Bright meteors are sometimes followed by two effects, known respectively as trails and trains. Trails are well understood, but trains are a different matter. Most trains disappear within seconds, but a rare few can last for up to an hour. Advances in photography have allowed scientists to study this phenomenon is much greater depth, proving persistent trains are much more common than previously thought, and are most often associated with debris left by one comet family.

A bright meteor can lift the spirits of even the most experienced sky-gazer. We recommend Northern Hemisphere residents take the opportunity to witness the Perseid meteor shower that is currently raising meteor rates significantly if they can.

What makes meteors so exciting is not just the blazing flash of light that always takes one by surprise, but the variation in brightness, speed and color. Bright meteors sometimes have the added feature of a train that stays in the sky after the original flash has gone. The International Astronomical Union defines a trains as “Light or ionization left along the trajectory of the meteor after the meteor has passed.”

Most trains last tens of second at most. Persistent trains, however, can last up to an hour.

Like the rare meteor sounds, persistent trains have proven hard for scientists to explain, but are thought to relate to iron from the meteor combining with ozone to produce iron oxide and oxygen. Other metals in the meteorite probably also play a part. The energy of the reaction can apparently sustain light long after the meteor has passed.

The first scientific investigation of meteor trains was conducted more than a century ago, but interest in persistent trains shot up after the Leonid meteor storms of 1999-2002. Even among those events numerous awe-inspiring features, the persistence of some trains – reportedly more common than usual – aroused curiosity.

Astronomers have established widefield cameras to try to track the trains of potential meteorites to the landing sites, with considerable success. University of New Mexico PhD student Logan Cordonnier and colleagues deployed similar technology in his home state in the form of the Widefield Persistent Train camera. These were checked against records in the Global Meteor Network database, which provides information about bright events, sometimes revealing the source and composition of the space dust responsible, and the train’s altitude.

Over almost two years, 4,726 meteors were captured by both, of which 636 produced trains. Persistent trains were rarer, seen from one meteor in 19, but far more common than previously thought. Analysis revealed slower meteors are even more likely to produce persistent trains than fast ones, contradicting previous studies. The authors attribute this to the fact that slower meteors are more likely to survive low enough to reach an altitude below 93 kilometers (58 miles) above Earth’s surface – the cutoff point they calculated – while faster ones break up first.

More surprisingly, persistent trains are common among fainter meteors, although trains from brighter meteors do last longer. Of all the meteor showers the team observed, the little-known Andromedids had the highest proportion of trains produced. The Andromedids occur in late November and attract little attention because their meteors are rare and generally faint and slow, although some years in the late 19th century saw impressive numbers and 2021 marked a partial return to form.

All meteor showers, bar one, are caused by debris from comets. The Andromedids are from the former comet 3D/Biela. Like the source of other showers with high train production this was a Jupiter Family Comet, meaning it has an orbit of less than 20 years, making it frequently influenced by Jupiter’s gravity.

Why Jupiter Family Comets produce more trains remains unknown, but it’s a good tip for astronomical train spotters. The authors also suspect that meteors from comets that broke up recently are more likely to have lasting trains.

Trains start with an initial afterglow, whose colors reveal the presence of metals separated from the meteorite in passage through the atmosphere and heated until they emit light. As these elements cool, they recombine with electrons in the atmosphere, generating a recombination phase.

Both processes are well understood, but they last tens of seconds at the most. It is the third phase, more seldom seen, that has been more puzzling.

The authors of the new study acknowledge that the previous theories were based on observations of the Leonids. Since these are some of the fastest meteors we encounter, it’s possible such explanations were accurate for that sample, but they are inconsistent with the slower examples seen here.

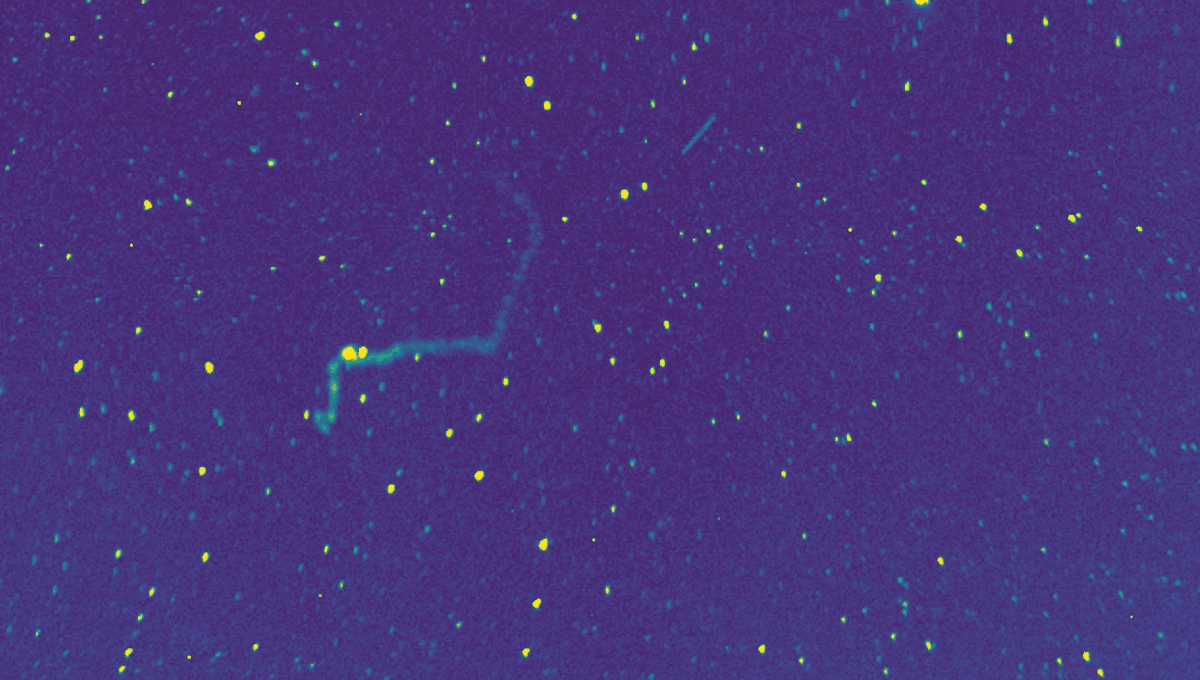

Trains are affected by winds in the upper atmosphere and can be turned into spirals or even knots under the right circumstances.

Persistent trains could provide a way to probe the ozone layer’s atmospheric chemistry. Cordonnier told Science News this area is frustrating: “It’s too high in the atmosphere for weather balloons, and it’s too low for satellites to take direct measurements. It’s a difficult region to probe.” Watching meteor trains could be the answer.

Trails, by contrast are from smoke left behind as the meteor burned up being lit up by scattered sunlight, shortly after sunset or before sunrise.

The study is open access in the Journal of Geophysical Research – Space Physics.

Source Link: Beautiful, Long-Lasting Sky Trains Left By Meteors Occur More Often Than We Thought