A protein produced by certain bacteria can not only extract the elements neodymium and dysprosium from the ore in which they are found, but separate them from each other. With demand for these metals growing exponentially, thanks to their role in wind turbines and electric vehicles adding to existing demand from smartphones, the discovery could be a game-changer in the decarbonization race.

Despite their name, rare earth elements are not actually all that rare. Neodymium, for example, is the 27th most common element in the Earth’s crust, far ahead of mercury (67th) and gold (75th). The amount of neodymium that needs to be added to iron to make spectacularly powerful magnets isn’t very large, so there’s no danger of the world running out. Unfortunately, however, extracting and refining these useful elements is a messy and expensive business.

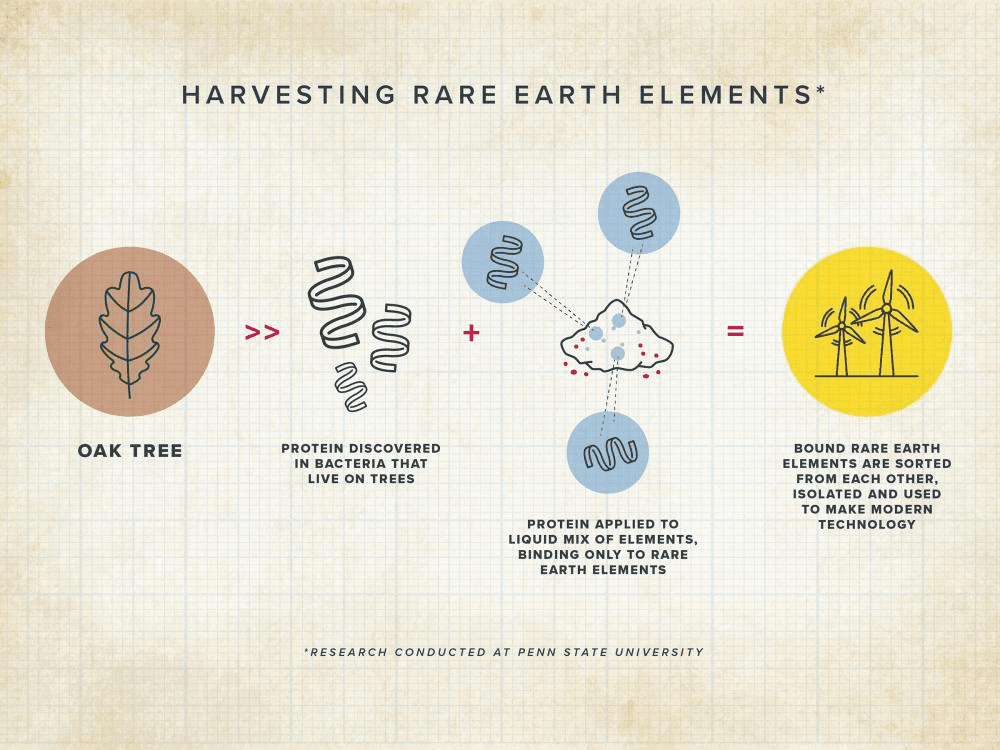

A technology outlined in Nature could change that. Scientists at Penn State University showed that a specific form of the protein lanmodulin can distinguish exceptionally similar elements.

“Biology manages to differentiate rare earths from all the other metals out there – and now, we can see how it even differentiates between the rare earths it finds useful and the ones it doesn’t,” said Dr Joseph Cotruvo in a statement. “We’re showing how we can adapt these approaches for rare earth recovery and separation.”

The challenge in mining lanthanides, which include most of the rare earth elements, is that they never appear in pure form. Besides being mixed with common elements, lanthanides exist in nature together, and the similar chemistry that deposits them in the same place also impedes separation.

“There is getting them out of the rock, which is one part of the problem, but one for which many solutions exist,” Cotruvo said. “But you run into a second problem once they are out, because you need to separate multiple rare earths from one another. This is the biggest and most interesting challenge, discriminating between the individual rare earths, because they are so alike.”

Existing processes involve repetitive steps, sometimes hundreds of them, each requiring toxic chemicals.

Six years ago, Cotruvo and colleagues isolated a protein they called lanmodulin from methylotroph bacteria, which they found binds more than 100 million times as strongly to lanthanides as more common metals.

While potentially useful, this doesn’t address what Cotruvo noted is the hardest part of the problem, breaking up a mix of 15 elements.

However, lanmodulin turns out to be a family of hundreds of similar-looking proteins produced by different bacteria. The Hansschlegelia quercus bacterium found in English oak buds can differentiate between lanthanides, as well as separating all of them from other metals.

When binding to a light lanthanide, Hansschlegelia’s lanmodulin forms sets of two identical molecules (dimers), but with heavier members of the group it goes solo.

How lanmodulin from an arborial bacteria could open a path to cleaner energy generation.

“This was surprising because these metals are very similar in size,” Cotruvo said. “This protein has the ability to differentiate at a scale that is unimaginable to most of us – a few trillionths of a meter, a difference that is less than a tenth of the diameter of an atom.” How the bacteria benefit is unclear.

Attaching the protein to beads without involving bacteria, the team have demonstrated the capacity of the protein to separate neodymium and dysprosium, the two lanthanides used in permanent batteries, without needing organic solvents or high temperatures.

Distinguishing between one half of the lanthanides and the other might cut a few stages out of the separation process, but still leaves plenty of work to do. Neodymium and dysprosium are six spots apart on the periodic table. What is really needed is a version that distinguishes each from their immediate neighbors, which are only a few trillionths of a meter different in size.

Using X-ray crystallography, the team found a single amino acid that is crucial to the lanmodulin’s differential treatment of elements.

“With further optimization of this phenomenon…efficient separation of rare earths that are right next to each other on the periodic table may be within reach,” Cotruvo said.

Along with the environmental and economic benefits, the work could have considerable geopolitical significance. China dominates rare earth production, not because other countries lack deposits, but because others haven’t tolerated the pollution currently involved in their processing. This dominance is now alarming the US and allies, making cleaner techniques much desired.

The study is published in Nature.

Source Link: Bacteria Are Better At Mining Rare Earth Elements Than We Are