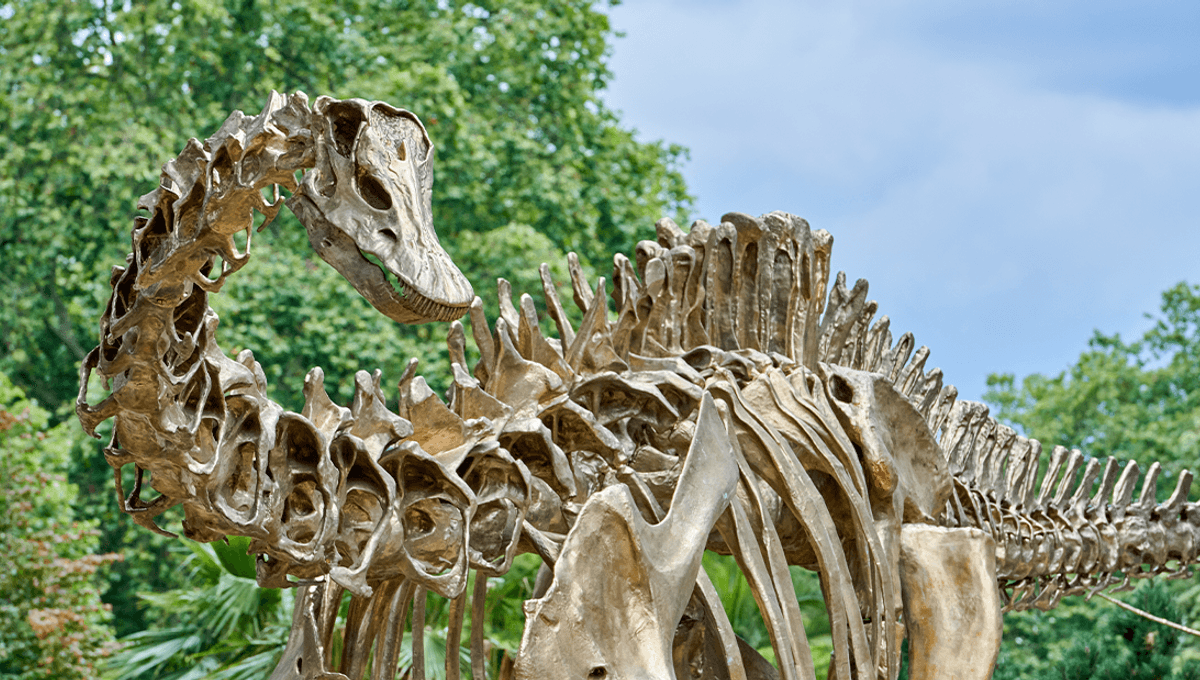

Observing the wonders of the natural world is a pretty incredible experience, from beluga whale migration live streams to visiting your zoo of choice. But what about the wonder of long-dead species that roamed planet Earth millions of years ago? IFLScience took a trip down to the Natural History Museum, London to learn all about their shiny, new bronze Diplodocus, Fern, and just what goes into making dinosaur specimens for display.

Standing in front of a giant bronze Diplodocus that greets visitors in the museum’s brand-new Jurassic Gardens, Professor Susie Maidment, a palaeontologist at the museum, explains just what goes into creating a dinosaur specimen on display. Fern is a marvel, 22 meters long and 4 meters high, but is also a replica of the world-famous Dippy the Diplodocus that greeted visitors in the museum’s main entrance hall for nearly 40 years. However, Fern has been made even more scientifically accurate and improved thanks to new techniques and knowledge that didn’t exist when Dippy first arrived in London in 1905.

The original Dippy was discovered in Wyoming, America in 1899, when millionaire businessman Andrew Carnegie set his sights on acquiring the bones for display in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. However, are the remains of long-dead creatures even bones anymore? When a paleontologist or an amateur fossil hunter finds a dinosaur skeleton in the wilderness what are they actually finding and what then goes on display?

“We find fossilized bone, these will be a combination between actual bone tissue and minerals that have infiltrated the bone over the millions of years that it’s been buried and have precipitated out and replaced some of the bone,” Prof Maidment told IFLScience.

Inside a museum, what you witness can be a combination of those fossilized bones and replicas for a variety of reasons. Not all skeletons can go on display, some are of more scientific value to study, so museums around the world make replicas to showcase the skeletons to the public. Legally some bones must also remain in the country they were found in, so creating replicas is a great way to showcase species to a wider audience.

Sophie the Stegosaurus, which greets visitors at the Museum’s second entrance, is the most complete Stegosaurus in the world, and most of what you see there is real bone, Maidment told IFLScience. The real skull is kept behind the scenes, however, as it is in pieces and instead of sticking it together for display, the scientific value is greater for researchers who can study it in detail, so the head on display is a 3D printed replica.

Dippy – and now Fern – is a complete replica of Carnegie’s Diplodocus with the main body made of around three separate skeletons and the skull from many more. In fact, originally Dippy’s back legs were also used as the front legs because scientists didn’t know what their front feet looked like, but don’t worry they have since been replaced.

To make a replica of the specimens, older casts like Dippy would be made using plaster-of-Paris to cover each bone which would be used to create a detailed mold. This would then be filled with resin or plastic to replicate each piece.

“In the old days you’d take the bones and cover it in Latex or rubbery type liquid that would solidify, you’d then peel it off the bone and put a plaster-of-Paris inside it, to make an exact replica,” Maidment explained.

However, times have moved on and new technology like 3D printing allowed all of Dippy’s 292 bones to be scanned and molds created to cast Fern in more weather-resistant bronze for its place in the museum gardens. While creating a bronze dinosaur like Fern was a technical challenge, 3D printing also gives scientists more flexible materials that can be more accessible when working with a lifesize model of a 30-ton animal.

Source Link: Are Dinosaur Skeletons In Museums The Real Thing?