On October 31, NASA announced that astronaut Thomas Kenneth Mattingly, a key player in ground control efforts to bring the damaged Apollo 13 spacecraft safely back to Earth, had died aged 87. It seems a fitting time to explore what actually happened on the Apollo 13 Moon mission and how close it came to disaster.

Mattingly, known by most as Ken or TK, played a leading role in the development of the Apollo spacesuit and backpack, and was supposed to be on board the ill-fated Apollo 13. However, in the run-up to the mission, backup lunar module pilot Charles Duke exposed the crew to German measles. Without immunity, Mattingly was replaced by backup Command Module Pilot John “Jack” Swigert with just days to go before launch.

This wasn’t the only problem prior to the mission. Ahead of the launch of Apollo 10, the secondary oxygen tank was removed for modification and accidentally dropped around 5 centimeters (2 inches) in the process. A replacement for Apollo 10 was found, but the tank was eventually used for the Apollo 13 service module. Before launch, the tank was tested and found to have dropped to 92 percent capacity. NASA’s test director ordered that the remaining liquid oxygen within the tank be boiled off using the electrical heater inside it.

“The technique worked, but it took eight hours of 65-volt DC power from the ground support equipment to dissipate the oxygen,” according to NASA. “Due to an oversight in replacing an underrated component during a design modification, this turned out to severely damage the internal heating elements of the tank.”

This was likely what caused the damage to the tank, which would cause the crew a headache/mortal terror later on. Though the tanks had been redesigned to run off 65-volt DC power at the Kennedy Space Center, heater thermostatic switches inside the number 2 tank had been overlooked and were designed to run off the 28-volt DC power of the command service module.

It is believed the switches welded shut, allowing the temperature within the tank to rise locally to over [538 celcius] 1,000 degrees F,” NASA explains. “The gauges measuring the temperature inside the tank were designed to measure only to 80 F [27 Celsius], so the extreme heating was not noticed. The high temperature emptied the tank, but also resulted in serious damage to the teflon insulation on the electrical wires to the power fans within the tank.”

For the first few days of the mission to the Moon, it mostly looked to be running smoothly. Fifty-five hours into the trip, the crew participated in a live broadcast to Earth, signing off with “This is the crew of Apollo 13 wishing everybody there a nice evening, and we’re just about ready to close out our inspection of Aquarius and get back for a pleasant evening in Odyssey. Good night.”

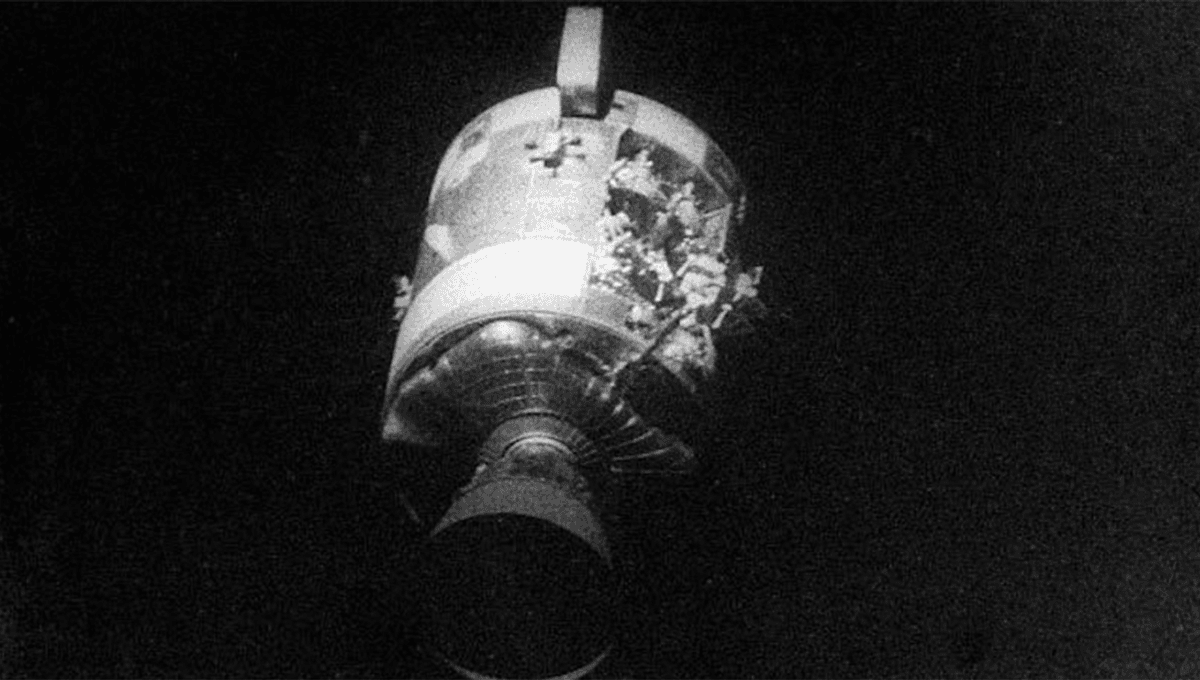

Nine minutes after the broadcast ended, the number 2 tank exploded in the service module, damaging a line or valve in the number 1 oxygen tank in the process, and causing it to lose oxygen. The first they were aware of the situation came when astronaut Jim Lovell (played by Tom Hanks in the movie, who got to utter the immortal but slightly wrong “Houston, we have a problem,” line) noted that they were “venting something out into the… into space.”

For those not familiar with spaceflight or being alive, oxygen is kind of important to both. As well as needing it for the usual purpose (breathing), damage to oxygen tank 1 meant that the use of fuel cells was reduced. They were in danger of being left adrift in space, as their oxygen ran out and they slowly suffocated, without water to quench their thirst either.

The crew moved into the lunar landing module Aquarius, shutting the door to the other modules and using it as a “lifeboat“. Though the module was cold – it was not designed for long-term travel and did not have a heating system – it was determined that the best course of action was to continue the spacecraft’s course, looping around the Moon and firing thrusters at key moments in orbit in order to return to Earth. The team remained crammed inside Aquarius, as some of their rations froze and became inedible, rationing water for the entire journey home.

As they returned home they (thankfully and annoyingly) continued to breathe, raising carbon dioxide levels to dangerous levels. The craft used lithium hydroxide canisters to remove CO2 from the air, but these square canisters were not compatible with the round openings of the Aquarius module. Ground control figured out a system, not too dissimilar to Homer Simpson using a carbon rod to shut a space shuttle door in The Simpsons, by attaching the square canister to the Aquarius system using plastic bags, tape, and cardboard.

The final problem was that their lifeboat was not designed to enter Earth’s atmosphere. However, this was easily solved by the crew climbing back into the command service module and powering it up once more for re-entry.

“He stayed behind and provided key real-time decisions to successfully bring home the wounded spacecraft and the crew of Apollo 13 – NASA astronauts James Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise,” NASA said of Mattingly, who went on to fly the command service module on board Apollo 16, when his death was announced.

“[His] contributions have allowed for advancements in our learning beyond that of space. He described his experience in orbit by saying, ‘I had this very palpable fear that if I saw too much, I couldn’t remember. It was just so impressive.’ He viewed the universe’s vastness as an unending forum of possibilities. As a leader in exploratory missions, TK will be remembered for braving the unknown for the sake of our country’s future.”

Source Link: Apollo 13: What Actually Happened On NASA’s Near-Disaster Moon Mission