Optical illusions work by challenging our brains to break out of their usual pattern of viewing the world, reconfiguring the way they process, predict and analyze visual stimuli. This requires intricate communication and feedback between different brain regions, and new research indicates that this process may be altered in autistic children.

“When we view an object or picture, our brains use processes that consider our experience and contextual information to help anticipate sensory inputs, address ambiguity, and fill in the missing information,” explained study author Emily Knight in a statement. However, previous research has demonstrated that individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) process these sensory inputs in an atypical manner.

For example, last year Knight authored a study which showed that children diagnosed with ASD didn’t automatically process human body language in the same way as kids without autism. Noting this delay in unconscious processing, the researchers began to suspect that feedback between higher-order brain regions and primary sensory regions may be disrupted in those with ASD.

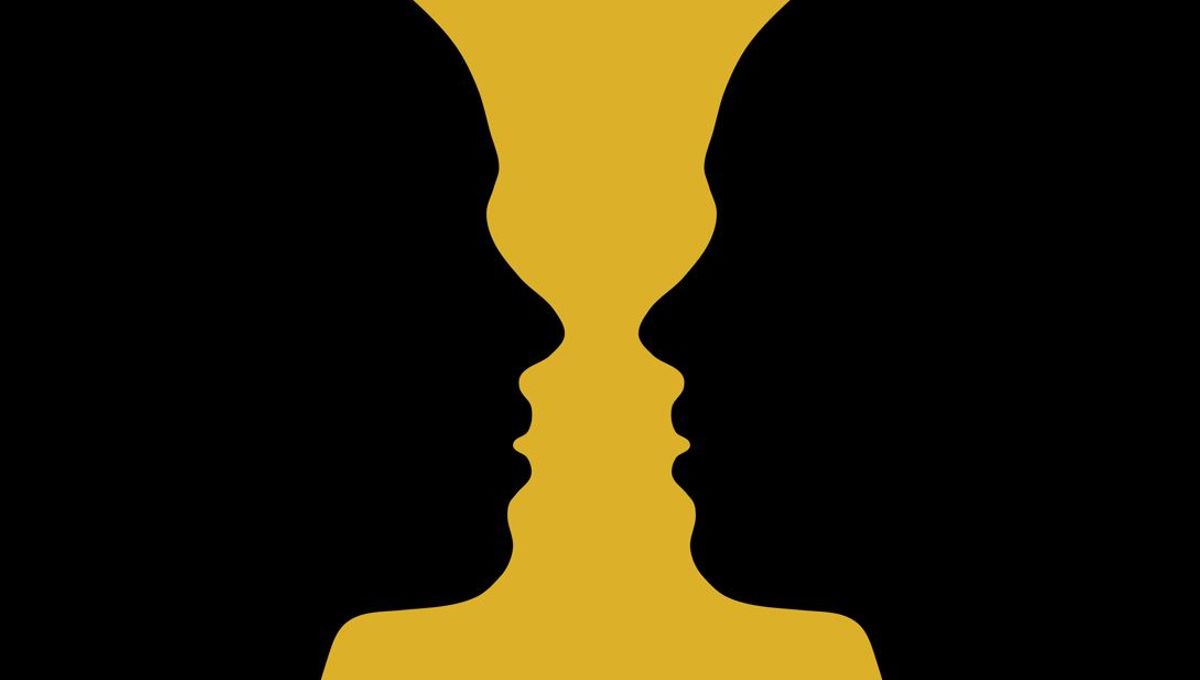

Optical illusions provide the perfect tool with which to test this assumption, and Knight and her colleagues used the famous Kanizsa figure trick to explore their hypothesis. Named after Italian psychologist Gaetano Kanizsa, the illusion involves multiple shapes arranged in such a way as to create the contours of another image, such as two human faces that appear to be looking at one another, leaving the form of a vase in the empty space between them.

The study authors recruited 60 children – including 29 with ASD – to take part in an experiment in which they were asked to focus on a dot in the middle of a screen while Kanizsa figures appeared in the background. By not focusing on these illusions directly, participants viewed them passively rather than actively, giving the researchers a chance to study their automatic brain activity in response to these odd figures.

Using electroencephalography (EEG) to record the kids’ brainwave activity, the study authors noticed that those with ASD were slower at processing the Kanisza shapes than non-autistic children. “This tells us that these children may not be able to do the same predicting and filling in of missing visual information as their peers,” says Knight.

Based on this observation, the researchers state that those with autism appear to display deficits in “visual feedback processing”, meaning the communication between sensory input regions and those involved in analyzing these signals may be less efficient in autistic children.

“Continuing to use these neuroscientific tools, we hope to understand better how people with autism see the world so that we can find new ways to support children and adults on the autism spectrum.”

The study appears in The Journal of Neuroscience.

Source Link: Autistic Children "See" This Optical Illusion In A Unique Way