As if Australia’s mammalian fauna was not already weird enough, they also glow under ultraviolet light. The reasons for this are still not understood, but scientists have improved our knowledge by studying the molecules responsible, and finding they differ among species.

Certain molecules absorb ultraviolet light and re-radiate it at wavelengths we can see. Consequently, when exposed to “black lights” (UV light sources with little or no visible light) anything with these molecules near the surface will produce an eerie glow, known as photoluminescence.

The fact that some mammals are photoluminescent has been known at least since 1911. However, the topic attracted little attention until 2019 when flying squirrels were revealed to glow bright pink under black lights. This set off a race to check other animals, particularly among museum creators with little else to do during the pandemic, and we learned how common it is.

In particular, platypuses, who with echidnas are only very distantly related to all other mammals, turn out to glow a mix of blues, greens, and purples. Either photoluminescence goes all the way back to the base of the mammal family tree, or it has evolved many times.

Linda Reinhold and colleagues at James Cook University investigated what was causing this glow using fur samples from animals killed by cars. They found several luminescent molecules in the fur of seven mammals native to northern Australia. Not all the mammals had the same molecules, giving them different colored glows; and one species, the coppery brushtail possum, turned out to have something particularly intriguing going on.

“The fur of the Australian northern long-nosed and northern brown bandicoots photoluminesces strongly, displaying pink, yellow, blue and/or white colours,” Reinhold said in a statement.

Long-nosed bandicoots are marsupials, yet they have a similar color under UV light to placental flying squirrels.

Image courtesy of Linda Reinhold

The team found the molecule porphyrin causes the fur of bandicoots, quolls, and possums to glow bright pink under black light. Meanwhile metabolites of tryptophan produce a blue shade. Sometimes the color an animal glows depends on the wavelength of UV used.

In the process, the researchers also discovered that coppery brushtail possum fur contains an unexpected molecule which is not luminescent, but produces a purple color similar to the molecule indigo used for millennia, including to dye jeans. Once again, curiosity-driven science finds something besides what the researchers were looking for, although whether this will prove as significant as some past examples remains to be seen. “This piece of chemistry on possums also gives renewed hope to solving the cause of the puzzling fur colouration of species such as the purple-necked rock-wallaby,” Reinhold said.

The most puzzling aspect of all this glow is why? It’s hard to see an evolutionary benefit for glowing like this for most species (although a few might use the capacity to attract mates). Animals in the wild don’t encounter UV lights at night, and during the day the glow is overwhelmed by ordinary colors. However, there can be a delay, where molecules exposed to UV light from the Sun keep on glowing after sunset or moving somewhere dark.

All this research was published in dusty old black and white journals and no one paid attention.

Linda Reinhold

There’s a cost to making any molecule, even if it might be small, and predators might be expected to develop the capacity to spot even the faintest glow at dusk. However, in a previous study Reinhold found nocturnal animals don’t seem to respond to it.

However, Reinhold told IFLScience an evolutionary driver may not exist. “Every surface must either absorb, reflect or photoluminesce,” she said. “All these molecules are floating around inside our bodies with functional purposes.” They’re never exposed to UV light there, nor is there anyone to see them.

Other aspects of these molecules are very important, however. One of the glowing molecules is a precursor for hemoglobin, vital to vertebrate life, while tryptophan performs a wide range of functions, including producing serotonin to keep our mood positive. It could be pure coincidence that when something so useful gets into fur it produces pretty colors under conditions animals seldom encounter.

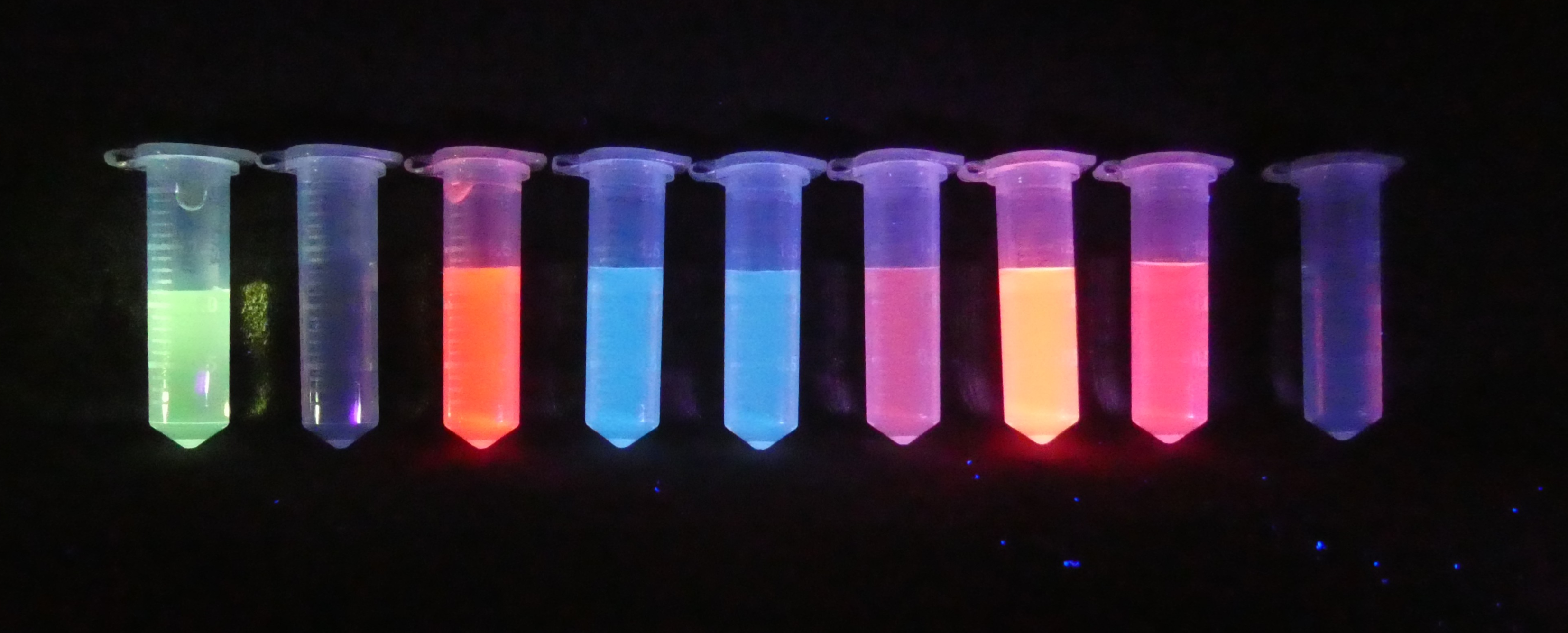

Separated out, the molecules that cause coppery brushtail possums to glow reveal quite a mix of colors.

Image courtesy of Linda Reinhold

In fact, the vast majority of mammals are photoluminescent, including humans with lighter colored hair. Reinhold explained that melanin masks the effect where fur or hair is dark enough. Nevertheless, the differences in color between species may reflect something important.

One factor Reinhold told IFLScience deserves further investigation is the coppery brushtail possum’s indigo shade. This seems to vary within the species, and Reinhold said, “We think it’s in the plants they eat.” We know some animals, such as flamingos, take on the color of their diet, and this discovery could help us track some animals’ diets.

Although photoluminescent animals have been known for a long time, most of the world only discovered them in the last six years. Reinhold attributed this to “color photography and the Internet”. She told IFLScience, “All this research was published in dusty old black and white journals and no one paid attention.” Now that images can be shared on social media public interest has spiked, and some scientists have been encouraged to take a deeper look.

The study is published open access in PLOS One.

Source Link: Australian Mammals’ Black Light Glow Is Caused By Several Different Molecules