Stories told by Indigenous Tasmanians to white settlers appear to describe the flooding of Bass Strait, which occurred 12,000 years ago, as well as the location of the stars at a similar time. Records of Tasmania’s Indigenous oral traditions are scant, but with the exception of some much more speculative connections, these appear to be the oldest known accounts describing real events.

When British settlers arrived in 1803, the Palawa (Indigenous Tasmanians) had lived in almost total isolation since the flooding of Bass Strait, which separates Tasmania from mainland Australia, at the end of the last glacial maximum. Besides being particularly vulnerable to external diseases, the Palawa suffered one of the most systematic extermination campaigns of indigenous peoples anywhere, with most native inhabitants either murdered or deported to Flinders Island.

George Augustus Robinson was assigned to “mediate” between the invaders and the people being rounded up. While not an anthropologist, he did record some of the culture he was helping destroy, and Robinson’s accounts include what appear to be tales of the flooding that cut Tasmania off from mainland Australia.

Since the separation occurred 11,960 and 12,890 years ago this would require stories to have been handed down for 400-600 generations.

Appropriately, a claim that large has been treated with skepticism by anthropologists, but an interdisciplinary team led by Dr Duane Hamacher of the University of Melbourne has now provided several pieces of supporting evidence that the collective memories of the Palawa people stretched back that far.

Even after much of Bass Strait was underwater, a landbridge allowed passage to the mainland. That ended by 12,000 years ago.

Image Credit: Hamacher et al./Journal of Archaeological Science

Besides the references to Tasmania’s isolation, Robinson also took down references to a bright star in the south that did not move, as part of a story that recounted the relationship between Moeherne and Droemerdeenne, star children of the Sun and Moon. He was clearly very puzzled by this, crossing out and interchanging the star children’s names.

For a star to not appear to move it needs to be close to a celestial pole. Currently, that’s the case for Polaris in the Northern Hemisphere, making it a precious asset for lost travelers throughout the Northern Hemisphere, but there is no bright equivalent near the South Celestial Pole.

However, Hamacher and co-authors have provided a plausible explanation: the story comes from a time when the star Canopus was much further south in the sky. Crucially, the time when the stories could have been true was around 12,000 years ago, making them very similar in age to the flooding of Bass Strait.

No bright star has been as close to the South Celestial Pole as Polaris is to the north for a very long time, but 12,000 years ago Canopus was close enough to do the job. Being the second brightest star in the sky, then and now, Canopus would also have stood out far more than Polaris does and appeared to move only marginally through the night. Despite Robinson’s confusion as to which stars the story relates to, Hamacher points out that if the other key figure reported was Sirius, the story almost perfectly describes the brightest stars at the time the Bass Strait flooded.

Although the precession of the Earth’s axis, the reason Canopus has moved by 25 degrees in the intervening time, was known to European scientists long before Robinson, there is no evidence he was aware of it. Therefore, it is very unlikely he adjusted the tales he was recording to make them fit.

In addition to Robinson’s account, Hamacher and co-authors also looked into the notes made by Francis and Anna Marie Cotton, Quakers who claim to have supported Palawa and recorded their stories. Historians treat these with great suspicion, both because the Cottons appear to have exaggerated how close they were to Palawa survivors – possibly inventing some fictitious sources – and because the original notes were lost in a housefire in 1959. A descendant, Jackson Cotton, reconstructed them in the 1960s, claiming to have read them so often he could remember every detail, but the reliability of his memories is questioned.

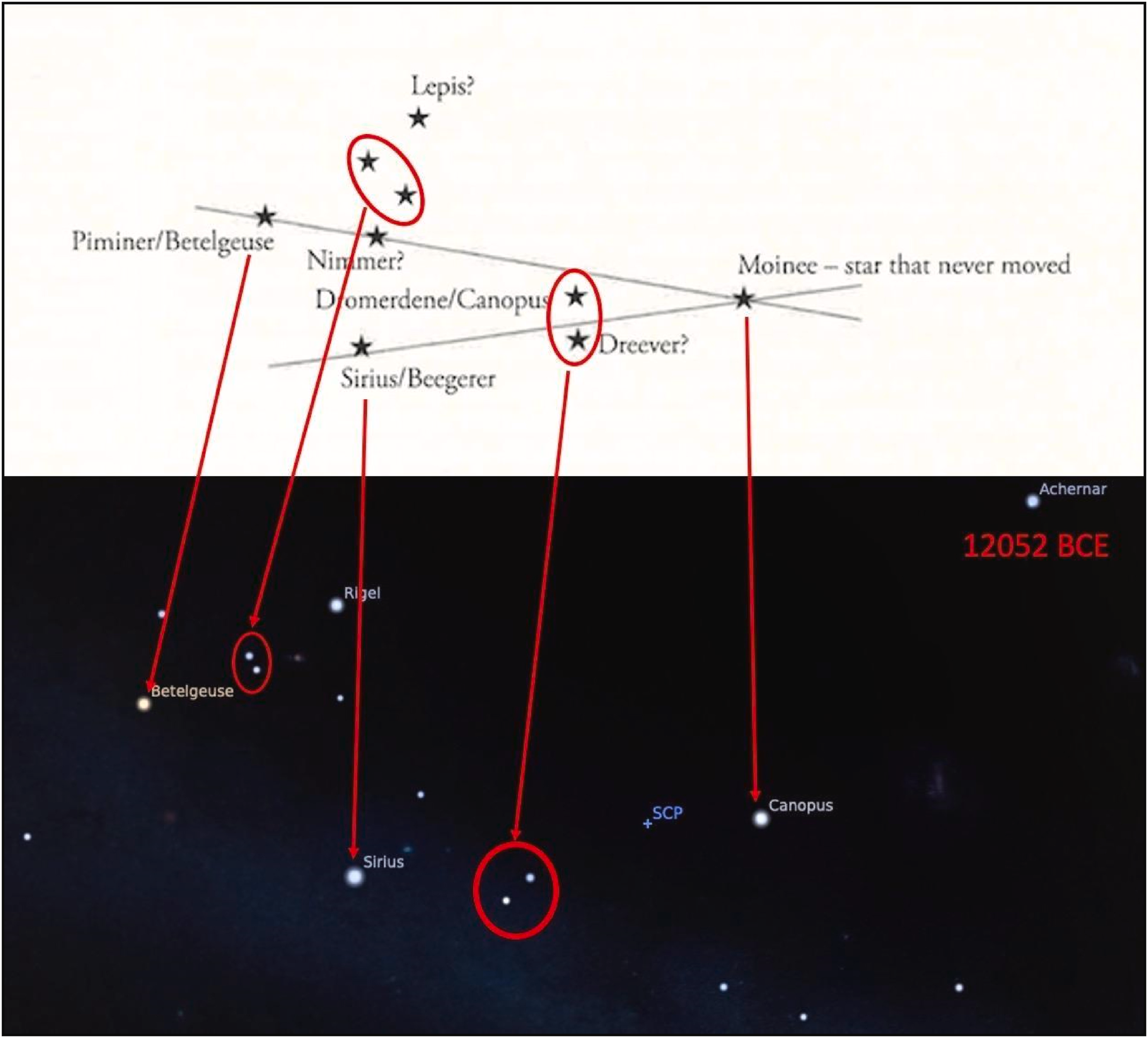

However, Jackson Cotton provides a star map that, while more detailed than what Robinson describes, is consistent with both Robinson’s and the positions of the brightest southern stars 12,000 years ago. While acknowledging the question marks over the Cottons’ accounts, Hamacher points out it would be doubtful the Cottons would have been aware of the stars’ ancient positions, making ancestral stories the most likely source for the map.

Top, star map drawn by Jackson Cotton based on his memories of one in his great grandparents’ diaries, which was supposedly initially drawn in sand by Indigenous friends. Bottom: the brightest stars in the sky 14,000 years ago.

Image credit: Hamacher et al/Journal of Archaeology. Top from Jackson Cotton, bottom Stellarium

According to Hamacher the flooding of Bass Strait was such a catastrophe for the Palawa it’s unsurprising it was transmitted in memory. Besides cutting the Palawa off from mainland Australia, it also probably cost them their best hunting grounds. “The inner part of Tasmania is not very hospitable,” Hamacher told IFLScience. “People were living on the land bridge and got pushed to Tasmania, which created all sorts of problems.” The population is believed to have crashed with the separation, and never fully recovered.

A southerly star, even one as bright as Canopus, doesn’t seem as obviously significant, but Hamacher told IFLScience, “It would have been an ideal navigation star, as Polaris (which Polynesian cultures call ‘the star that doesn’t move’) is. It would have been an accurate tool to find your way south, unlike now when you have to triangulate.”

Hamacher says he is not aware of stories from mainland Australia, or other southern continents for that matter, that recall a time when Canopus barely moved. However, he thinks this is as likely to reflect a failure of anthropologists to record these tales as them not having survived since it would have been just as useful a guide for other Southern Hemisphere peoples.

The Cotton diaries also include accounts of what appear to be icebergs floating past. The waters around Tasmania today are far too warm for such a sight. However, Tasmania’s mountains had glaciers not long before Bass Strait flooded, and these may have carved large blocks of ice into the island’s rivers. Hamacher told IFLScience he is not sure if the more extensive Antarctic sea ice of the period could also have led to icebergs within sight of Tasmania.

Even prior to Hamacher’s work, the idea that the accounts Robinson collected were real has been bolstered by evidence that accounts of other ancient floods have been passed on for impressive periods. For example, a volcanic eruption and rising seas isolating an island are both recorded in stories from different parts of Queensland.

It has been proposed the Gunditjmara people of Western Victoria’s stories of ancient giants refer to a volcanic eruption 37,000 years ago, but Hamacher described this to IFLScience as “Not very solid. They might have worked out what happened without witnessing it”. It has also been suggested that global references to the Pleiades as having seven members recalls a time 100,000 years ago when it was easier to distinguish Pleione from Atlas, but this relies even more heavily on guesswork.

Consequently, if Robinson and the Cottons’ records really record stories dating back 12,000 years they have a strong case to be the oldest surviving human tales.

The study is open access in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

[H/T Australian Geographic]

Source Link: At 12,000 Years Old, Tasmanian Indigenous Stories Could Be The World’s Oldest