A UK regulator has confirmed that a small number of babies with DNA from three different people have been born in the country. The technique to create “three-parent” embryos became legally permissible several years ago, but it’s only now that information has been obtained establishing that the procedure has been successfully used in the UK.

What’s the latest news?

An investigation by the Guardian newspaper has revealed that a handful of babies – fewer than five – have been born as a result of mitochondrial donation treatment (MDT), as of April 2023.

The UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), the independent regulator of fertility treatment and human embryo research, has approved at least 30 individual cases for MDT, but did not release a precise figure for the number of successful live births, nor any further details, to avoid “the identification of a person to whom the HFEA owes a duty of confidentiality.”

The UK government legalized MDT back in 2015, with the world-first formal approval for the use of the technique coming the following year. Only one clinic, the Newcastle Fertility Centre, is licensed to perform the procedure. It’s thought that the program has been hampered by restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, perhaps meaning that fewer couples than expected have so far been able to come forward for treatment.

These babies are not the first to have been born using this technique, however. The first was born in early 2016 in Mexico, where doctors from the US assisted a Jordanian couple to undergo in-vitro fertilization (IVF) following MDT.

Why use DNA from three people?

MDT was developed to treat a specific type of genetic disorder called mitochondrial disease. Functioning mitochondria are essential to supply the body’s cells with the energy they need, and mutations in mitochondrial DNA can affect this complex system in many ways, causing a huge range of symptoms.

Mitochondrial DNA is inherited via the mother. The aim of MDT is to swap out the genetic material from an embryo’s biological parents into a new donor egg cell, containing healthy mitochondria.

It’s difficult to determine exactly how prevalent mitochondrial mutations are, but it’s been suggested that up to 1 in 250 otherwise healthy individuals could carry low levels of pathogenic mutations. The US-based United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation estimates that every 30 minutes, a child is born who will go on to develop mitochondrial disease by the age of 10.

Since babies inherit all of their mitochondria from their mother, and there’s no way to predict how much each individual child will be affected if an at-risk woman conceives naturally, preventing faulty mitochondrial genes from being passed on altogether is an attractive treatment strategy.

How does the procedure work?

Two techniques are approved for use in the UK, and they broadly work in the same way.

In both cases, the aim is to produce embryos containing a full set of chromosomes from the biological parents – about 99.8 percent of the total genetic material – as well as a small number of mitochondrial genes from a donor egg cell to replace the mutated mitochondrial DNA from the mother.

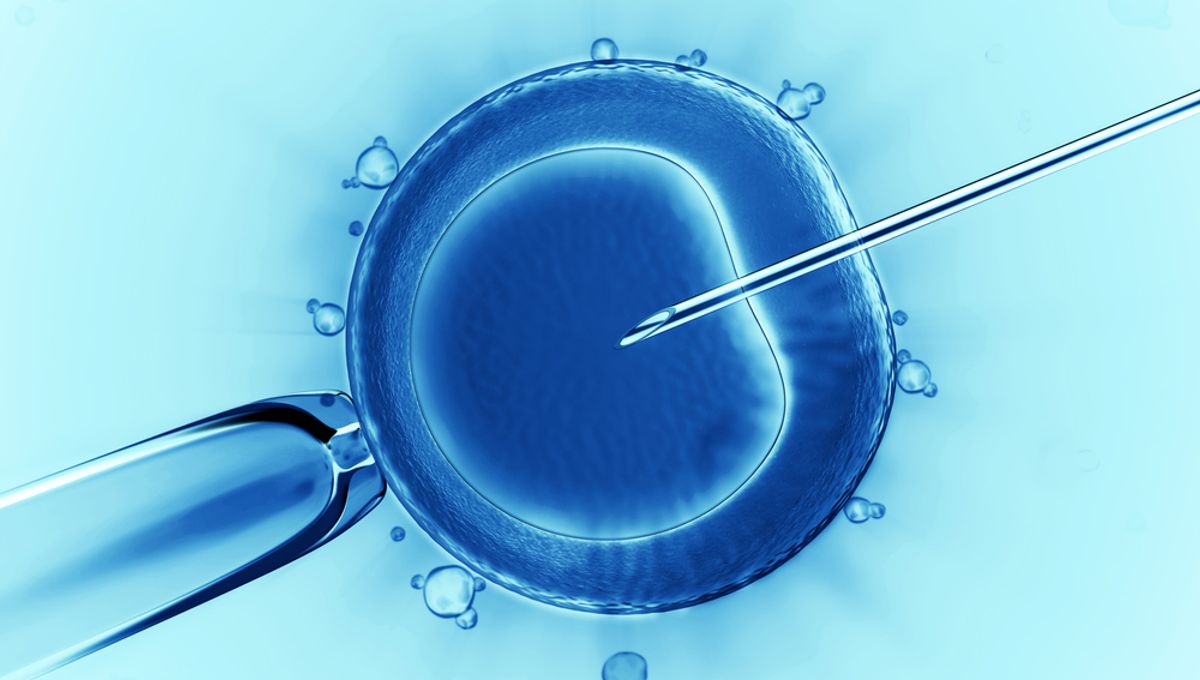

The nuclear genetic material of the mother’s egg cell may be transferred into a donor egg cell that has had its own genetic material removed before this egg cell is fertilized using the father’s sperm. This is called maternal spindle transfer (MST).

Alternatively, both the mother’s and the donor’s eggs may be fertilized with the father’s sperm first, before the nuclei from the mother’s cells are swapped into the donor cells. This is called pronuclear transfer (PNT).

A child born from MDT does not have the right to any identifying information about the egg donor, nor would the donor have any parental rights or responsibilities towards the child. From the age of 16, a child will have the right to some non-identifying information, such as the results from the donor’s medical screening tests.

Where do we go from here?

It’s still early days for this technology, and like any medical procedure, MDT is not without risk.

“So far, the clinical experience with MRT has been encouraging, but the number of reported cases is far too small to draw any definitive conclusions about the safety or efficacy,” Dagan Wells, a professor of reproductive genetics at the University of Oxford who has carried out research into MDT, told the Guardian.

For example, it’s impossible to avoid a minuscule number of mitochondria being transferred to the donor egg along with the mother’s genetic material, and in rare cases, these may multiply while the embryo is developing in the womb – so-called “reversal”.

“The reason why reversal is seen in the cells of some children born following [MDT] procedures, but not in others, is not fully understood,” said Wells. “Long-term follow-up of the children born is essential.”

While this latest news has confirmed what many had already suspected – that successful births following MDT have already happened in the UK – experts have stressed the need to respect the privacy of the families involved, as well as waiting for the publication of any peer-reviewed data.

“I am sure that [details] will be made available, probably in a peer-reviewed scientific publication and hopefully in the near future,” commented Professor Robin Lovell-Badge of the Francis Crick Institute. “The Newcastle team involved in carrying out the procedures are cautious and will have wanted to include at least some follow-up data on the babies, while also protecting the privacy of the families.”

This was echoed by Sarah Norcross, director of the charity PET: “The purpose of this technology is to give people a way of avoiding the transmission of debilitating mitochondrial disease to their children. Given the toll that such disease is likely to have taken on the first families who have made use of mitochondrial donation, it is especially important that the privacy of these families is respected.”

All “explainer” articles are confirmed by fact checkers to be correct at time of publishing. Text, images, and links may be edited, removed, or added to at a later date to keep information current.

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of qualified health providers with questions you may have regarding medical conditions.

Source Link: Babies With Genes From 3 People Born In The UK – What’s Going On?