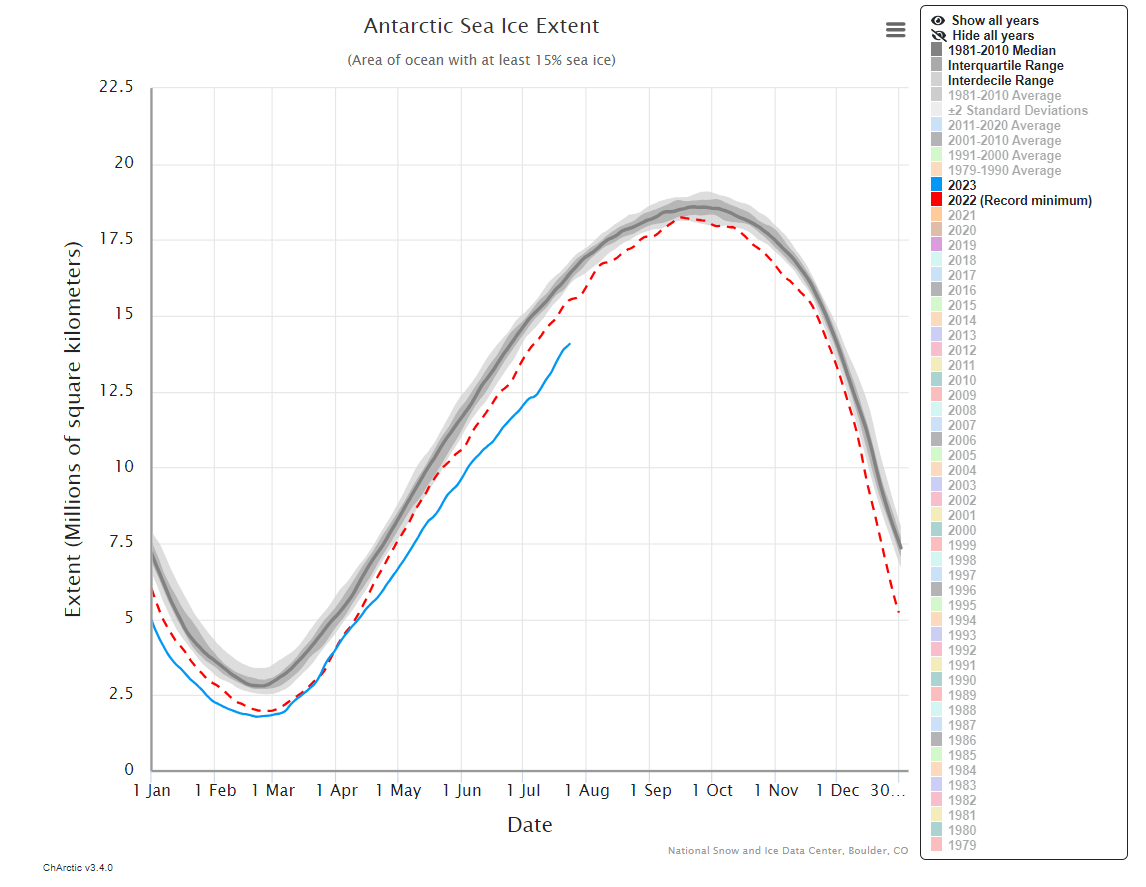

It’s the southern winter, so sea ice is rising, but nothing like as fast as last year’s previous record low, let alone the norm.

Image credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center

Nothing, however, prepared glaciologists for this year. Almost every day in July has broken the previous world record for hottest average temperature, but the size of the break looks puny compared to what is happening around the shores of Antarctica.

The graph below tells the story.

As you might have guessed, the red line is the last seven months, while the others trace out previous years. However, the scale is not in square kilometers of ice – instead, it measures standard deviations from the average for each day of the year over a 30-year measuring period.

That means that a score of -2 would be expected to happen once every 20 years under unchanging conditions. It’s therefore not surprising over a 34-year sample that the line has been crossed several times, sometimes briefly. For the first three months of the year, that was approximately where 2023 was too, although even that set records. Then things went haywire. We now have almost 2.5 million fewer square kilometers of Antarctic sea ice than normal for this time of year, an area the size of Algeria, Africa’s largest country.

The four standard deviation line, or a four-sigma event as physicists call it, should be crossed once every 10,000 years on a chart like this. More often indicates changing conditions.

The ABC reported this year’s ice extent as a five sigma event, which would be expected once in 7.5 million years, but either they were using the data from weeks ago, or understated the situation so as not to appear ridiculous. As the chart shows, we are now at a value of -6.4. That, as retired Professor Eliot Jacobson noted, should only happen once in every 13 billion years with a normal distribution in a constant environment.

Of course the situation is anything but constant. The world is getting hotter, and that means we should expect more years of low sea ice. Nevertheless, you’d be hard pressed to find a scientist who predicted anything this low.

On land a loss of ice can indicate atmospheric warmth, but could also be from lower precipitation or even (in some places) volcanic activity. At sea it has to be warmer waters, air, or both.

Dr Edward Doddridge of the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies told the ABC, “To say unprecedented isn’t strong enough.”

Ice reflects a lot more sunlight than open water. Currently there is barely any light to reflect, but if there is no recovery by spring, absorbed light will heat the Southern Ocean, setting off a vicious spiral.

Currents affect sea ice, but sea ice also drives currents, bringing nutrients to the surface that drive the marine food chain. Krill, on which everything from whales to penguins feed, depend on algae beneath the ice. A winter like this could be catastrophic for many species, although the effects may take months to show.

A forum on the possible consequences of such a catastrophic collapse was held just three weeks ago.

Bad as the consequences of this event will be, the causes may be even more serious. To get an event so far outside the norm is hard to square, not only with a static climate, but with most climate models’ predictions. Things may be getting worse faster than those models could handle.

It will be a while before scientific publications catch up with what has happened and fully explain it, but as the scientists in the video show: we can’t wait for that to act.

Source Link: Antarctica’s Low-Ice Winter Should Only Happen Once Every 13 Billion Years