A neutron star 11.400 light-years away is doomed to eventually collide with its giant companion. By the time it does, the giant will also be a neutron star, setting off an explosion that will seed the galaxy for thousands of light-years around with precious metals, known as a kilonova.

The makeup of the universe depends on extremely rare events. Supernovas, which occur roughly once a century in galaxies as large as the Milky Way create and disperse metals that go on to form the basis of future planets. Some of the rarer metals require something even more exotic, the collision of two neutron stars, first observed in 2017 when gravitational waves alerted us to one of the most important events in astronomical history.

Neutron stars are the result of supernovas of stars with masses 10-25 times the mass of the Sun. Although thousands of them exist in the Milky Way, two seldom orbit each other so the discovery of a future such pair by the SMARTS 1.5-meter Telescope in Chile, announced in Nature, is a stunning achievement. Even some neutron stars in mutual orbits will never form a kilonova if the distance between them is too great. Consequently, the discovery that the system known as CPD-29 2176 is tight enough to eventually collapse turns a big discovery into something truly epic.

NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory first raised the possibility there was something interesting about CPD-29 2176 when it observed a magnetar-like burst in 2019. Follow-up observations using SMARTS revealed a neutron star orbiting a massive main-sequence star.

Although the neutron star’s progenitor was once the more massive of the two, it shed much of its mass to its companion during its red giant phase and the supernova event several million years ago.

Crucially, the main sequence star is of the right mass to eventually become a neutron star itself, and eventually the two will collide.

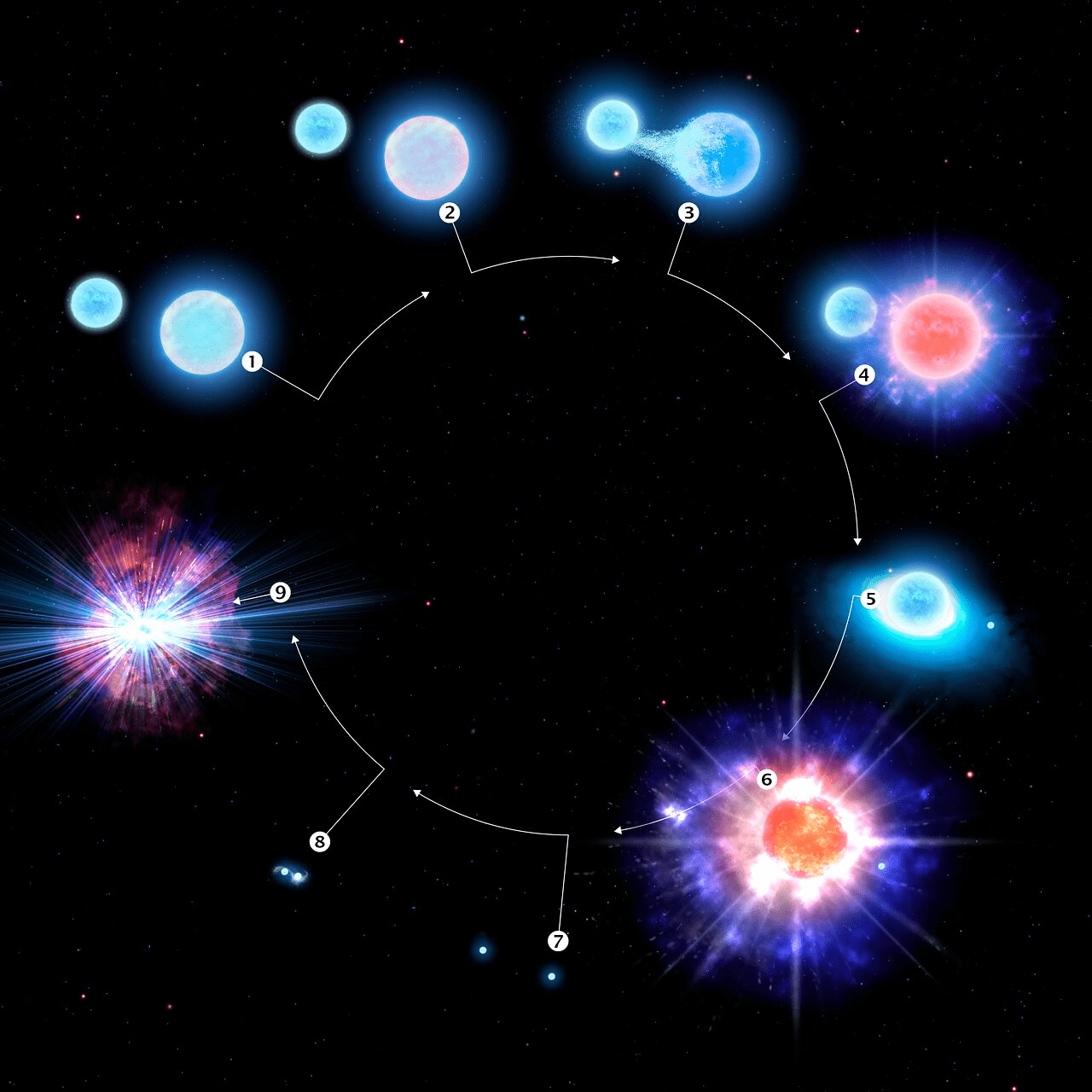

The evolution of CPD-29 2176, 1, two massive blue stars form in a binary star system. 2, the larger star nears the end. 3, the smaller star siphons off material from its larger, more mature companion,.4, the larger star forms an ultra-stripped supernova 5, Currently the resulting neutron star is siphoning off material from its companion. 6, The companion star also undergoes an ultra-stripped supernova. 7, a pair of neutron stars remain. 8, the two neutron stars spiral into toward each other, 9 A kilonova, the cosmic factory of heavy elements in our Universe. Image Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/P. Marenfeld

Don’t expect anything soon, however. First, the surviving star needs to explode as a supernova, something that is at least a million years off. Then the two orbits need to decay as energy is carried off in gravitational waves until they meet.

One reason kilonovas are so rare is that only a small minority of stars are the right size to become neutron stars. An additional twist is that many supernova explosions kick companions stars away so powerfully they end up shooting across the galaxy – sometimes escaping entirely – preventing any collision.

However, one class of explosion, known as an ultra-stripped supernova, has less explosive force, allowing the two stars to stay in orbit. Ultra-stripped supernovas occur when stars orbit closely enough that the outer layers get pulled off prior to the explosion. This must have happened to CPD-29 2176’s neutron star pre-explosion, allowing it to stay connected to its companion. Now the circumstances are right for the same thing to happen the other way around.

It may be a stretch to imagine our current civilization surviving long enough to see the CPD-29 2176 kilonova, but observing the system in its current state could still teach us a lot.

“For quite some time, astronomers speculated about the exact conditions that could eventually lead to a kilonova,” Dr André-Nicolas Chené of NOIRLsb said in a statement. “These new results demonstrate that, in at least some cases, two sibling neutron stars can merge when one of them was created without a classical supernova explosion.”

The combination of circumstances required to create paired neutron stars that will eventually collide are so unlikely the authors call CPD-29 2176 a one-in-10-billion system. Still, that makes for roughly 10 in the galaxy, which is an upgrade on previous thinking. “Prior to our study, the estimate was that only one or two such systems should exist in a spiral galaxy like the Milky Way,” Chené said.

Ten feels almost common by comparison. Now the quest is on to find the other nine.

The paper is published in Nature.

Source Link: Astronomers Discover A “One-In-10-Billion” Kilonova-In-Waiting For First Time