Years ago, astronomers believed they had found a planet forming around a nearby star called Fomalhaut. This was very exciting as the planet was imaged directly, the first time that had happened. A few years ago, however, astronomers discovered it was not a planet, but a cloud of debris from a collision in the star system. Even more excitingly, scientists have now captured another collision in the same system, making these the first collisions directly imaged in a solar system that isn’t our own.

Astronomers first found the planet, formerly Fomalhaut b, in Hubble observations from the 2000s while looking for evidence of debris left over from planet formation in the dusty debris belt around Fomalhaut. Paul Kalas, adjunct professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, spotted a bright spot in the belt in 2004 and 2006 and concluded it was a planet. Follow-up observations were carried out until 2014 when Fom b was nowhere to be seen.

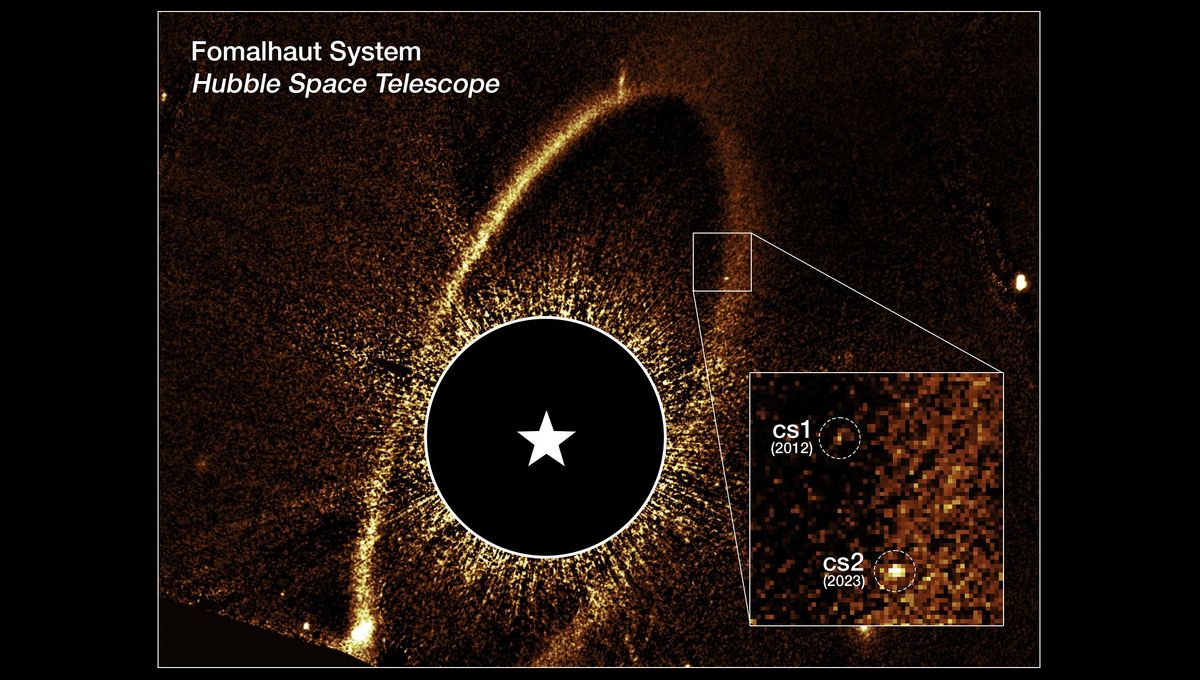

Kalas concluded that instead of a planet, it was more likely a dust cloud created by the collision between small bodies known as planetesimals. In 2023, the bright spot, now known as Fomalhaut cs1, was no longer visible with Hubble, but lo and behold, a brand new bright spot was detected. In a new paper, Kalas and colleagues argue that what they have dubbed Fom cs2 is also a collision, and supports the idea that cs1 is a debris cloud.

“This is a new phenomenon, a point source that appears in a planetary system and then over 10 years or more slowly disappears,” Kalas, who is first author on a new paper on the 2023 observations, explained in a statement. “It’s masquerading as a planet because planets also look like tiny dots orbiting nearby stars.”

The Fomalhaut system is a window into a fledgling planetary system. This is a window onto what our own Solar System might have been like, filled with planetesimals that, after collisions and aggregations, became fully formed planets. The team estimates that about 300 million objects similar to the ones that caused cs1 and cs2 exist around Fomalhaut.

“We just witnessed the collision of two planetesimals and the dust cloud that gets spewed out of that violent event, which begins reflecting light from the host star,” Kalas said. “We do not directly see the two objects that crashed into each other, but we can spot the aftermath of this enormous impact.”

Observing two powerful collisions in just 20 years is either very lucky, or these collisons actully occur more frequently than we thought, which has consequences for our predictions of how planets form.

“Fomalhaut is much younger than the Solar System, but when our Solar System was 440 million years old, it was littered with planetesimals crashing into each other,” Kalas said. “That’s the time period that we are seeing, when small worlds are being cratered with these violent collisions or even being destroyed and reassembled into different objects. It’s like looking back in time in a sense, to that violent period of our Solar System when it was less than a billion years old.”

Thanks to these new and past observations, researchers were able to estimate that the planetesimals in both collisions were at least 60 kilometers (37 miles) across. That is over four times larger than the Chicxulub impactor that hit Earth 66 million years ago, ending the Cretaceous and non-avian dinosaurs.

“The Fomalhaut system is a natural laboratory to probe how planetesimals behave when undergoing collisions, which in turn tells us about what they are made of and how they formed,” said co-author Mark Wyatt, a theorist and professor of astronomy at the University of Cambridge. “The exciting aspect of this observation is that it allows us to estimate both the size of the colliding bodies and how many of them there are in the disk, information which it is almost impossible to get by any other means.”

Kalas will use both JWST and Hubble to observe Fomalhaut over the next three years. Observations this summer with Hubble show that cs2 is still visible and 30 percent brighter than cs1. The scientists will track how it changes to see if it expands in size and work out its orbit.

The study is published in the journal Science.

Source Link: Astronomers Catch Incredible First Direct Images Of Objects Colliding In Another Star System