Missions to Mars have many obstacles to overcome, and perhaps chief among them is the danger astronauts will not be able to perform their duties after too long in microgravity. However, a preliminary model suggests the average healthy astronaut probably will cope with the weak Martian gravity, provided they stick to their exercise routine en route. The same model is being developed further in the hopes it will provide a personalized indication of safety, both for Martian missions and shorter trips by space tourists.

In the journal npj Microgravity, an Australian National University team led by Dr Lex van Loon note: “Around 80 percent of astronauts returning after long-duration space flight experience symptomatic orthostatic intolerance” on encountering gravity again. In other words, just standing up can make their heart rate shoot up, inducing symptoms such as light-headedness, fatigue, and sometimes fainting.

That’s an acceptable consequence of seeing the world from orbit when world-standard medical care is available the moment you land. It’s more of a problem for someone further from the rest of humanity than anyone has ever been, and the only assistance in a crisis is a fellow astronaut experiencing the same thing.

Landing on Mars will be a risky enough endeavor as it is – if the astronauts can’t stay upright, safely things will get ugly.

Fortunately, the Martian gravity is not much more than a third of Earth’s, so it could provide a much more gentle introduction than landing on some uninhabited part of our own world. What no one has known until now was whether that would be enough.

Van Loon and co-authors think that it is. They set out to model the effects that cause orthostatic intolerance and to see how a typical fit astronaut would cope after 6-7 months between worlds. Their conclusion is that most would manage, although they admit we currently only know that for male astronauts – there haven’t been enough female astronauts on long space missions to provide a sufficient sample. Then again, van Loon noted the women who have come back have usually recovered faster because far more of them have stuck to their exercise routine while in space.

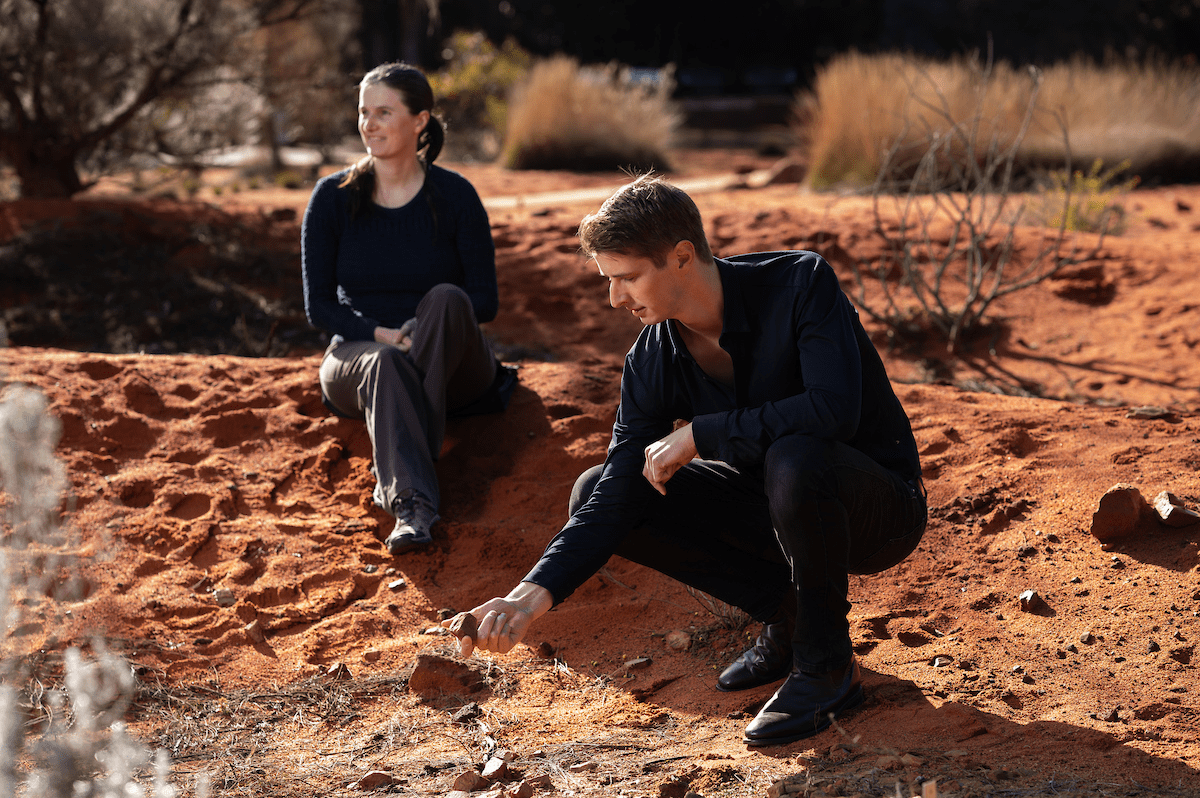

Dr Lex van Loon and Dr Emma Tucker at the Red Centre Garden, Australian National Botanic Gardens in Canberra, pretending Australia’s red soils are Mars. Image Credit: Tracey Nearmy/ANU

The return journey might be a different matter, van Loon told IFLScience. Having spent at least a year and a half away from Earth’s gravity, and only experiencing much force for the middle third, astronauts might be hit hard. However, the team is much less worried about this, given the facilities available to assist returning heroes.

The authors hope to develop the model further, identifying the characteristics that would put an individual at risk on such a mission. The same process could also be applied to prospective tourists keen to spend a few weeks in space. “With the rise of commercial space flight agencies like Space X and Blue Origin, there’s more room for rich but not necessarily healthy people to go into space,” van Loon said in a statement.

The problem occurs because the heart becomes used to not having to work against gravity, which coauthor Dr Emma Tucker said; “Triggers a response that fools the body into thinking there’s too much fluid,” leading to dehydration. Moreover, van Loon told IFLScience, “There are problems with blood clots in the brain and vision can be affected.”

Science fiction books and films once dismissed the problem by assuming spaceships would make artificial gravity, either through constant steady acceleration/deacceleration or by rotating for centrifugal force. Van Loon told IFLScience; “There’s a group in Europe lobbying for money to test such a thing,” but for the moment the centrifugal idea looks too expensive for early Mars missions. Consequently, making sure the astronauts have the right stuff remains essential.

Source Link: Astronauts Probably Won’t Faint On Mars Arrival