In 1979, a deadly pathogen really did leak out from a lab, killing at least 66 people and many animals nearby. Sometimes known as the “biological Chernobyl”, the disaster was covered up by the Soviet authorities, with the truth only emerging to the rest of the world in the 1990s.

According to official accounts by the Soviet Union, in 1979 there was an outbreak of intestinal, food-borne anthrax in the city of Sverdlovsk. Reports of an epidemic in Sverdlovsk didn’t make their way into the western press until 1980. Later that year, articles about an outbreak were published in Soviet medical and veterinary journals, attributing it to contaminated meat from diseased animals.

But, as was obvious to one epidemiologist, Viktor Romanenko, at the time: The cases did not fit the pattern and timing you’d expect from food-borne anthrax. It was plain to Romanenko, who was made to play a part in the cover-up, that the anthrax was airborne.

Towards the end of the Soviet Union, articles began to appear in the Russian media questioning whether the anthrax could have been food-borne, and whether a military microbiology facility in the city could have been involved in the release.

Though medical files of infected patients had been destroyed during the cover-up, a team of investigators was able to secure pathologist notes from the autopsies of 42 people, giving their age, when their symptoms started, when they were admitted, and when they died. As well as this, they had access to 110 hospital records showing addresses and names of patients screened for anthrax poisoning, 48 of whom then died of the disease.

Using these records and interviews with survivors and surviving family members, the team placed the probable place at time of infection for each patient over a map of the city. It created an almost-comical conical shape, emitting from the lab itself and spreading south east.

The team, publishing their research in Science, put the outbreak down to a single release of an aerosol anthrax pathogen.

“We conclude that the outbreak resulted from the windborne spread of an aerosol of anthrax pathogen, that the source was at the military microbiology facility, and that the escape of pathogen occurred during the day on Monday, 2 April,” the team wrote in their discussion.

“The narrowness of the zone of human and animal anthrax and the infrequency of northerly winds parallel to the zone after 2 April suggest that most or all infections resulted from the escape of anthrax pathogen on that day.”

The Soviets, though banned like all others who signed up to the Biological Weapons Convention of 1972, continued the production of anthrax that could be weaponized. President Boris Yeltsin later admitted that the military was to blame for the incident, which he helped to cover up as the top official in the region.

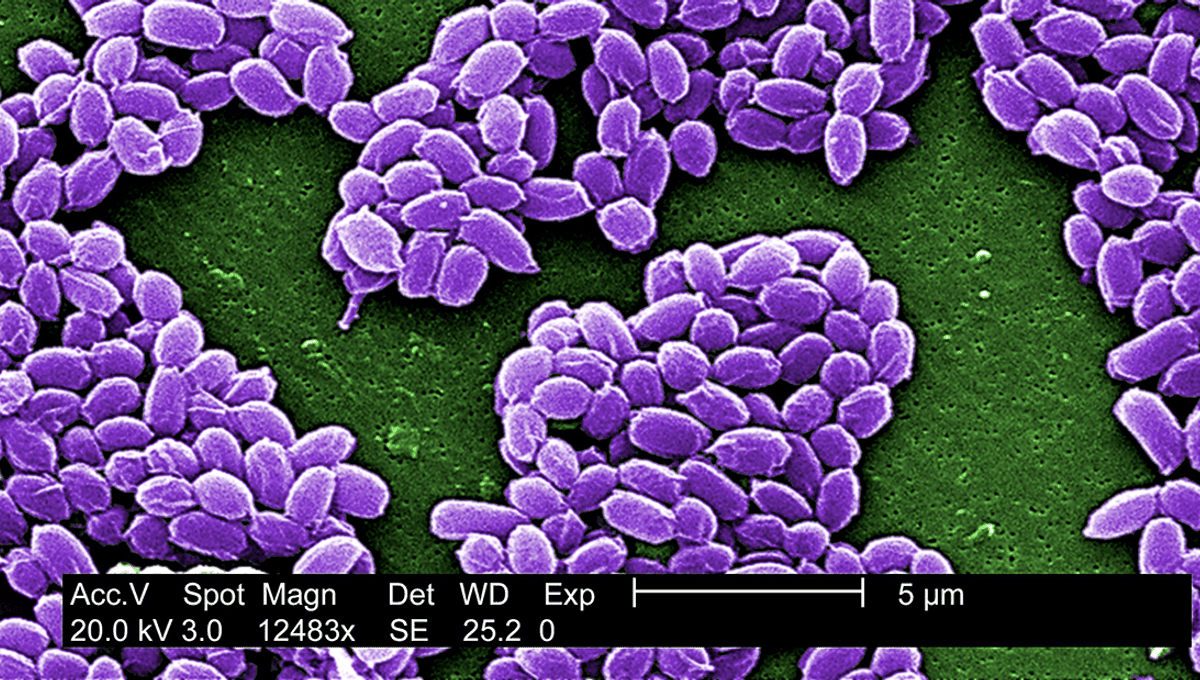

In 2016, another team sequenced the DNA of a strain taken from the bodies of two anthrax victims. Mapping its genome, they determined that it was closely related to strains that the Soviets used as vaccine strains. There had been questions whether the Soviets had attempted to manipulate the pathogen in order to make it deadlier.

“While it is known that Soviet scientists had genetically manipulated Bacillus anthracis, with the potential to evade vaccine prophylaxis and antibiotic therapeutics,” the team concluded, “there was no genomic evidence of this from the Sverdlovsk production strain genome.”

Weaponized or not, the strain was deadly enough, given that it was likely the deadliest outbreak of inhalation anthrax in humans in history.

Source Link: "Biological Chernobyl": When A Deadly Infectious Disease Broke Out From A Soviet Lab In 1979