The further we peer back toward the Big Bang, the more our theories run into trouble with observations. This is happening a lot right now with JWST, but ground-based telescopes are getting in on the act, including the discovery of a galaxy named COS-87259, found through the COSMOS search and confirmed by the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA). We’re seeing COS-87259 as it was just 750 million years after the universe burst into action – about 5 percent of its current age.

One notable feature of COS-87259 is its astonishing rate of star formation, a thousand times that of the Milky Way.

The light of so many hot young stars allows us to see COS-87259 despite its immense distance, but another source of luminosity is the large and growing supermassive black hole at its core, estimated to be as massive as 1.6 billion Suns. It is this that is the focus of a paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The authors think COS-87259’s active galactic nucleus could be key to understanding the evolution of the immensely massive black hole at the heart of most galaxies.

Supermassive black holes from the early universe have been seen for decades – indeed for a long time, they were the only thing we could see that far back. Known as quasars, they are black holes that are actively feeding on surrounding material and producing jets largely unhidden by dust. This combination makes them visible over immense distances, yet even quasars are seldom found at distances as great as COS-87259. We only average one discovery for 3,000 square degrees.

COS-87259, on the other hand, is very obscured by dust (about 2 billion solar masses of it) and consequently wouldn’t have been detectable with most prior sky surveys. Consequently, the interesting thing to astronomers is how quickly we found it once we had the capacity. The COSMOS search only studied an area of about 1.5 deg2, seven times the apparent size of the full Moon, and turned up COS-87259. Either objects like this are actually quite common – at least compared to quasars at the same distance – or astronomers got exceptionally lucky in their choice of where to look first.

At an estimated 170 billion solar masses, COS-87259 (around a seventh of the Milky Way) has assembled remarkably fast in such a short time. The way a few galaxies got so big so fast is becoming quite a problem for cosmology.

“These results suggest that very early supermassive black holes were often heavily obscured by dust, perhaps as a consequence of the intense star formation activity in their host galaxies,” said Dr Ryan Endsley of the University of Texas at Austin in a statement. “This is something others have been predicting for a few years now, and it’s really nice to see the first direct observational evidence supporting this scenario.”

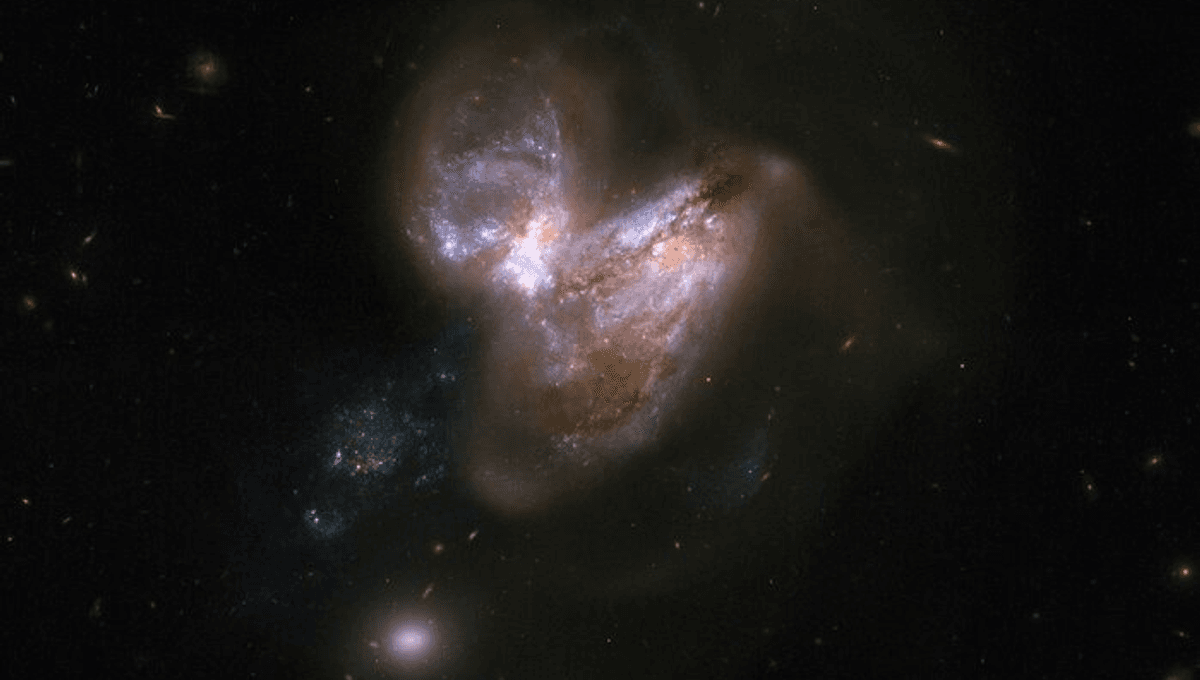

The authors think what we are seeing is an early version of Arp 299, a pair of galaxies whose collision has set off an intense burst of star formation and created numerous “ultra-luminous X-ray sources”.

“While nobody expected to find this kind of object in the very early Universe, its discovery takes a step towards building a much better understanding of how billion solar mass black holes were able to form so early on in the lifetime of the Universe, as well how the most massive galaxies first evolved,” Endsley said.

Surveys of much larger areas of the sky capable of detecting objects like this are coming and should tell us whether they were indeed common in the early universe or if finding COS-87259 was a fluke.

The paper is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Source Link: Bright But Obscured Supermassive Early Universe Black Hole Could Represent New Type