After 130 years of absence, Tulare Lake briefly remerged from the San Joaquin Valley last year. Now, however, the indecisive “phantom lake” has disappeared into obscurity once again, leaving an uncertain future for the residents and farmers of California’s Central Valley.

Tulare Lake was once the largest lake west of the Mississippi River, holding a vast quality of water stretching over 160 kilometers (100 miles) long and 48 kilometers (30 miles) wide.

Known as Pa’ashi to the Indigenous Tachi Yokut tribe, it had served as a traditional hunting and fishing site for centuries. Things drastically changed in the 19th century when the state of California carried out a series of land grabs and put the region under private ownership in the 1850s and ‘60s.

The lake was drained of water and turned into arable farmland. By the 1890s, it had totally disappeared. Its waters briefly reappeared a handful of times over the past century, gaining a reputation of being a “ghost lake”, but Tulare Lake was effectively considered done and dusted.

Then, in early spring 2023, it returned once again in the wake of weather events in southern California. The body of water is fed by the Sierra Nevada mountains, which were struck by several snowstorms in the winter of 2023, causing a flood of water to pour into the San Joaquin Valley.

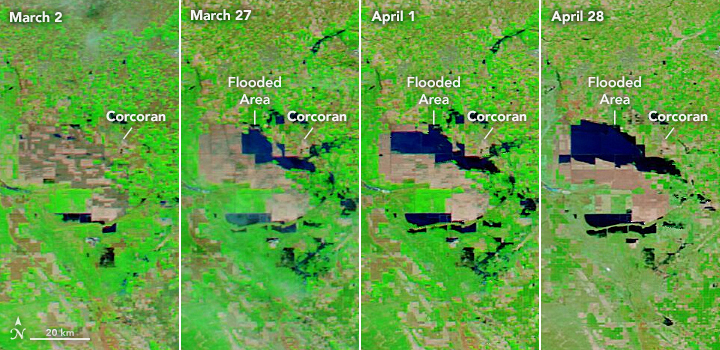

The rebirth of Tulare Lake seen in satellite images between March 2 to April 28, 2023

Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview

Its rebirth was both a blessing and a curse. While the rising waters destroyed swathes of farmland and property, it also saw the return of native wildlife, plus the Tachi Yokut tribe regained their ancestral lake.

“Most of the news coverage about this time talked about it as catastrophic flooding. And I don’t want to disregard the personal and property losses that people experienced, but what was not talked about so much is that it wasn’t only an experience of loss, it was also an experience of resurgence,” Vivian Underhill, formerly a postdoctoral research fellow at Northeastern University with the Social Science and Environmental Health Research Institute, said in a statement to Northeastern Global News.

“The return of the lake has been just an incredibly powerful and spiritual experience [for the Tachi Yokuts]. They’ve been holding ceremonies on the side of the lake. They’ve been able to practice their traditional hunting and fishing practices again,” Underhill says.

In early February, Underhill predicted the lake would remain here for at least two years – but within weeks it had almost disappeared.

“There’s no lake anymore. There’s some wet ground but nothing major,” Doug Verboon, Kings County Supervisor and farmer, told the San Francisco Chronicle.

While it’s goodbye for now, scientists at Northeastern University believe the lake is likely to make more reappearances in the future as climate change will continue to drive intense weather over the Sierra Nevada mountains and fuel flooding in the downstream region.

“This landscape has always been one of lakes and wetlands, and our current irrigated agriculture is just a century-long blip in this larger geologic history,” Underhill explained.

“This was not actually a flood. This is a lake returning.”

Source Link: California's Ghost Lake Reappears, Then Vanishes Once Again